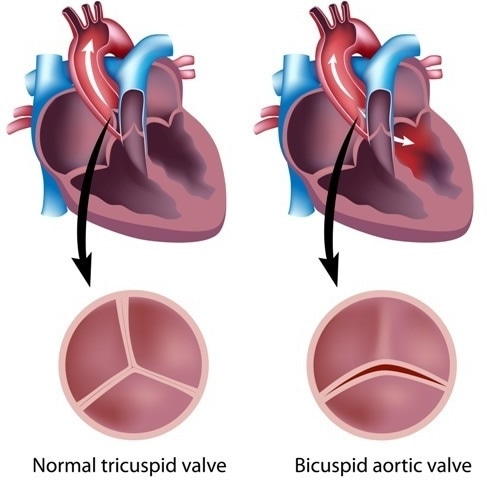

A bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) is the most common form of congenital heart disease and is present in about 2% of the population, affecting twice as many males as females. It is an abnormal form of the aortic valve between the heart and the aorta, the great vessel which supplies blood to the whole body except the lungs. In the normal form this is composed of three leaflets which meet securely when they close to keep blood from flowing back into the heart when the lower left heart chamber or ventricle relaxes.

In most cases of BAV the patient is asymptomatic at first, as the degree of leakage of blood back into the heart is too small to produce symptoms. However, necropsy series show that only about 15% to 20% of BAV show normal function.

Heart valve defects. Image Credit: Alila Medical Media / Shutterstock

Causes

BAV is caused by a connective tissue disorder in most cases. It may be associated with other vascular anomalies and with labile hypertension. It often shows a familial tendency.

Symptoms

BAV causes symptoms only when complications occur. The patient may then complain of easy fatigability, chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations due to heartbeat irregularities, syncopal attacks and anemia.

Complications

The majority of BAV patients eventually develop serious complications as they grow older due to calcification and fibrosis around the valve defect, which makes it rigid. BAV may be associated with coarctation of the aorta, may cause aortic regurgitation (leakage of blood back into the left ventricle) and aortic stenosis (narrowing of the valve so that the left ventricle strains to get enough blood through the opening), which is seen to occur in up to 70%, as well as aortic aneurysm due to weakness of the aortic wall. It is said that BAV is present in 50% of cases of severe aortic stenosis. In this condition, the cusps are more often asymmetrical and are oriented in the anteroposterior plane. Other risk factors for aortic stenosis include dyslipidemia and smoking.

Infective endocarditis (infection of the heart’s inner lining) which may occur in younger patients, at 10% to 40%, and heart failure are other complications.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of BAV may be incidental when the child undergoes an echocardiogram for other anomalies, or it may be due to the presence of symptoms. Warning signs include loss of appetite, pallor or cyanosis, and easy fatigability. Most patients will then show signs such as cardiomegaly, heart murmur, or a weak pulse in the wrists and ankles.

Tests to confirm the condition include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), cross-sectional and Doppler echocardiogram, a chest X-ray and ECG, and cardiac catheterization as well as magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) in some cases. The use of echocardiography improves the predictive accuracy to about 93%.

Treatment depends upon the severity of the defect and associated complications. Surgical repair or replacement is often needed. Cardiac catheterization and balloon valvuloplasty may also be attempted. Medical treatment may include inotropics to strengthen heart contraction, beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors to relax the blood vessels, and diuretics to reduce swelling. Genetic counseling may help in decisions regarding pregnancy if the condition seems to run in the family.

Prognosis

The prognosis depends upon the presence of other complications and how they are treated. Calcified and fibrosed valves are more prone to be stiff or to regurgitate blood back into the heart.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 26, 2019