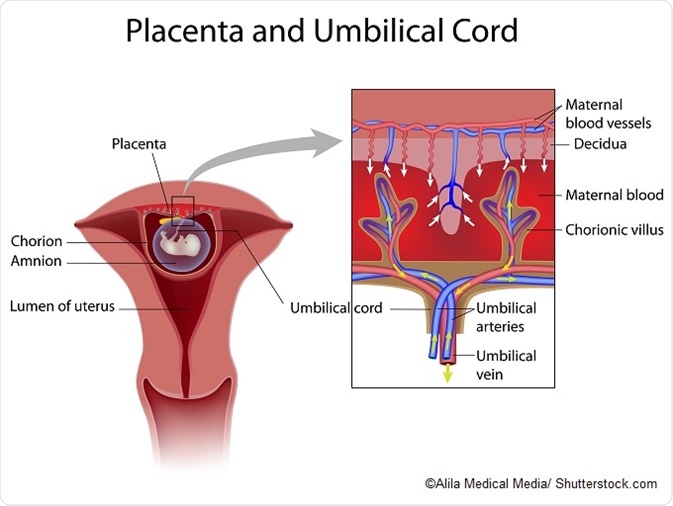

The placenta is an organ attached to the womb lining that supplies a developing fetus with nutrients and oxygen, as well as removing fetal waste and secreting hormones.

The microbiome refers to the trillions of microorganisms that reside within or on the human body. Microorganisms influence a number of bodily processes such as metabolism and digestion and are suspected to play a role in important illnesses such as diabetes and obesity. Although the microbiomes of various different body sites have been well-characterized recently, the placental microbiome remains somewhat a mystery.

Previous studies detailing the composition of the amniotic sac and intestine of newborn babies during their first week of life have suggested that microbiota are established and functioning long before a baby is born, but comparatively little had been published about the placental microbiome until fairly recently.

In 2014, Kjersti Aagaard and colleagues from Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital published a study examining the placental microbiome. The research was part of a broader initiative across the scientific community to explore the microbiome.

To investigate whether links exist between the composition of the placental microbiome and fetal development, the researchers performed genetic sequencing to characterize populations of bacteria in 320 placenta samples taken from preterm and full-term infants. The findings were compared with existing information on microbiota from the vaginas, intestine, mouths, airways and skin of women who were not pregnant.

Aagaard and team discovered a small community of microbes that was unique to the placenta. Metagenomic sequencing showed that certain bacteria in the placenta were abundant compared with other areas of the body, with E.coli being the most abundant. The placental microbiome most closely resembled that of the mouth and not the vagina, skin, gut or other body parts.

Species such as Neisseria, which is known to be part of the oral microbiota, were found to be abundant in the placenta. The researchers suggest that the microorganisms may move from the mother’s mouth to the placenta via the bloodstream, which is an interesting possibility, given the correlation that has been established between gum disease and preterm births. It also upends a previous hypothesis that microorganisms in the placenta originate in the vagina.

The researchers also found differences in placental microbiome composition between preterm births (around 34 to 37 weeks) and full term births. For example, there was an abundance of the proteobacteria Burkholderia in the placentas of mothers who had a preterm birth, while the endospore-forming bacteria Paenibacillus was highly prevalent in the placentas of mothers who gave birth at full term.

The authors suspect that a certain combination of bacteria in the placenta may be a contributory factor to preterm births and that the study may also help to explain why periodontal disease in pregnant women is associated with an increased likelihood of preterm births. The findings also point to a need for further research into the effects of women taking antibiotics while they are pregnant.

In addition, if the findings are confirmed by further research, this may be reassuring to women who give birth or plan to give birth by C-section, as some experts have claimed that children born this way fail to acquire the beneficial bacteria that babies are exposed to when delivered via the birth canal.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jul 19, 2023