A recently characterised form of cell death, called necroptosis, occurs when apoptosis cannot be carried out. The activation and subsequent stages of this pathway have been characterized during the past decade, showing that it is a form of programmed cell death, sharing very similar characteristics to both apoptosis and necrosis.

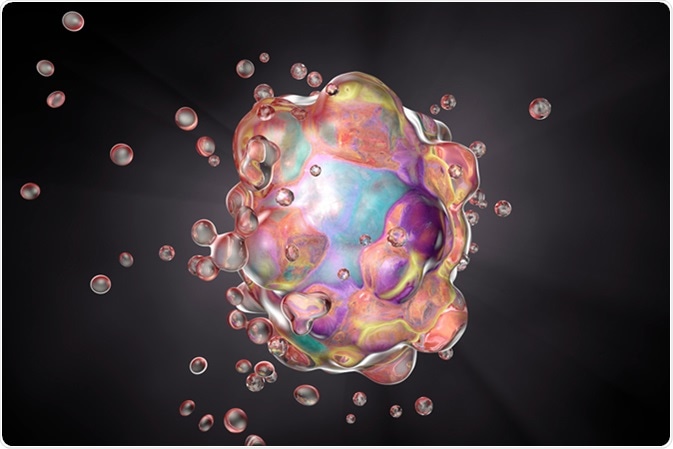

Apoptosis has been characterised as a form of programmed cellular death, resulting in shrinkage of the cell, chromatin condensation and degradation of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). This process is involved in a myriad of biological processes, including aging and disease.

Cell apoptosis, a process of programmed cell destruction that occurs in multicellular organisms, 3D illustration showing changes in cellular morphology, blebbing, cell shrinkage. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

Many different initiators, such as the BCL-2 family, and highly controlled activation pathways have been characterised, which are vital to prevent mass cell death and premature aging.

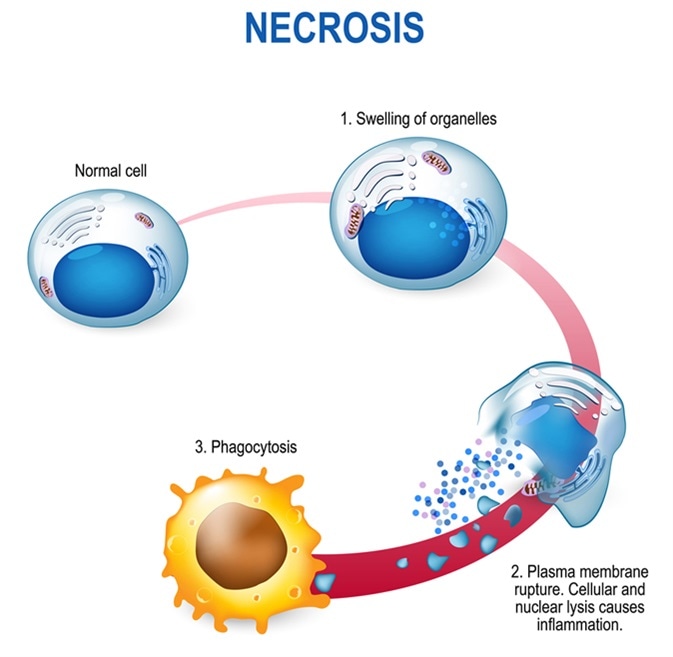

Necrosis - Pathologic Cell Death. Cell injury which results in the premature death of cells in living tissue. Image Credit: Designua / Shutterstock

On the other hand, necrosis is unprogrammed, or “accidental” cell death resulting from trauma, such as cellular damage or pathogen invasion. Following damage, the cell and organelles swell, leading to membrane rupture and internal components spilling into the surrounding intercellular space.

The Definition and Importance of Necroptosis

Recently, a new cell death method has been described, called necroptosis. This form of cell death is programmed, like apoptosis, but visually it looks a lot like necrosis, with membrane ruptures and swelling cells/organelles.

Understanding the pathways of necroptotic cell death

Necroptosis has been implicated in several types of disease, such as stroke, myocardial infarction, inflammatory bowel disease and cancer. It has also recently been investigated as a possible target for cancer treatment. Cancerous cells often resist cell death by avoiding apoptosis; therefore, if necroptosis could be specifically activated in cancerous cells, this resistance could be surpassed.

In a nutshell, necroptosis is carried out when apoptosis is inhibited. For example, the vaccinia virus possesses inhibitors of both caspase 1 and 8, which are required for apoptosis, and therefore without necroptosis this infection could avoid cell death. Therefore, this process is a highly controlled version of necrosis, with a very specific pathway, as described below.

Death Receptor-Dependent Process

The most common form of necroptosis activation is through the activation of death receptors.

- Initially, an extrinsic signalling ligand binds to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) or another death receptor.

- This subsequently leads to the recruitment of a complex, called the prosurvival complex I. This is composed of TNF-receptor-associated death domain (TRADD), polyubiquitinated RIPK1 and ubiquin E3 ligases.

- RIPK1 is then deubiquitinated and dissociates, forming either complex IIa or IIb. Complex IIa is involved in caspase 8 activation, which leads to apoptosis. Complex IIb, however, is involved in necroptosis and is formed when caspase 8 is inhibited. RIPK1 recruits RIPK3 and they phosphorylate each other. This then leads to oligomerization and necrosome formation.

- This necrosome then phosphorylates MLKL at a threonine and serine residue.

- MLKL then inserts into the membrane and permeabilizing it, which ultimately leads to necroptosis.

- The internal cellular components and DAMPs are then released, which trigger inflammation and the acquired immune response. Finally, the dead cells are cleared through the process of pinocytosis.

Death Receptor-Independent Processes

There are also additional methods which are not dependent upon death receptors. The first example of this is through activation of toll-like receptors (TLRs). These proteins are members of the innate immune system, functioning to recognise cellular stress. When they are activated, they bind to RIPK3, leading to necroptosis.

Additionally, DNA-dependent activation of interferon gamma (IFN) regulatory factors (DAI) can also trigger necroptosis. They bind to and recognise viral DNA, and thus stimulate necrosome formation. In the future, specific combination therapies that target these and other cell death modalities represent a promising strategy for treating critical illnesses.

Further Reading