Mastocytosis

Causes of systemic mastocytosis

Types and symptoms

KIT

Epidemiology of systemic mastocytosis

Diagnosis and treatment of systemic mastocytosis

References

Further reading

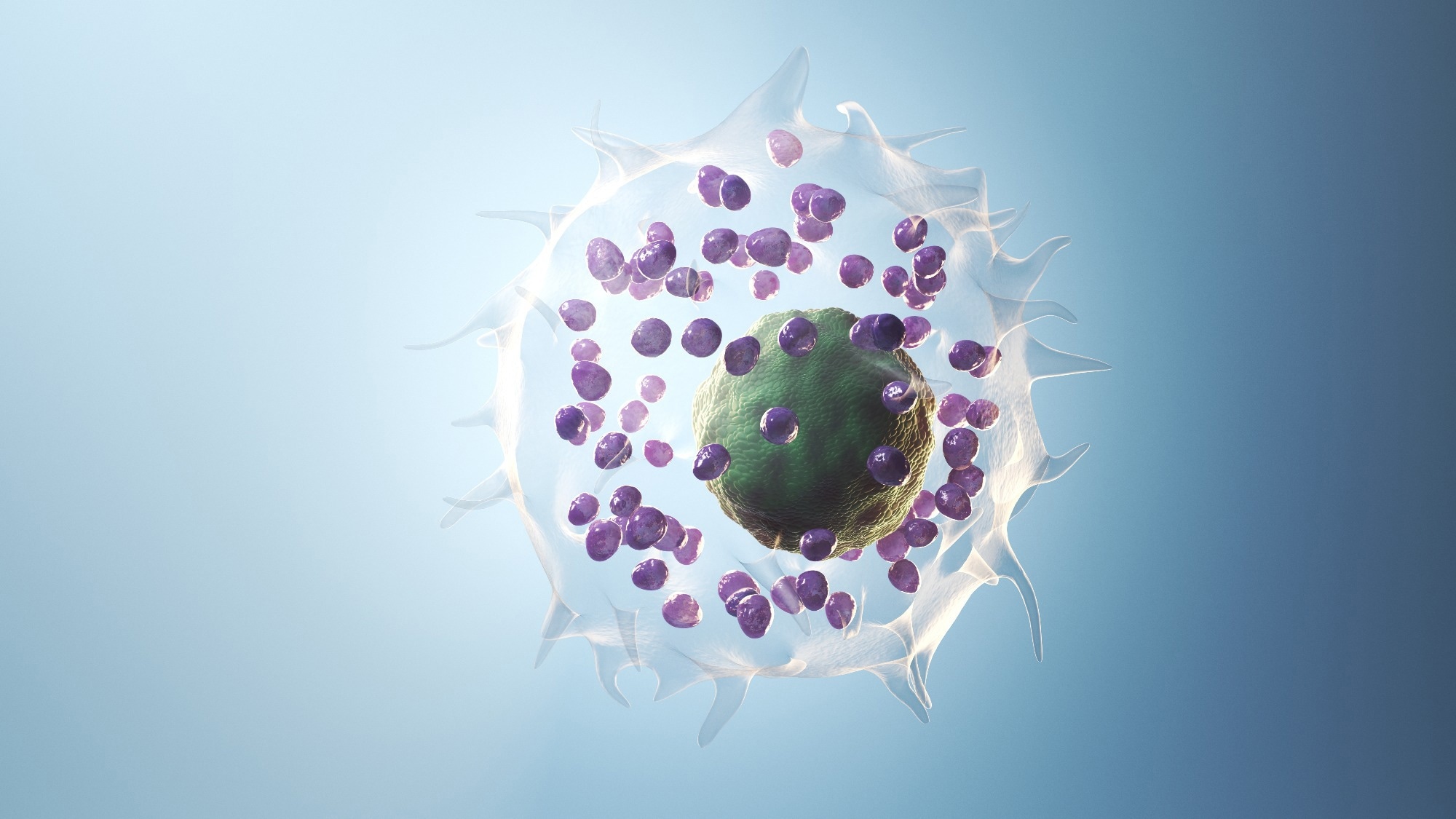

Systemic mastocytosis is a myeloid neoplasm divided into six subcategories by the recent classification by WHO. It involves the accumulation of abnormal mast cells (MCs) in the skin, liver, spleen, and bone marrow.

Systemic mastocytosis is a myeloid neoplasm divided into six subcategories by the recent classification by WHO. Image Credit: SciePro/Shutterstock.com

Systemic mastocytosis is a myeloid neoplasm divided into six subcategories by the recent classification by WHO. Image Credit: SciePro/Shutterstock.com

In the 1930s, the first case of SM was documented in France. More than 90% of SM patients have a KIT D816V gain-of-function mutation. Clinical and hybrid clinical-molecular risk models have recently been developed to better predict prognosis in SM patients.

Mastocytosis

Mastocytosis encompasses a heterogeneous group of clonal diseases, including cutaneous mastocytosis (CM), systemic mastocytosis (SM), and mast cell sarcoma (MCS).

It is distinguished by the proliferation and accumulation of neoplastic MCs in one or more organ systems, such as the skin, bone marrow, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, and gastrointestinal tract.

Cutaneous mastocytosis is the most frequent form of mast cell disease, accounting for 90% of cases. CM involves mast cell accumulation in the skin and affects children. MC sarcoma is a rare, aggressive form with metastatic potential and is prevalent among adults.

Causes of systemic mastocytosis

Systemic mastocytosis is usually linked to KIT somatic gain-of-function point mutations. TET2 is a potential tumor suppressor gene with mutation rates ranging from 20% to 29% in SM.

The majority of adult SM patients have gain-of-function somatic mutations in the KIT tyrosine kinase domain, specifically the D816V mutation. Other somatic KIT variants seen in adult SM that are less prevalent, include D820G, D815K, D816Y, D816F, D816H, insVI815-816, and V560G.

Types and symptoms

SM is prevalent among adults and has two forms – advanced and non-advanced. The advanced form is of 3 types – SM with an associated hematologic neoplasm (SM-AHN), aggressive SM (ASM), and MC leukemia (MCL), while the non-advanced form is divided into BM mastocytosis (BMM), indolent SM (ISM), and smoldering SM (SSM).

The most common subtype among adults is ISM. The indolent and smoldering forms of systemic mastocytosis are the mildest. Individuals with these types usually have the broad signs and symptoms of systemic mastocytosis, as described below.

Individuals suffering from the smoldering variant may have more organs impacted and more severe symptoms than those suffering from indolent mastocytosis.

Non-advanced forms are linked to a shorter life expectancy, which varies depending on the type and affected individual. They often involve the reduced function of an organ, such as the liver, spleen, or lymph nodes, in addition to the basic signs and symptoms of SM.

An inappropriate collection of fluid in the abdominal cavity can develop from organ malfunction. Aggressive forms also involve osteoporosis, osteopenia, and numerous bone fractures. MCL and SM-AHN both include blood cell diseases or blood cell cancer. MCL is the most severe and rare form.

Symptoms can be either due to the release of MC mediators or organ damage caused by MC invasion. Fatigue, nausea, skin redness and warmth, abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea are common signs and symptoms of systemic mastocytosis.

Other typical symptoms include nasal congestion, shortness of breath, hypotension, lightheadedness, and headache. Some people may suffer from attention or memory issues, as well as anxiety or depression.

Many individuals with systemic mastocytosis develop urticaria pigmentosa, characterized by raised areas of brownish skin that sting or itch when touched or when the temperature changes.

Nearly 50% of people with systemic mastocytosis will have severe allergic responses (anaphylaxis). Gastrointestinal symptoms, such as stomach acid backflow into the esophagus, are prevalent in 60-80% of SM patients and are one of the leading causes of morbidity.

KIT

KIT (CD117) is a Type III receptor tyrosine kinase expressed by MC, hematopoietic progenitor cells, germ cells, melanocytes, and Cajal interstitial cells in the gastrointestinal tract. The KIT gene codes for a protein that plays a key role in the formation and function of mast cells.

KIT expression is reduced when hematopoietic progenitors differentiate into mature cells of all lineages except MCs, which preserve high levels of cell surface KIT expression. The interaction of KIT and its ligand, stem cell factor (SCF), regulates MC proliferation, maturation, adhesion, chemotaxis, and survival.

Mutations produce a KIT protein that is always active. As a result, signaling pathways become hyperactive, resulting in increased mast cell production and accumulation.

Epidemiology of systemic mastocytosis

Systemic mastocytosis has an estimated prevalence of 1 in 10,000 to 20,000 worldwide.

Mastocytosis (NORD)

Diagnosis and treatment of systemic mastocytosis

The current SM diagnostic method begins with a BM examination because this location is usually involved in adult mastocytosis. The diagnosis of SM in the absence of skin involvement is significantly more difficult, especially in individuals with ISM variants with low MC burden and BMM, where serum tryptase is frequently normal or near normal.

KIT testing in peripheral blood can be used to assist in determining the clonality of mast cell aggregation. If there is a suspicion of a clonal origin of symptoms or refractory symptoms, KIT D816V should be investigated for probable clonality based on the patient's history.

Most advanced SM patients are treated by interventional therapy aimed at decreasing or eliminating neoplastic cells. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is the sole option for cure. In individuals with advanced SM, avapritinib is notably effective at reducing the proliferation of KIT D816V+ MCs.

Midostaurin is a broader-acting medication that inhibits several additional important targets in neoplastic MCs. Both of these inhibitors have approval for the treatment of patients with advanced SM by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency based on their activity profiles.

Alternative medications, such as cladribine, polychemotherapy, and HSCT, should be tried in patients with resistant SM. When the size and distribution of a skin lesion are limited, topical steroids can benefit. Cromolyn is useful in lowering GI symptoms, as well as in reducing bone pain and headaches.

For ISM individuals, therapy is typically limited to anaphylaxis prevention, symptom control, and treatment of osteoporosis. Advanced SM patients typically require MC cytoreductive therapy to improve disease-related organ failure.

Cladribine and interferon- are two further alternatives for MC cytoreduction, albeit head-to-head comparisons are sparse. If an aggressive disease such as acute myeloid leukemia is present, treatment focuses predominantly on the AHN component.

In such cases, particularly in those with relapsed/refractory advanced SM, allogeneic stem cell transplantation may be explored. Dasatinib also inhibits the tyrosine kinase activity of KIT D816V and has been demonstrated to be effective in aggressive versions. Several drugs are still in the early stages of clinical trials.

References

- Gotlib J, Kluin-Nelemans HC, George TI, et al. (2016). Efficacy and Safety of Midostaurin in Advanced Systemic Mastocytosis. The New England Journal of Medicine, 374(26), 2530–2541. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1513098

- Pardanani A. (2016). Systemic mastocytosis in adults: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk stratification and management. American Journal of Hematology, 91(11), 1146–1159. doi:10.1002/ajh.24553

- Scherber RM, & Borate U (2018). How we diagnose and treat systemic mastocytosis in adults. British Journal of Haematology, 180(1), 11–23. doi:10.1111/bjh.14967

- Pardanani A. (2019). Systemic mastocytosis in adults: 2019 update on diagnosis, risk stratification and management. American Journal of Hematology, 94(3), 363–377. doi:10.1002/ajh.25371

- Gilreath JA, Tchertanov L, & Deininger MW (2019). Novel approaches to treating advanced systemic mastocytosis. Clinical Pharmacology: Advances and Applications, 11, 77–92. doi:10.2147/CPAA.S206615

- Matsumoto NP, Yuan J, Wang J, et al. (2022). Mast cell sarcoma: clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of 10 new cases and review of literature. Modern Pathology: an Official Journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc, 35(7), 865–874. doi:10.1038/s41379-022-01014-w

- Valent P, Akin C, Sperr WR, et al. (2023). New Insights into the Pathogenesis of Mastocytosis: Emerging Concepts in Diagnosis and Therapy. Annual Review of Pathology, 18, 361–386. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-031521-042618

- Systemic mastocytosis. [Online] MedlinePlus. Available at: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/systemic-mastocytosis/

Further Reading

Last Updated: Sep 6, 2023