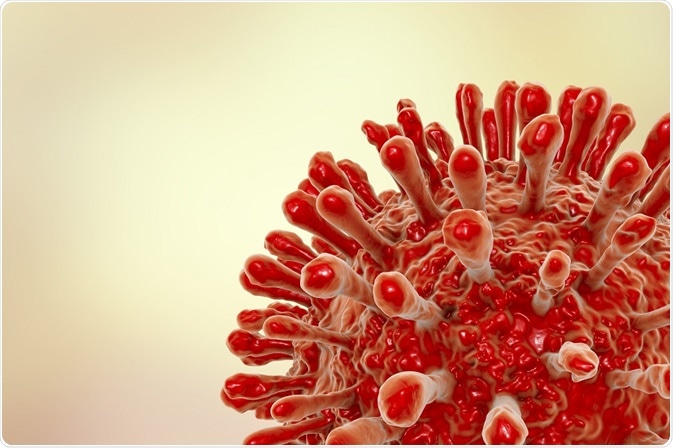

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the virus that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a disease characterized by progressive deterioration of the immune system ultimately leading to death, usually from cancer or infection.

Credit: Katryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

Credit: Katryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

HIV is a lentivirus, a type of retrovirus, or RNA-based virus. When the virus enters cells, its single-stranded RNA genome is reverse-transcribed into double stranded DNA by reverse transcriptase.

Viral DNA is then imported into the nucleus and integrated into the cellular genome, where it reproduces. The success of HIV depends on its ability to evade the host’s immune system. Mounting evidence suggests that multiple mechanisms are involved in that process.

Evading cellular innate immunity

HIV has a unique quality in that it does not alert the host’s innate immune defenses and does not induce type I interferon (IFN), a typical marker of antiviral response that inhibits viral replication and primes the adaptive immune system.

This lack of IFN response seems to be critically important to the virus’s ability to evade the immune system. Researchers hypothesized that uncoating of the virus and entry into the nucleus are critical steps in viral replication for evasion of innate immune sensors.

Mechanistic studies of uncoating and nuclear transport shed some light on this cloaking effect. One study identified a protein, cleavage and polyadenylation factor 6 (CPSF6), that, when truncated at its C-terminal end, restricts HIV-1 infection. In cells expressing CPSF6, nuclear entry was impaired.

A single amino acid substitution within the viral capsid (CA) protein restored the ability of the virus to enter the nucleus. This mechanistically linked CA to the process of nuclear transport.

Viruses with a mutation in CPSF6 trigger innate immune sensors leading to stimulation of IFN. Depletion of CPSF6 with short hairpin RNA expression also resulted in triggering of innate sensors and IFN production.

Replication of the virus can be rescued by blocking the IFN receptor. A similar effect resulted in a virus strain deficient in cyclophilins (Nup358 and CypA), suggesting that HIV-1 evolved to use CPSF6 and cyclophilins to cloak its replication, allowing it to evade innate immune sensors and inducing an innate immune response.

Other studies point to a role for SAMHD1, a restriction factor expressed in myeloid cells which seems to prevent HIV-1 infection in myeloid cells. Studies of the dendritic cell innate response to HIV-1 suggest that SAMHD1 may limit sensing of the viral nucleic acids by the host innate immune system.

Dendritic cells resist infection by HIV, while still having the ability to take up intact viral particles and hand them off to T cells. Multiple studies have shown that viral components that accumulate prior to integration of the viral genome, such as capsid protein and viral nucleic acids, did not activate dendritic cells. This is thought to be related to SAMHD1.

HIV life cycle: How HIV infects a cell and replicates itself using reverse transcriptase

Evading the adaptive immune system

HIV must also avoid detection and clearance by the adaptive immune system in order to replicate and spread to new hosts. The adaptive immune response relies on the ability of major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) to capture peptides and present them to T cells and natural killer (NK) cells.

A 2017 study published in Nature Structural and Molecular Biology showed how mutations in HIV can change how the MHC displays those fragments, resulting in the virus being hidden from the immune system.

Hope for the development of a future cure

Understanding the various mechanisms by which HIV evades the immune system could lead to improved treatments in the future.

Disabling the virus’s cloaking mechanisms would make it vulnerable to clearance by either the cellular innate immune system, the host adaptive immune system, or both. These mechanisms could be treated by therapeutic drugs targeting molecular elements of the cloaking system, or incorporated into a vaccine.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 26, 2019