Origin of cell lines – a woman named Henrietta Lacks

Image Credit: Koliadzynska Iryna/Shutterstock.com

Today, cell lines derived from animals including humans are grown and used for research in laboratories around the world. These cells can continuously divide given the right growth conditions.

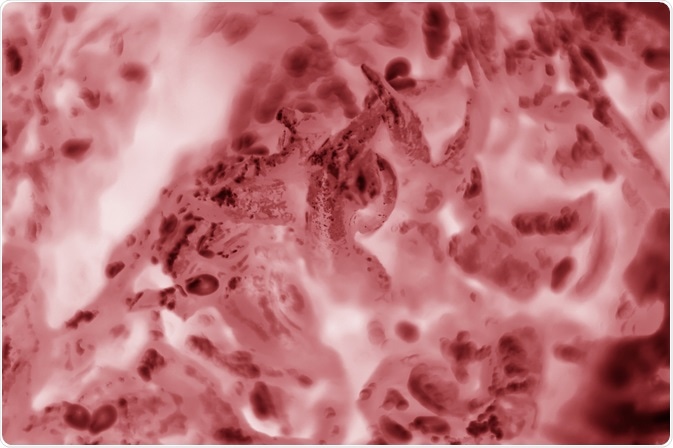

The first of these cell lines to be established is known as “HeLa cells”. This is a cell line established from a young African American woman named Henrietta Lacks who died of an aggressive cervical adenocarcinoma in 1951.

She presented to the gynecology department of Johns Hopkins hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, where they found the tumor on her cervix. When a biopsy was taken from the tumor, one specimen was given to George Gey and his colleagues at the Tissue Culture Laboratory at Johns Hopkins, who had ambitions to isolate and maintain normal or diseased tissue as “temporary or stable organoids or as derived cell strains”.

What made Henrietta Lacks’ tumor different from other tumors that had been brought to the laboratory was that the cells grew robustly. Before this, it was possible to grow cells from cancer specimens, however, these usually did not last and died before studies could be completed.

In contrast, this to the cells that grew from Henrietta Lacks’ tumor kept on dividing if the appropriate growth conditions were met. Initially, this was provided by using a medium composed of chicken plasma, bovine embryo extract, and human placental cord serum in a continuous “roller-tube culture”.

Out into the world – fighting polio and beyond

HeLa cells and the roller-tube culture method were used in the fight against the poliovirus. Previously, the poliovirus was grown in nervous system tissue, but George Gey successfully managed to grow the poliovirus in HeLa cells, and this system was then utilized by John Enders and colleagues. Then, in 1954, Jonas Salk also used HeLa cells to grow the poliovirus, and this led to the development of the Salk polio vaccine.

This was just the start of the use of HeLa cells as an important tool in research. HeLa cells were used for other research projects, from the search to identify the causative agent of AIDS, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the 1980s to modern “-omics” studies: genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics.

It is estimated that as many as 70,000 studies have been carried out using HeLa cells, including two who have been awarded the Novel Prize: in 2008 for the discovery that the human papillomavirus (HPV) is a causative agent of cervical cancer, and in 2009 for the discovery of the telomerase enzyme, which protects the telomeres of the chromosome, thus preventing the degradation of the chromosome.

Contamination?

After HeLa cells were established as an immortal cell line, samples were sent by George Gey to other scientists in the US and beyond. Due to its robust nature, HeLa cells were subsequently proliferated in many laboratories around the world. However, from the 1960s onwards, there were reports that HeLa cells can contaminate other cell cultures. Initially, the reports showed inter-species contamination as this is easier to detect.

In 1967 a report was published that showed intra-species contamination with HeLa cells. This was determined by Stanley Gartler, who used isoenzyme analysis, by analyzing the electrophoretic polymorphisms of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and phosphoglucomutase of 19 cell lines.

A variant of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, “type A”, is found predominantly in the African American population, and when put together with the phosphoglucomutase variant seen in these cell lines the results suggest that all cell lines were of the same origin.

Of course, HeLa cells are not the only case of cell culture contamination. A study found that what was thought of as human breast cancer cell lines were contaminated with both inter- and intraspecies cells, while other cells reported to be human were in fact of animal origin, and others reported to be from gibbons were found to be human. This is still an ongoing issue in tissue culture to this day.

So why were HeLa cells able to outcompete other cell lines? – there is a possibility that as samples of HeLa cells moved out of the original laboratory and began to be proliferated in many other laboratories, its ability to robustly grow was selected for even more as they were continuously grown. Thus, HeLa cells could have inadvertently been selected to be able to outcompete other cell lines.

Sources

Lucey, B. P et al. (2009) Henrietta Lacks, HeLa Cells, and Cell Culture Contamination. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine www.archivesofpathology.org/.../1543-2165-133.9.1463

Immunology.org. HeLa cells (1951). https://www.immunology.org/

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 23, 2023