Introduction

Medical mycology: A neglected area of microbiology?

Evolution of anti-fungal therapies

Recent advancements

References

Further reading

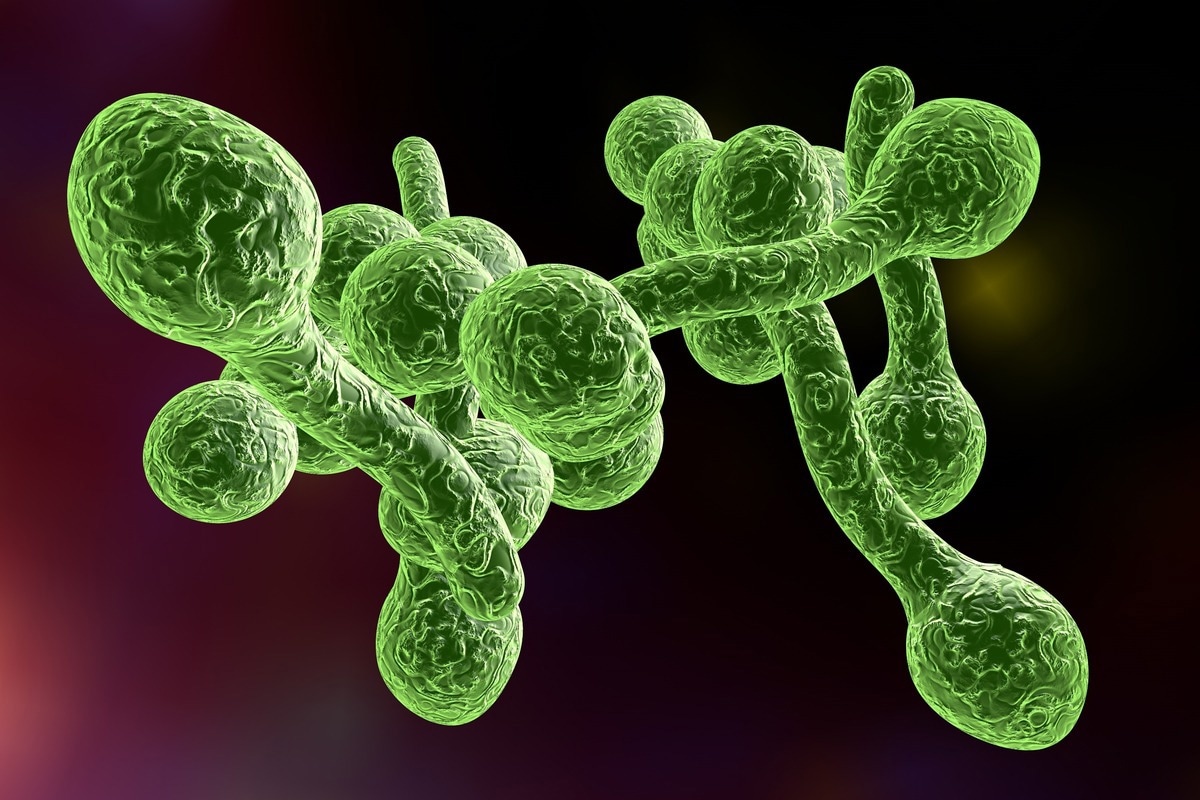

Fungal infections affect billions of people worldwide and, in severe cases can cause death. Yet medical mycology is a niche and neglected area of microbiology. Here we look at some common fungal infections, the therapeutic interventions used to treat them, how these have evolved and some of the more recent approaches that have served to aid our understanding of fungal pathology.

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock

Medical mycology: A neglected area of microbiology?

The isolation and identification of fungi is an often-neglected area of medical microbiology. The science known as medical mycology began in the early 19th century in Italy with the discovery of tinea favosa. The discipline concerns those infections in humans and animals that occur because of pathogenic fungi.

Fungi cause a range of diseases ranging from skin infections such as athlete’s foot, ringworm, dandruff, superficial cutaneous infections with dermophytes, to the more serious and invasive Candida and Aspergillus in severely immunocompromised hospital patients. Many important fungal pathogens seen in the immunocompromised also comprise part of the normal flora and this can lead to difficulties in detection.

It might seem surprising to learn that the global annual death toll due to fungal infections is greater than that for malaria, breast, or prostate cancer and more like those rates seen in tuberculosis (TB) and HIV (Gow, 2018). This toll runs to over a million people. In addition, around 10 million suffer from a severe fungal allergy; 100 million women annually fall foul to recurrent vulvovaginal infections and more than a billion people are afflicted by skin infections each year.

Candidas are ubiquitous in nature and can be found on many plants. They are also pathogens and saprophytes of both animals and humans that constitute the normal flora of the gut, the genitourinary tract, and the skin. The most common species in humans is Candida albicans but other species that can also cause trouble include G tropicalis, G glabrata, C krusei, G parapsilosis, and G pseudotropicalis. Of the several hundred Aspergillus spp. in nature there are just four linked to human pathogenicity: A fumigatus, A. flavus, A niger, and A. terreus.

Evolution of anti-fungal therapies

Gilchrist’s report of a medical case of blastomycosis saw the inception of medical mycology in the US in 1894. Over the course of the twentieth century further breakthroughs marked the discovery and characterization of dimorphic fungi, recognition of fungal pathogenicity and the part fungi play in systemic disease, the development of diagnostic tests in the laboratory, fungal classification, epidemiological and ecologic investigation.

The first kind of anti-fungal therapy, a saturated solution of potassium iodide (SSKI), turned out to be of limited clinical use and unsuccessful. The need for a broader spectrum anti-fungal, in addition to intravenous (IV) or oral anti-fungal agents was soon recognized, particularly as detection of fungal infections increased.

The first safe and effective anti-fungal treatments were discovered in Oxford in the late 1930s. In 1950 Hazen and Brown discovered nystatin, an important nod to the modern era of anti-fungal therapy. In the 1960s miconazole and clotrimazole were first introduced as topic agents. Then in the 1970s the broad-spectrum imidazole anti-fungals were developed and were active against dermatophytes, Candida, and other fungi.

Image Credit: OHishiapply/Shutterstock

Image Credit: OHishiapply/Shutterstock

The topical anti-fungal econazole was developed in 1974 and is still in use today. The early 1980s saw the introduction of an oral treatment for systemic fungal infections. The 1990s saw the most prolific period in anti-fungal development (Gubbins, 2009). The introduction of the broad-spectrum agent fluconazole in 1990 transformed anti-fungal development.

There are currently no vaccines or immunotherapies for mycoses and despite some important discoveries the range of anti-fungal drugs at our disposal to treat fungal infections remains limited. This neglected area of medical microbiology needs far more investment. New problems are arising all the time and the ongoing challenge of multidrug-resistant species poses a major threat to health.

In the UK, the research community is small with fewer than 60 principal investigators and just ten medical mycology specialist clinicians. There are three clinical mycology reference centres based in Leeds, Manchester, and Bristol and two specialist research centres: The MRC Centre for Medical Mycology, Aberdeen and the Manchester Fungal Infection Group and National Aspergillosis Centre at Manchester.

Read Next: Fungal Skin Infections

Read Next: Fungal Skin Infections

Recent advancements

Researchers have now defined the immunopathology of many fungal diseases. The pathology may be driven by fungal invasion and virulence in some cases while in others it results from an over-active inflammatory response. Recent research has advanced our knowledge of immunopathology with respect to specific fungal diseases.

Meanwhile, next-generation sequencing has altered our understanding of the genes that predispose some patients to specific fungal infections. This in turn has advanced our knowledge about the fundamental mechanisms of immune surveillance and recognition.

In addition, we can now better appreciate the interrelationship between these processes and that of the modulatory influence enacted by the microbiome and the mycobiome. These new insights bring future hope for a vaccine, adjunct immunotherapy, and a personalised approach to the treatment of fungal infections.

References

- Gillespie, S. et al. 1994. Medical Mycology. Medical Microbiology Illustrated. Pp. 113-124. Online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/medical-mycology.

- Gow, N. et al. 2016. Medical Mycology and Fungal Immunology: New Research Perspectives Addressing a Major World Health Challenge. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc., B.

- Doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0462.

- Gow, N. et al. 2018. Strategic Research Funding: A Success Story for Medical Mycology. Trends in Microbiology. Doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.05.014.

- Gubbins, P. et al. 2009. Antifungal Therapy. Clinical Mycology, 2nd Ed. pp. 161-195. Online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/immunology-and-microbiology/medical-mycology.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jun 21, 2022