Sheehan’s syndrome is a condition in which the pituitary gland suffers necrosis after severe postpartum hemorrhage, which occurs in almost a third of such cases. It is named after Harold Leeming Sheehan who first characterized it. The condition is most commonly observed in the poorer regions of the world where women are most likely to suffer from severe hemorrhage following childbirth, and it often occurs at home.

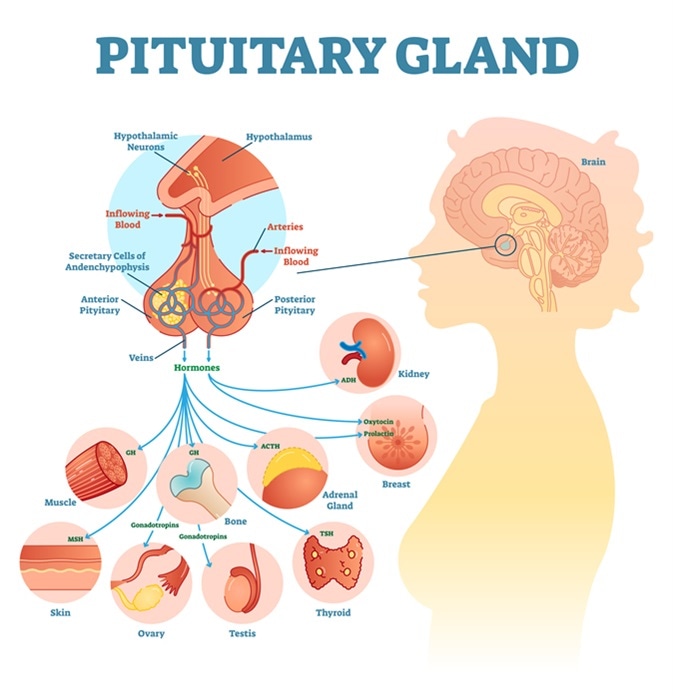

Pituitary gland anatomical illustration with brain and hormone types. Image Credit: Vector Mine / Shutterstock

The necrosis is ischemic in nature, but spasm, clot formation, or compression of the vessels supplying the pituitary gland may also be involved. In some cases it is thought to occur as a complication of cramped conditions within the sella turcica (the bony socket in which the gland rests), autoimmune or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)-like complications. Anti-pituitary antibodies (APAs) have been found in a small number of patients.

The anterior pituitary is affected in a majority of cases, but the posterior part may also be damaged (although rarely). The symptoms of hypopituitarism appear months to years after the episode of hemorrhage, with an average lag period of about 13 years. Approximately 75% loss of pituitary tissue has occurred by the time the manifestations are observed.

Clinical Presentation

Sheehan’s syndrome is characterized by lactation failure in the postpartum period, but this is observed in some cases only. Growth hormone deficiency is a common feature because of the propensity of the cells that secrete this hormone to suffer ischemia, being located in the lower and outer parts of the gland. Other features which may occur much later include:

- amenorrhea (failure to have normal periods)

- loss of axillary and pubic hair

- appearance of wrinkles around the eyes and lips

- weakness and loss of weight

- early aging

- dryness of the skin

- loss of pigmentation

Less common, but more severe symptoms include:

- Circulatory collapse

- Severe lowering of blood sodium levels, or hyponatremia

- Diabetes insipidus or passage of excessive quantities of dilute urine due to the lack of anti-diuretic hormone from the posterior pituitary

- Hypoglycemia

- Congestive heart failure

- Severe mental changes

In all progressive pituitary lesions, the manifestations are the same and occur in the same sequence - namely, loss of somatotrophs (growth hormone-secreting cells), followed by gonadotrophs and thyrotrophs last (producing gonadotropins such as FSH/LH and thyroid hormone, respectively).

The differential diagnosis of Sheehan’s syndrome is a non-functioning adenoma. However, patients with Sheehan’s are likely to be still young when the clinical features become obvious; furthermore, they have reduced levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) levels, and growth hormone levels are low, needing to be replaced for optimum restoration of the normal health, lipid profile and quality of life.

Diagnosis and Management

Sheehan’s syndrome is diagnosed by the finding of an empty or partially empty sella, in about 70% and 30% of patients, respectively. Management is focused on identifying missing or deficient hormones and replacing them, to ensure that patients with hypopituitarism do not succumb to circulatory collapse. Growth hormone deficiency should also be corrected.

Cortisol deficiency is life-threatening and should always be treated with glucocorticoids before giving thyroid hormone replacement. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is required to treat gonadotropin (FSH/LH) deficiency. Fertility treatment is required for those who want to conceive. In addition, diabetes insipidus is treated by replacing ADH with the synthetic analog 1-desamino-8-d-arginine vasopressin (desmopressin, DDAVP).

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 27, 2019