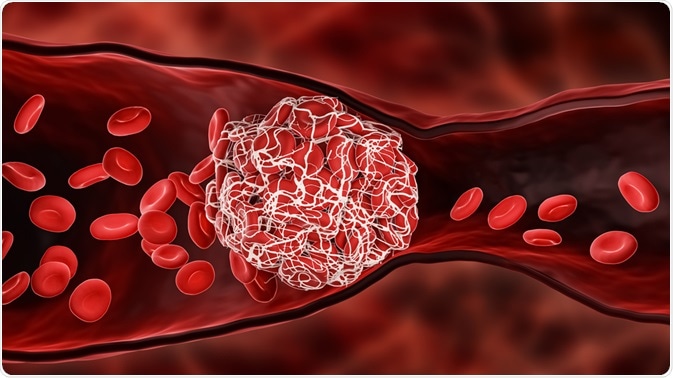

Warfarin is an oral anticoagulant drug and remains the most widely used in its category. The primary use of warfarin is to prevent and treat venous thrombosis, as well as to prevent and stop the extension of clots. This is also the rationale for its use in atrial fibrillation.

Image Credit: MattLPhotography / Shutterstock.com

Common indications

Warfarin is often used for the prevention of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), such as that which may occur following major gynecologic or hip surgery, as these procedures often cause prolonged immobilization. DVTs are also sometimes associated with chemotherapy for some malignancies.

An International Normalized Ratio (INR) of 2 to 3 with warfarin is usually sufficient. The duration of warfarin prophylaxis in such cases is usually three months.

Warfarin is also used in the treatment of venous thrombosis, whether spontaneous, recurrent or associated with risk factors, such as the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome or other thrombophilias. Proximal venous thrombosis, as well as recurrent thrombosis, warrant prolonged therapy for 6-12 months, while thrombosis secondary to thrombophilic conditions requires lifelong therapy.

Warfarin may also be used in the prevention of both pulmonary embolism and systemic embolism, the latter of which is present in atrial fibrillation. The later condition predisposes the individual to cardiac chamber thrombosis and embolic stroke.

Finally, warfarin may also be used to aid in the prevention of systemic embolism in mechanical heart valves, as these are prone to develop thrombosis. While this treatment is beneficial for the patient, the use of warfarin increases the patient's risk of increased bleeding complications, when compared to antiplatelet drugs. Lifelong warfarin treatment is recommended, compared to three months of therapy with low-risk bioprosthetic valves.

How does warfarin work?

Other indications

Aside from the primary indications for warfarin, it is often used for several other health conditions. For example, warfarin is used for the primary prevention of acute myocardial infarction in patients with peripheral arterial disease or other high-risk factors. Despite its widespread use for this purpose, clinical trials have not provided unequivocal evidence of any significant benefit from the use of low-dose warfarin prophylaxis.

More doubtful indications for warfarin include the prevention of recurrent transient ischemic attacks, and repeated myocardial infarction, stroke, or death in patients with an acute myocardial infarction. The choice of aspirin alone seems to be preferable to aspirin in combination with low-, moderate-, or high-intensity warfarin, when the treatment efficacy and incidence of bleeding complications are compared with the reduction in relative risk of these conditions.

Warfarin may also be used for the prevention of systemic embolism in mitral stenosis with sinus rhythm, as well as atrial fibrillation associated with valvular heart disease

Treatment with warfarin for patients diagnosed with systemic embolism as a result of a congenital heart defect such as patent foramen ovale, or other unknown cause, is also common practice. In addition to systemic embolism due to this congenital malformation, warfarin is also used in the prevention of systemic embolism in dilated cardiomyopathy.

In most situations, the dose of warfarin is adjusted in the individual patients to maintain an INR of 2 to 3. Warfarin dosage and maintenance is a problem because of its narrow threshold of safety and long half-life in circulation. This leads to a dose-response relationship which makes toxicity as well as ineffective treatment a frequent possibility. The aim of therapy is to make sure the patient receives the dose of warfarin that is the lowest possible to keep clots from forming or extending.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: May 23, 2021