The perception of taste varies according to the genetic makeup of different individuals and this genetic influence on taste was discovered in the 1930s.

A chemist named Arthur Fox, a chemist, accidentally blew a chemical compound called phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) into the air and he noticed that a few of his colleagues felt the compound tasted bitter but Fox and other colleagues could not taste anything.

Geneticists later discovered that an inherited component determines how people taste PTC. After years of research, in 2003, the gene coding for the taste receptor for PTC on the tongue was identified as TAS2R38.

According to researchers, not only taste but the general eating behavior of humans including meal size and calorie intake are controlled by our genes. Studies on families and twins have found links between genetic makeup and preference to proteins, fat and carbohydrates.

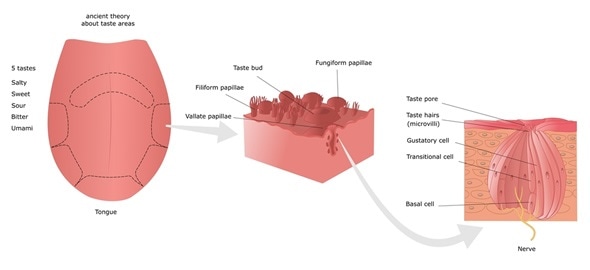

Sensory nerves: the taste; tongue and its papillae. Image Copyright: ellepigrafica / Shutterstock

The study of the influence of genes on our diet has developed into a new field called nutrigenetics. Today, this is a rapidly growing field, thanks to general curiosity, advances in technology and innovative genetics projects, such as the Human Genome Project that maps the entire human genome.

Research on Taste Receptors

In 2006, researchers from the Monell Chemical Center based in Philadelphia found that glucosinolates, a group of bitter bitter tasting compounds present in certain vegetables and fruits, including broccoli, bok choy, kale and turnips, are detected by the bitter taste gene receptor hTAS2R38. About 35 adults who express three genotypes ( hTAS2R38: PAV/PAV, PAV/AVI, and AVI/AVI) were tested as part of this study. People having PAV/PAV were found to be highly sensitive to bitter taste in several foods including tea, coffee, vegetables and grape juice – they were called supertasters. People with PAV/AVI were found to be regular tasters who can taste bitter foods though much less intensely than supertasters. People with AVI/AVI were insensitive to bitter taste and were called non-tasters.

Beverly J. Tepper, scientist from Rutgers University, in an attempt to analyze how taste perception affected eating behavior, identified 65 preschool children who were grouped into tasters and non-tasters. When these children were given five kinds of bitter and non-bitter vegetables, non-tasters ate more bitter vegetables than tasters. Thus Tepper concluded that being able to perceive bitter taste does influence children’s food choices.

According to researchers, supertasters and regular tasters perceive not only bitterness, but also other spicy, sweet and salty tastes better than non-tasters. The receptors for universally preferred tastes such as sweetness are coded by the genes TAS1R3 and TAS1R4 and are also influenced by other factors such as race, age, mood, appetite and sex. A Monell Chemical Center study shows that supertaster and taster children opted for sugary drinks and cereal and did not prefer milk or water, unlike non-tasters. However, adults showed no such preferences, possibly influenced by culture or long associations with different tastes and also awareness about healthy options.

Summary

Globally, the number of tasters and non-tasters varies widely across different populations for unknown reasons. In some populations such as Japanese, Chinese and West Africans, non-tasters account for as little as 3% of the population. Roughly 70% of people in North America are bitter tasters and 30% are non-tasters. Surprisingly, about 40% of Indians were found to be taste blind during a study.

All the intense publicity about the genes influencing our ability to taste different foods is yet to create any major change in the field of dietetics. Dieticians are hoping that a simple tool that helps evaluate genetic profiles of patients will help them prescribe customized diets to patients in the near future.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jun 25, 2019