Nightmares and night terrors (also known as sleep terrors) are both part of a group of sleep disorders referred to as parasomnias. Parasomnias can be categorized by the presence of undesirable experiences occurring during sleep or during sleep-wake transitions.

Image Credit: Rawpixel.com / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Rawpixel.com / Shutterstock.com

They may include sleepwalking (somnambulism), bed-wetting (sleep enuresis) or sleep talking (somniloquy). Although similar and often confused, there are key differences that differentiate the two.

What are nightmares?

Nightmares are coherent and vividly realistic dreams that become increasingly disturbing as they progress and result in waking from sleep. Nightmares commonly involve impending danger or distressing themes and provoke emotions such as fear, embarrassment or anxiety upon waking.

Nightmares are common and affect people across the lifespan, with 50 – 85% of adults reporting occasional nightmares. However, they are particularly prevalent in childhood, with prevalence reaching a peak between the ages of 5-10 years.

Whilst it is usual to experience intermittent nightmares, a small proportion of people experience chronic and recurrent nightmares which lead to insufficient sleep, causing distress and impairment. This is referred to as nightmare disorder and affects between 2-7% of children and approximately 4% of adults.

Although there is a lack of consensus concerning the cause of nightmares, several factors increase their risk and include:

- Some groups of medications including antidepressants and treatments for Parkinson’s disease;

- Another comorbid medical, psychiatric or sleep condition;

- Substance abuse or misuse.

What are night terrors?

Night terrors are episodes of screaming and agitated movement such as flailing or thrashing, accompanied by intense fear. They typically last between seconds and a few minutes and begin whilst still asleep.

A person who experiences a night terror may be mobile, leading to episodes of sleepwalking, and provoke aggressive behavior if restrained. Upon waking, the person may be confused, disoriented unable to recall the night terror episode when fully awake.

Although distressing to observe, night terrors are relatively common in young children with an estimated prevalence between 1-6%, the vast majority of whom will cease from episodes by adolescence. Children with a family history of night terrors are at a higher risk suggesting a genetic component to the disorder, and pre-existing medical conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea causing fragmented sleep are also an identified risk factor.

How do nightmares and night terrors differ?

Although both nightmares and night terrors are frightening and can cause sleep disturbances, they are not synonymous conditions. The key difference between the two lies in when they occur during the sleep cycle.

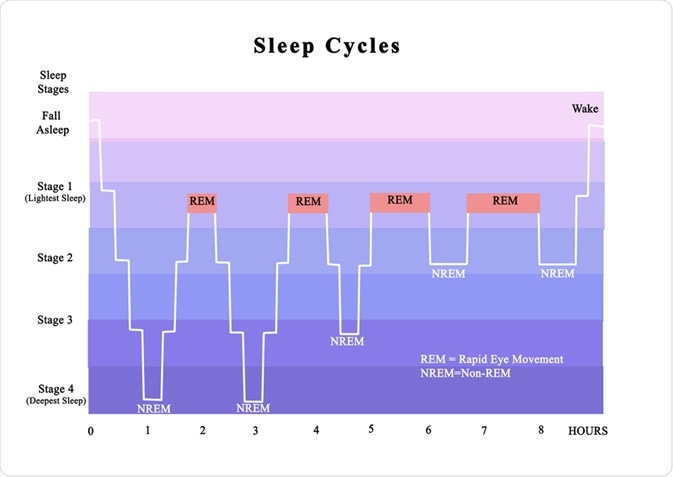

Sleep states are classified as either rapid eye movement sleep (REM) or non-REM (NREM) states. NREM sleep has four stages; transition from waking to sleep (Stage 1), light sleep (stage 2) and deep sleep (stages 3 and 4). During NREM sleep, respiration and blood flow decrease whilst muscle tone is akin to during wakefulness.

The fifth stage, REM sleep is characterized by random and rapid movement of the eyes, a propensity to report dreams and REM atonia (a state of temporary paralysis of the arms and legs). REM sleep occurs approximately 90 minutes after first falling asleep. A healthy sleep cycle will transition between these states throughout the night.

Parasomnias are also classified into NREM and REM parasomnias. Whilst nightmares occur during REM (dream) sleep, night terrors occur during NREM (usually stage 3) sleep. As a result, they differ in several ways:

- Confusion: Upon waking after a night terror people are generally confused and disoriented. After a nightmare, people orient themselves on waking.

- Amnesia: nightmares occur in dream states and arouse wakening. As such, they are usually remembered. Night terror episodes are not recalled after awakening.

- Degree of fear: during a night terror, a sufferer will appear terrified. Nightmares, although upsetting provoke less intense fear.

- Movement: REM sleep is accompanied by REM atonia; during a nightmare, the limbs are paralyzed. Movement during night terrors is not restricted and often co-occurs with sleepwalking.

- Timing: nightmares typically occur later at night when the brain reaches the REM stage of the sleep cycle. Night terrors by contrast, tend to occur during the first three hours of sleep.

Image Credit: arka38 / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: arka38 / Shutterstock.com

Managing nightmares versus night terrors

In most cases, children grow out of both recurrent nightmares (nightmare disorder) and night terrors. Frequent nightmares can cause children to associate bedtime with anxiety and fear. Creating a predictable and calming bedtime routine and soothing children immediately upon awakening are strategies that may help.

When nightmare disorder occurs in adulthood, it often follows a traumatic experience. Recurrent nightmares are a diagnostic feature of post-traumatic stress disorder. In these cases, appropriate trauma-based talking therapies or medications such as Prazosin may be beneficial.

Night terrors may be treated by addressing an underlying disorder such as a comorbid mental health problem, or respiratory problems that lead to fractured sleep. As people may be mobile during night terrors, it is essential to ensure that their surrounding environment is safe to prevent injuries.

It is not helpful to attempt to wake someone during a night terror as they may be disoriented or aggressive. Instead, they should be offered quiet non-physical reassurance until the episode has ended.

Keeping a sleep diary can highlight patterns in their occurrence: if attacks occur at a similar time after falling asleep the person can be gently woken prior to an episode, then soothed back to sleep. Medication is rarely used but a small body of research has shown benzodiazepines and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may be beneficial in adults.

References

Agargun, M., Cilli, A., Sener, S., Bilici, M., Ozer, O., Selvi, Y. and Karacan, E., 2004. The Prevalence of Parasomnias in Preadolescent School-aged Children: a Turkish Sample. Sleep, 27(4), pp.701-705

Aurora, R., Zak, R., Auerbach, S., Casey, K., Chowdhuri, S., Karippot, A., Maganti, R., Ramar, K., Kristo, D., Bista, S., Lamm, C. and Morgenthaler, T., 2010. Best Practice Guide for the Treatment of Nightmare Disorder in Adults. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 06(04), pp.389-401.

Crisp, A., 1996. The sleepwalking/night terrors syndrome in adults. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 72(852), pp.599-604.

Simard, V., Nielsen, T., Tremblay, R., Boivin, M. and Montplaisir, J., 2008. Longitudinal Study of Bad Dreams in Preschool-Aged Children: Prevalence, Demographic Correlates, Risk and Protective Factors. Sleep, 31(1), pp.62-70.

Sleepeducation.org. 2020. Overview. [online] Available at: <http://sleepeducation.org/sleep-disorders-by-category/parasomnias/nightmares/overview/> [Accessed 1 October 2020].

Spoormaker, V., Schredl, M. and Bout, J., 2006. Nightmares: from anxiety symptom to sleep disorder. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 10(1), pp.19-31.

Szelenberger, W., Niemcewicz, S. and DĄbrowska, A., 2005. Sleepwalking and night terrors: Psychopathological and psychophysiological correlates. International Review of Psychiatry, 17(4), pp.263-270.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jan 11, 2021