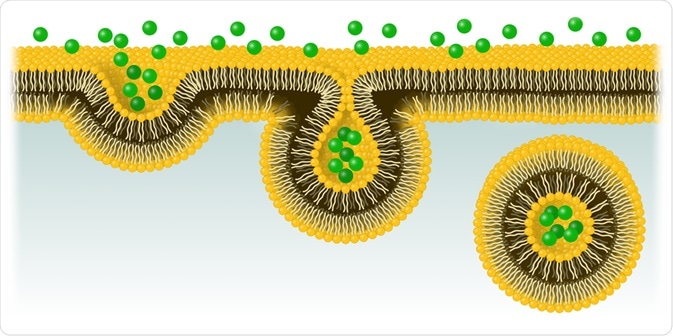

Endocytosis is a cellular process whereby molecules that cannot pass through a cell membrane passively are actively transported from the extracellular environment into the intracellular environment.

Image Credit: J. Marini / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: J. Marini / Shutterstock.com

The process involves the invagination of the cellular membrane, which develops into a vesicle containing the ingested material that buds off inside the cell. This active form of transport includes stages of pinocytosis and phagocytosis.

Endocytosis has an opposing process, known as exocytosis, where molecules are actively exported out of the cell. Both of these processes work in harmony to ensure that the same amount of molecules leave the cell as enter it, achieving homeostasis by maintaining an equal flow in and out. This helps the body maintain a balance of incoming nutrients and outgoing waste so that the regular function of the cell can continue.

Below, we discuss the process involved in endocytosis in further depth.

The components of endocytosis

The main components that feature in mammalian endocytosis are early endosomes, late endosomes, and lysosomes. Early endosomes act as the first compartment of endocytosis. They are found at the cell’s membrane and receive almost all types of vesicles approaching the cell’s surface.

Their main role is as sorting organelles, their slightly acidic pH facilities the dissociation of endocytosed ligands from their receptors, many of which are transported via tubules back to the cell’s surface and out into the extracellular environment. Additionally, early endosomes are the location of sorting into the transcytotic pathway, where molecules are transported into late endosomes or lysosomes via transvesicular compartments.

Late endosomes are the next component implicated in the endocytic pathway. These vessels receive endocytosed material from the early endosomes, as well as from phagosomes and trans-Golgi networks.

Late endosomes contain proteins that are the building blocks of structures such as mitochondria and nucleosomes, as well as acid hydrolases and lysosomal membrane glycoproteins. They are also part of the trafficking pathway for transmembrane glycoproteins such as mannose-6-phosphate receptors. Late endosomes are considered to be the site of the final sorting events of endocytosis before the material is passed onto the lysosomes.

The final component of the endocytic pathway is the lysosomes. The main role of these structures is to lyse carbohydrates, fats, proteins, waste products, and other molecules into simpler compounds.

Lysosomes utilize around 40 different types of enzymes, produced in the endoplasmic reticulum and further processed in the Golgi apparatus, to successfully carry out their function of breaking down these products. Once the lysosomes have broken down this material, the resultant compounds are often returned to the cytoplasm where they are enlisted into cell-building activities.

Clathrin-dependent endocytosis

In most eukaryotic cells, the main route to endocytosis is mediated by the protein clathrin. While the clathrin-mediated pathway is probably the best-understood route of endocytosis and has been studied for many years, our understanding of the mechanisms of the pathway continues to develop as new technologies emerge that allow us to visualize the workings of the pathway on an unprecedented scale.

These newer studies have given us key insights into the structure and dynamics of the proteins implicated in clathrin-dependent endocytosis.

The pathway plays a key role in transporting extracellular molecules as well in the mediation of bacteria, toxins, and viruses attempting to enter the cell. Currently, it is not clear how long clathrin-coated vesicles (CCVs) or clathrin-coated pits (CPPs) exist, with studies suggesting time frames of seconds to minutes.

Recent evidence has been produced from research projects utilizing quantum computing to analyze the dynamics of CCV and CCP formation. These studies have highlighted three distinct populations of CCPs that can be defined by their unique kinetic properties.

Two of which are described as short-lived, with a lifespan of just seconds, and one defined as long-lived, with a lifespan of over a minute. Studies have shown that, in the presence of cargo, a cell will respond by producing a greater number of long-lived CCPs/CCVs.

Other newer technologies such as cryo-electron tomography have been used in recent studies to successfully develop our knowledge of the clathrin-mediated pathway. Cryo-electron tomography has revealed the range of patterns utilized to organize the lattice of the clathrin vesicles.

Further to this, high-resolution imaging has uncovered the nonsymmetrical localization of AP-2 adaptor proteins within individual CCVs which may be the result of an initial stage of restricted localization of adaptors.

Finally, further studies have revealed the specialized functions of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in various tissues, such as the nervous system. Specifically, the dynamin-1 protein has been shown to be unessential for the roles of synaptic vesicle synthesis and endocytic recycling, which previous studies have suggested. More recent knockout (KO) studies in mice have revealed that this protein’s role in synaptic vesicle endocytosis is activity-dependent.

As technology continues to evolve, we can expect studies to continue to visualize the pathways of endocytosis in even finer-grain detail. This will help with our understanding of homeostasis, and also of bacterial and viral infections.

Sources

Alanko, J., Hamidi, H. and Ivaska, J., 2016. Signaling from Endosomes. Encyclopedia of Cell Biology, pp.211-224. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123944474200163

Cheng, Y., Boll, W., Kirchhausen, T., Harrison, S. and Walz, T., 2007. Cryo-electron Tomography of Clathrin-coated Vesicles: Structural Implications for Coat Assembly. Journal of Molecular Biology, 365(3), pp.892-899. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1839968/

Miaczynska, M. and Stenmark, H., 2008. Mechanisms and functions of endocytosis. Journal of Cell Biology, 180(1), pp.7-11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2213624/

Further Reading

Last Updated: Dec 22, 2020