Odontogenic keratocysts (OKCs) are benign, developmental cystic lesions of epithelial origin and involve the maxilla or mandible. These lesions are fairly aggressive locally and they have a high tendency to recur once they have been excised. Furthermore, they are known for their association occasionally with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS). Up to 70% of all OKCs occur in the mandible and the frequency of OKCs is particularly high between the second and third decades of life with a predilection for males.

Etiopathogenesis

OKCs are believed to arise from the vestiges of the dental lamina. Some studies have suggested that there is a potential link with the PTCH gene and the development of OKCs. Histologically, there is the recognition of three OKC variants, namely, parakeratinized OKCs, orthokeratinized OKCs and a third variant, which is a combination of the preceding two. Many investigators for quite some time now have debated the cystic nature of OKCs. These debates have led to some classifying OKCs in medical literature as benign tumors. Moreover, these discussions led to the World Health Organization replacing the name of OKCs with keratocystic odontogenic tumors (KCOTs).

The renaming of OKCs to KCOTs was done on the premise that it was a better reflection of the lesions’ tumor-like behavior. In support of this name replacement was the finding that OKCs had behavioral patterns that were aggressive in nature, and this was in addition to them having high histological mitotic activity and the evidence of their link with chromosomal and genetic anomalies. The latter takes into account the link and mutation seen with the PTCH gene. All things considered, these factors served as the basis for the name change, because they are all features of neoplasms.

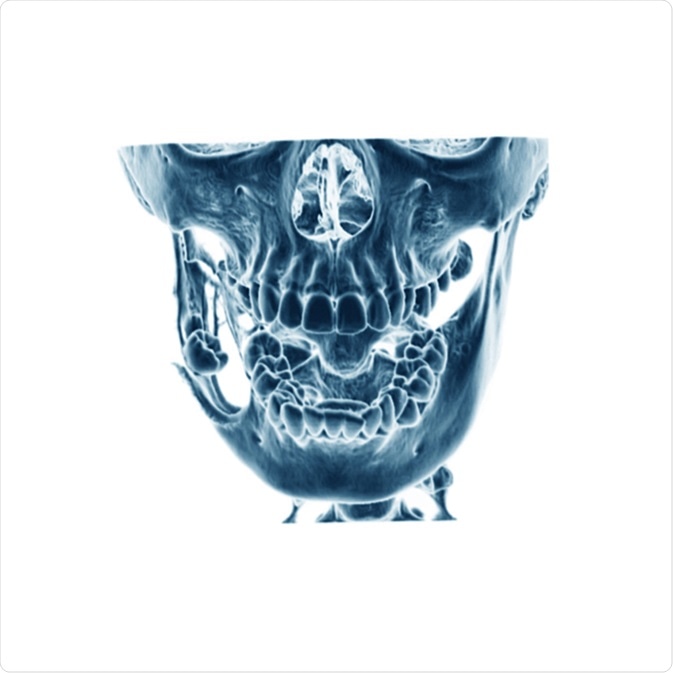

Ct scan (computed tomography) of dental mandible, case of keratocystic odontogenic tumor (right side). Image Credit: Suttha Burawonk / Shutterstock

Clinical Presentation

Persons with KCOTs may present with pain, swelling and discharge. However, some patients may also be asymptomatic as well. KCOTs can distinctively cause destruction of the local bone and when associated with NBCCS, which is also known as Gorlin-Goltz syndrome, they have a very high tendency to recur. This rate of recurrence may be as high as 82% when associated with NBCCS and it is as high as 60% when not associated with Gorlin-Goltz syndrome. Patients with this syndrome, in addition to the multiple KCOTs that they will have, also present with falx cerebri calcification, medulloblastoma, frontal bossing, bifid ribs and multiple epidermoid cysts.

Management

The management of KCOTs may be a bit controversial, but it is generally categorized into conservative and aggressive treatment. Exactly which approach is taken depends on factors such as the association of the lesions with NBCCS, in addition to the size, anatomic location and the pattern of recurrence. There is an array of surgical techniques for removal. These include enucleation, marsupialization, bone implantation, decompression and surgical resection, which can be radical or marginal.

A conservative approach may involve marsupialization and enucleation (i.e. surgical removal of masses without cutting into/ dissecting them) that may be done with curettage (i.e. the removal of tissue by scraping and/ or scooping) or without it. More aggressive treatment, such as ostectomy (i.e. bone removal) and surgical resection is generally used for cases associated with NBCCS or KCOTs that are very large or recur with high frequency. Despite treatment, KCOTs can recur, which occurs mostly in the first 5 – 7 years of treatment, but can be seen even up to a decade later.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Dec 29, 2022