Endometrial hyperplasia (EH) is a condition in which the innermost lining of the uterus, or endometrium, undergoes thickening usually as a result of exposure to estrogen unbalanced by progesterone. It is usually diagnosed by microscopic examination of a sample of the endometrium. There are different types of EH which are important to differentiate, because one variant is strongly associated with a high risk of uterine carcinoma.

Credit: Jubal Harshaw/ Shutterstock.com

Diagnosis

Most women with endometrial hyperplasia present with abnormal uterine bleeding, which could include excessive menstrual bleeding, intermenstrual bleeding (or what looks like very short menstrual cycles, less than 21 days), prolonged bleeding, or bleeding after menopause (the periods have stopped altogether for a duration equal to or more than six normal cycles, and then recurred). In postmenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding, over 15 of every hundred will be found to have EH.

A woman of reproductive age who presents with abnormal vaginal bleeding may have to be evaluated for endometrial hyperplasia, among other conditions.

Transvaginal ultrasound scanning

A transvaginal ultrasound scan may be ordered to measure the endometrial thickness. A small probe emitting ultrasound waves is passed into the vagina and the reflected waves are then converted into a computerized image of the pelvic organs. The thickness of the endometrial lining is rarely over 4 mm in a woman past menopause. In premenopausal women the thickness varies with the phase of the menstrual cycle, but the maximum thickness will be within about 20 mm even in the secretory phase, when it is greatest.

Confirmation is by microscopic examination of a sample of uterine endometrial tissue. This may be obtained in several ways:

Blind endometrial biopsy

A slender plastic tube is inserted into the uterus and a small bit of the lining is withdrawn in a procedure which is easy, fast and does not need anesthesia. The drawbacks are that sufficient tissue may not be obtained, and the procedure may have to be repeated under hysteroscopy. Tissues lying below the surface are most likely to be missed. The presence of invasion of the abnormal cells into the muscle layer below is quite easily missed as well if most of the tumor is growing below the junction of the endometrium and myometrium, and this means a frank cancer can be quite commonly overlooked. In a third of cases tumors which penetrate muscle are comprised mostly of cells which penetrate deep but are not likely to show superficial spread, so that they will not be picked up on a surface biopsy.

Endometrial biopsy with hysteroscopy

Here a special camera is passed into the uterus to view the interior, and a guided endometrial sample is taken. This improves the chances of obtaining an adequate sample. However, it requires the use of advanced equipment and involves some discomfort. The use of hysteroscopy is rapidly advancing because it allows one to see the lesion and take directed biopsies, and is becoming easier to perform in the office rather than the operation room. This may become the gold standard in the near future.

Hysteroscopy with dilatation and curettage

Under hysteroscopic guidance, the cervix is dilated, and a narrow spoon-like instrument is passed in and used to scrape the uterine endometrium. The scrapings are sent for histopathological examination. This has the advantage of obtaining a greater amount of tissue for diagnosis. It requires special equipment and anesthesia as significant discomfort may occur.

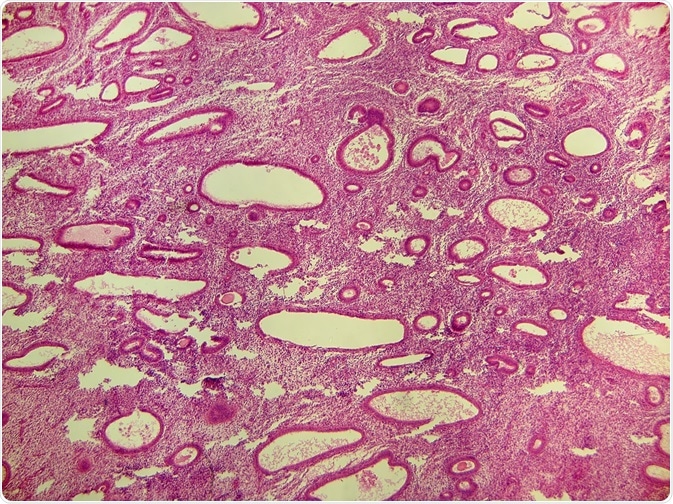

Microscopic appearance of EH

EH is classified into different groups based upon the type of cells and stroma (tissue separating the glandular cells) in the sample.

Older diagnoses used terms such as cystic-glandular hyperplasia and adenomatous hyperplasia. The WHO in 1994 used categories such as simple and complex hyperplasia, each of which included forms with and without atypia.

These terms are defined as follows:

Simple hyperplasia

- The endometrial glands appear dilated and cystic

- There is a lot of stroma with plenty of cells

- The glands are not crowded together

- Nuclei are uniform in shape

- There is no atypia

- The number of mitoses may be normal or increased to varying degrees

Complex hyperplasia

- Crowded glands of varying shapes

- Stroma is reduced

- Nuclei are uniform in shape

- The number of mitoses may be normal or increased to varying degrees

Atypia

- Nuclei are enlarged and round

- Chromatin shows irregular clumping

- Nuclear membrane may be thicker than usual

- Nucleoli are prominent

Endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN)

All the following criteria must be present for a diagnosis of EIN.

- Gland volume exceeds stromal volume so that the percentage of stroma by volume (VPS, volume percentage stroma) is less than 55%

- The lesion is more than 1 mm wide

- The endometrium in the lesion is not secretory or covering an endometrial polyp; it is not the basal endometrial layer; it is not showing signs of post-inflammatory repair; all these conditions may mimic EH appearances

- The cells in the lesion are very crowded, the glands are branching or show budding, and look different from those in the surrounding area

- There are no solid or cribriform areas, or maze-like branching glands which represent frank cancer rather than EIN

Pathologists found it difficult to make accurate diagnoses based on the microscopic examination, and the diagnosis often changed when the specimens were reviewed by other pathologists, because of the overlap between categories and the lack of clear differentiators. As a result, simpler classifications were evolved.

Several systems of classification have been put forward, but those more often used to report the diagnosis include the revised WHO 2014 classification and a German system by Mutter and The Endometrial Collaborative Group (2000). The revised WHO classification (2014) stressed the presence of atypia rather than simple or complex architecture. It thus includes:

- Hyperplasia without atypia

- Hyperplasia with atypia

These correspond roughly to the Mutter categories as follows:

- Endometrial hyperplasia (EH)

- Endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN)

A third system was put forward by a European expert study group (1999) which names the new histological groups endometrial hyperplasia (EH) and endometrioid neoplasia (EN).

Benign hyperplasia or hyperplasia without atypia are lesions which will resolve with conservative management (i.e., without surgery). There are no genetic changes characteristic of malignancy. On the other hand, atypical hyperplasia, EIN, or EN, is associated with existing invasive endometrial carcinoma or a high risk of such tumors within a few years, and the lesions show the characteristic mutations in tumor suppressor genes or DNA repair genes, as well as microsatellite instability. The recommended treatment for EH with atypia is total hysterectomy.

The advantage of these systems is that it is easy to achieve a reproducible diagnosis based on the microscopic appearance of the endometrial sample. The categories are differentiated by simple criteria regarding the cellular shape, size, branching, nuclear size, presence of nucleoli, strongly eosinophilic cytoplasm, and other morphological aspects. Further confirmation is by assessing the ratio of stroma to total volume of the tissue. This will help make diagnosis easier, more accurate, with minimal interobserver variability, and better clinical interpretation.

In order to standardize classification and treatment of these lesions, it is essential that a single system be used worldwide to ensure that comparable diagnosis and treatment standards are available for research.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 26, 2019