Lung cancer represents the leading cause of death from malignancies in men and women around the world. The seriousness of the problem is reflected in the number of people who succumb to lung cancer each year, which has risen sharply in the last 25 years and exceeded the number of deaths from breast, colorectal and prostate cancer combined.

Although various factors are implicated in increasing the risk of lung cancer development, cigarette smoking remains the most salient one. Since symptoms are usually not apparent until the malignant process is already in the advanced stage, it is of no wonder that the basic idea of screening (i.e.searching for lung cancer in asymptomatic individuals) is so appealing.

In general, the primary goal of screening is to catch the disease at the earliest and most curable stage. However, many different criteria have to be met by a certain screening program if it is to be broadly accepted and recommended by the medical community. The most important one is to reduce the number of deaths from the disease in question.

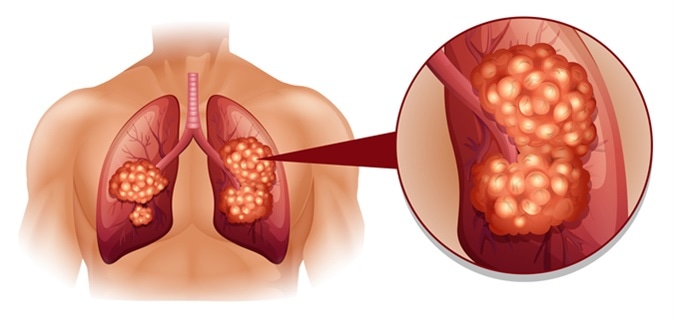

Lung cancer illustration. Image Credit: BlueRingMedia / Shutterstock

The Value of Screening for Lung Cancer

Lung cancer screening is currently recommended for elderly individuals who have a long-time history of smoking and who do not exhibit any symptoms or signs of lung cancer. It has to be emphasized that successful screening endeavors necessitate a multidisciplinary organization that is centered on diagnosing and treating participants identified with having lung cancer with great precision, but also minimizing potential harms to the majority of screenings without the malignancy.

As there can be huge differences according to the actual screening environment and prevailing conditions, the screening program should always be adapted to local conditions while still preserving a high-quality performance. In addition, local or country-specific research studies are encouraged in order to determine whether screening for lung cancer actually makes sense.

In such studies, smokers that are at the highest risk are first divided into different groups. Certain groups are subjected to screening tests, while no screening is done to the other groups. All of them are followed for many years, with the concomitant gathering of data on the number of diagnoses, the number of treated patients and treatment modalities used, but also adequate survival and mortality data.

Low-Dose CT Scan

Screening for lung cancer by means of low-dose computed tomography (CT) scan has been demonstrated to decrease the death risk for individuals over the age of 55 years with a long history of smoking. This type of imaging uses X-rays to produce comprehensive cross-sectional images of the lung, with substantially better results in finding tumorous lesions and showing them clearly when compared to regular X-rays.

Moreover, the National Lung Screening Trial conducted in the United States showed that such low-dose CT screening has the propensity to reduce lung cancer mortality by 20% in high-risk patients in comparison to chest radiography. The benefit is so stark that the potential radiation risk pales in comparison, as approximately one cancer death can be attributed to CT radiation from 2,500 people screened.

Hence, yearly screens using low-dose CT scan is now a part of standard recommendation bundle of a plethora of organizations for either current or former smokers with a long smoking history. Naturally, guidelines may vary among organizations in accordance with the specific criteria used, most notably age and smoking history.

False-positive tests increase the need for follow-up tests, such as more radiology imaging, but sometimes also biopsies, which invariably carries risks such as radiation exposure and biopsy complications. This means that the downsides inherent to screening always have to be taken into account.

What to expect during a low dose CT scan

Other Screening Modalities

A standard practice by many health care providers around the world is performing a chest X-ray once a year for all the patients who smoke; nonetheless, studies did not show any benefit, so current guidelines are against this practice. This is also supported by large studies that aimed to compare chest X-ray with low-dose CT scan in lung cancer screening endeavors, which showed that only CT reduced the risk of death.

Some researchers have also looked at whether there is any benefit of sputum analysis where cancer cells are sought in order to detect (and indirectly confirm) lung cancer. Still, thus far no benefits to this approach have been demonstrated, although further studies employing novel technologies for sputum examination are underway.

A myriad of other tools are studied to find an even more efficient and quicker way to identify individuals with lung cancer. For example, positron emission tomography (usually abbreviated to PET scanning) uses small amounts of radioactivity for detailed visualization of an organ’s function, usually in combination with CT scanning. Nevertheless, there is a much higher dose of radiation when compared to CT alone, with no additional benefit for screening purposes.

Other studies (such as cancer markers in the blood, breath analysis and bronchoscopy) are still not routinely used, albeit they may be useful in the future. In conclusion, incorporating validated risk biomarkers for preclinical lung cancer detection may substantially enhance the effectiveness of used screening programs, with subsequent major public health ramifications.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Apr 8, 2021