The mesothelium consists of a single layer of avascular flat nucleated cells that lines serosal cavities and the majority of internal organs. The mesothelium plays an important role in maintaining normal serosal integrity and function. The exact mechanism of how mesothelioma, which is a highly aggressive tumor with a dismal prognosis, develops remains unclear.

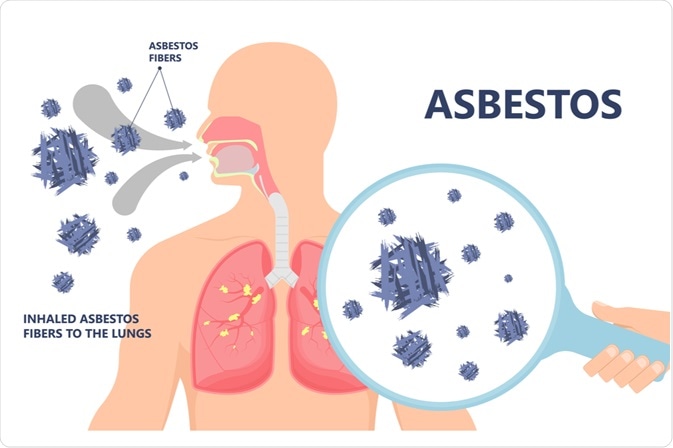

The pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for mesothelioma have been linked to asbestos fibers such as curly, serpentine fibers (white asbestos), or long chain-like fibers such as amosite (brown asbestos), crocidolite (blue asbestos), anthophyllite, tremolite, and actinolite. The pleura represents the target for the carcinogenic activity of asbestos due to the fact that asbestos can efficiently move from the lung to the pleural space, concentrating in the parietal pleura at the sites of lymphatic drainage.

Image Credit: rumruay / Shutterstock.com

Mechanisms of asbestos pathogenesis

During the long latency period of malignant mesothelioma, a myriad of pathogenic events may occur that can contribute to the development of the disease. After asbestos fibers are inhaled deeply into the lung and penetrate pleural space, prolonged cycles of tissue damage, repair, and local inflammation are initiated following the interaction of asbestos fibers with mesothelial cells. That, in turn, leads to carcinogenesis.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) induced by asbestos fibers with their exposed surface lead to DNA damage and stimulate a signal transduction cascade. Macrophages phagocytize asbestos fibers but are unable to digest them, thus resulting in the production of abundant ROS.

These events activate MAP-kinase signaling pathways through the epithelial growth factor (EGF) receptor. As a result, several of the induced transcription factors are highly expressed in mesothelioma.

Asbestos fibers can absorb different proteins and chemicals to the broad surface of asbestos, with the accumulation of hazardous molecules, including carcinogens, as a consequence. Once inside, asbestos fibers bind to important cellular proteins. The subsequent deficiency of these proteins can also be detrimental for normal mesothelial cells.

Asbestos Exposure | How It Leads to Mesothelioma (Complete Guide)

Macrophages and asbestos-exposed mesothelial cells produce a panoply of different growth factors and cytokines which induce inflammation and promote tumor development. These include tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), insulin-derived growth factor-1, interleukin-1β, transforming growth factor-β, granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factors, and platelet-derived growth factor.

TNFα has been shown to activate nuclear factor-κB, which seriously contributes to tumor formation and progression in mesothelioma. High-mobility group box 1 protein has also been shown to be released from mesothelial cells, which promotes an inflammatory response by establishing an autocrine circuit in mesothelial cells that influences their proliferation and survival.

Chromosomal aberrations

The long latency period between asbestos exposure and the development of mesothelioma, which can be up to 40 years, suggests that multiple genetic alterations are important in the conversion of normal cells to malignant mesothelial cells. Comprehensive karyotypic analyses have revealed that malignant mesotheliomas display multiple clonal chromosomal abnormalities, with over 10 of these abnormalities present in most cases of mesotheliomas.

Asbestos fibers are also engulfed by mesothelial cells, which can disrupt mitotic spindles and influence the cell cycle process. The tangling of asbestos fibers with mitotic spindles may result in chromosomal structural abnormalities and aneuploidy of mesothelial cells.

The loss of one copy of chromosome 22 represents the single most consistent chromosomal change in patients with mesothelioma. Specific deletions of chromosomal sites involve the short arm (p) of chromosomes 1, 3, and 9, as well as the long arm (q) of chromosome 6. Other nonrandom cytogenetic alterations can be found on other chromosomes as well.

Certain tumor suppressor genes located in the aforementioned chromosomal regions have also been implicated in the disease, including CDKN2A/ARF at chromosome band 9p21 and NF2 at 22q12. Mutations of the p53 gene, which is one of the most frequent genetic changes seen in the cancer cells, are occasionally observed in malignant mesothelioma as well.

It has also been postulated that simian virus 40 (SV40) can bind to and inactivate wild-type p53 in mesothelioma, thus interfering with DNA repair, as well as apoptotic and growth inhibitory functions. Although it is a DNA monkey virus, the probable route of transmission to humans was through the SV40 contaminated polio vaccines distributed between 1955 and 1978.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: May 23, 2021