Introduction to dendritic cells

Function of dendritic cells

Dendritic cells and diseases

Dendritic cells and diseases

References

Further reading

Introduction to dendritic cells

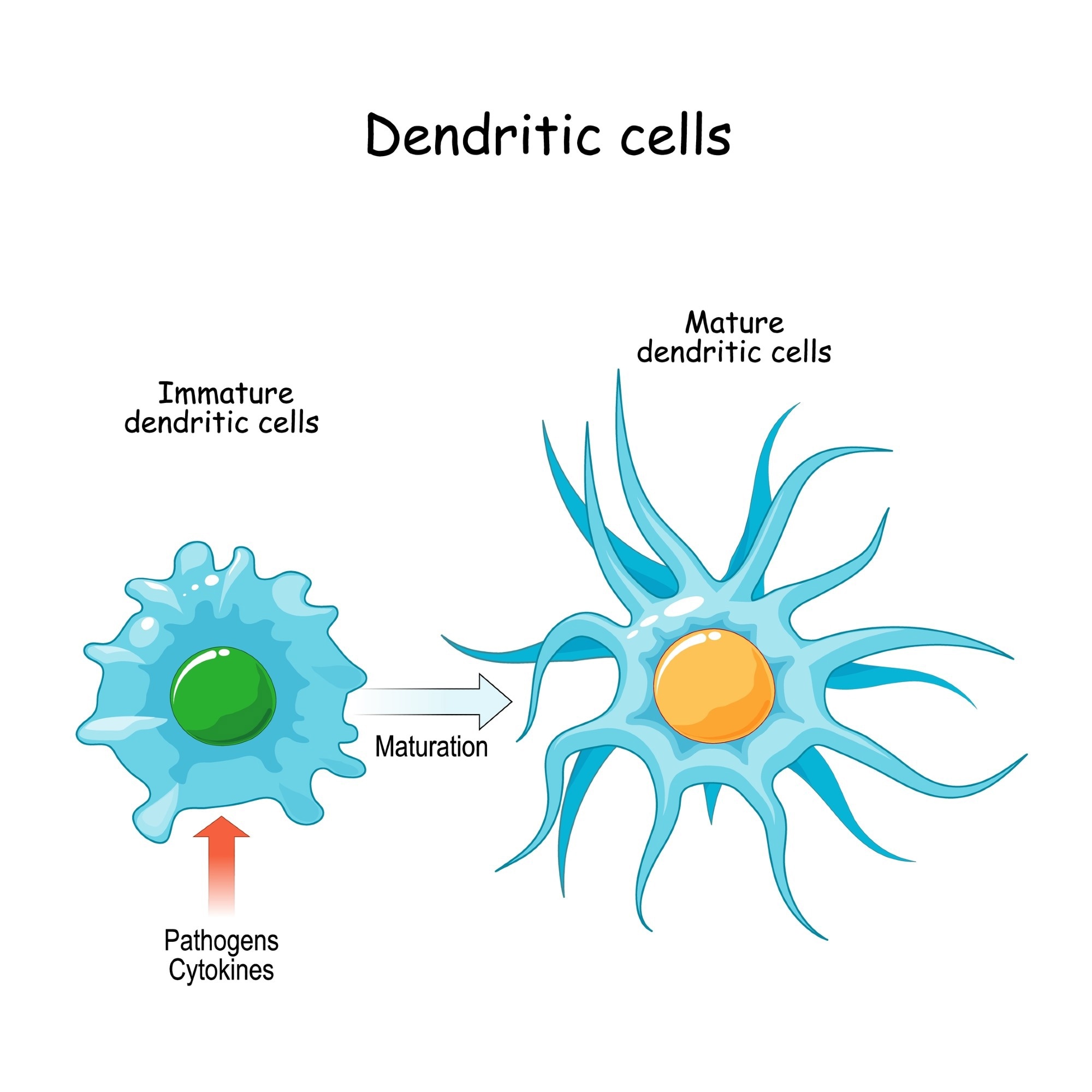

Dendritic cells (DC) are a type of antigen-presenting cell (APC) that play an essential role in the adaptive immune system. The primary function of DCs is to present antigens and the cells are therefore sometimes referred to as “professional” APCs. Dendritic cells are so named because during development, they develop branched projections called “dendrites” to maximize their surface area and increase exposure to antigens.

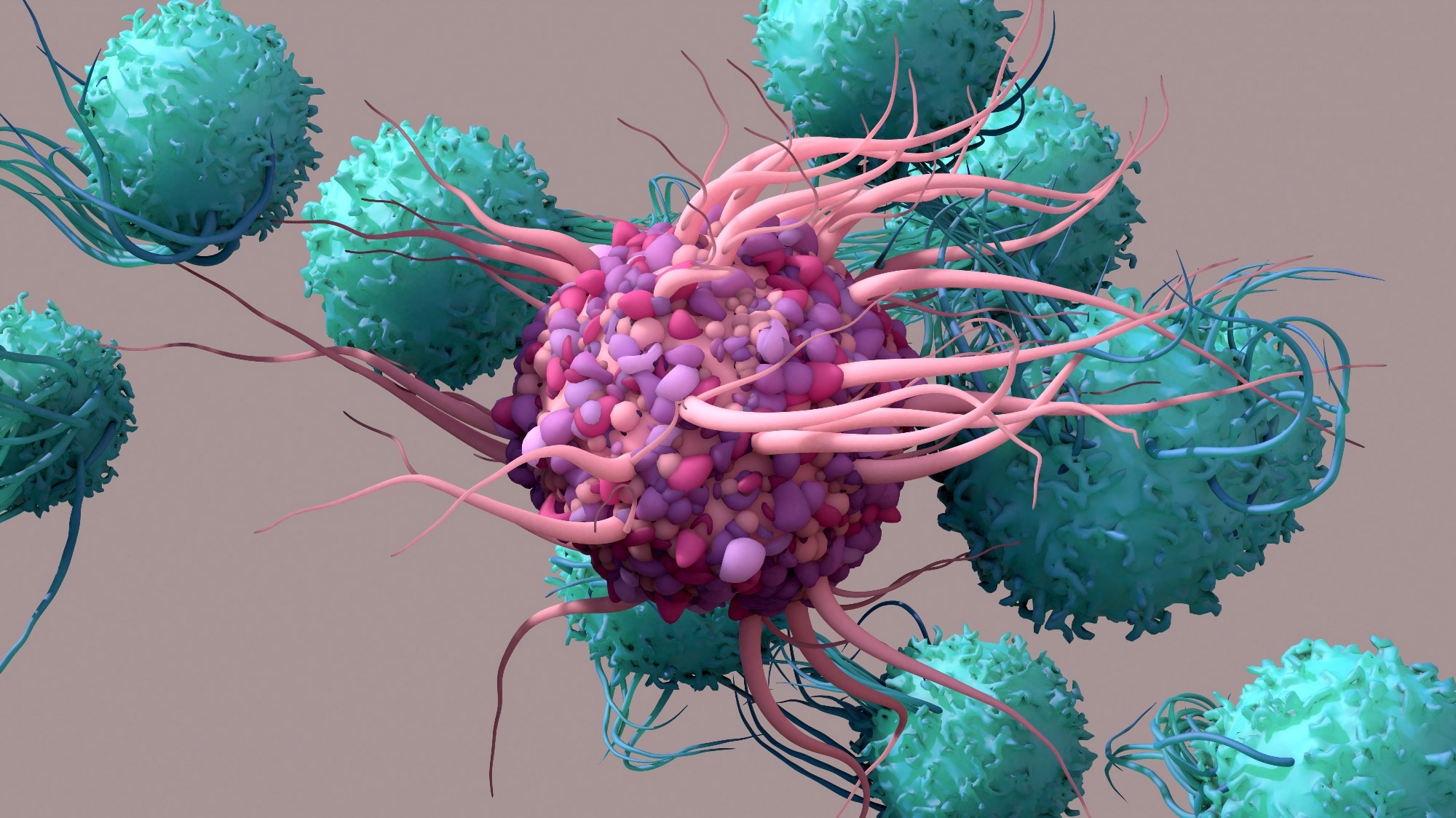

Dendritic Cell activate T cells, trigger immune responses. Image Credit: Design_Cells / Shutterstock

Dendritic Cell activate T cells, trigger immune responses. Image Credit: Design_Cells / Shutterstock

Dendritic cells are found in tissue that has contact with the outside environment, such as lung mucosa, epithelial cells of the skin, and the linings of the nose and the gastrointestinal tract. These regions form the interface between the body and the environment and are constantly exposed to foreign proteins and pathogens. Immature forms of DCs are also found in the blood. Once activated DCs move to the lymph tissue to interact with T and B cells and help shape the adaptive immune response. In the intraepithelial tissue of the respiratory system, they can be found in very high densities (500 – 1,000 cells per mm2). Their densities depend on the level of antigen exposure, being highest in the proximal airways and decreasing towards the distal airways and alveoli.

Ralph Steinman first described dendritic cells in the 1970s. He found these cells in the spleen, and it was later discovered that the cells were present in all lymphoid and most non-lymphoid tissues. Before this, immunologists generally thought that macrophages were the main APC in the immune system. Compared with DCs, macrophages were present in more significant numbers, were evenly spread throughout the body, and were known to present antigens. However, as DCs were relatively rare, it took until the 1980s for them to become accepted as professional APCs.

While all DC subpopulations are capable of antigen uptake, processing, and presentation, they differ based on origin, function, location, and response to inflammation or infection. The myeloid DCs differentiate from monocytes and macrophages in the presence of cytokines such as granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukins (IL) and express myeloid-specific markers. Plasmacytoid DCs resemble plasma cells and do not express myeloid markers. Their primary role is thought to be in response to viral infections, where they produce large amounts of type I interferons. The DC subpopulation in epithelial tissues is known as Langerhans cells, expressing E-cadherin, Langerin, and Birbeck granules.

Dendritic cells. Image Credit: Designua / Shutterstock

Dendritic cells. Image Credit: Designua / Shutterstock

Function of dendritic cells

Dendritic cells found in mucosal membranes are in a phenotypically steady state where they are primed for antigen uptake but are not adept at presenting these antigens to T cells. Antigen uptake occurs via either micropinocytosis or micropinocytosis, depending on the size of the soluble antigen particles. A more efficient form of antigen uptake is receptor-mediated endocytosis, where specialized receptors, such as C-type lectin receptors, mannose receptors, and even apoptotic body receptors, are present on the DC cell surface and recognize and bind to their target antigens.

Following antigen uptake, their morphology and expression of cell surface markers changes, initiating maturation and migration to lymph nodes where these antigens are presented to T lymphocytes via multiple histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. The type and function of the DCs determine whether the initiated immune response is cytotoxic T cells, T-cell tolerance, memory B-cells, or polarized T-helper (Th) cells. The foreign and pathogen-derived proteins are partially-degraded in the endosomes, lysosomes, cytosol, and endoplasmic reticulum of the DCs using various hydrolases and cathepsins and presented as antigenic peptides on MHC class I and class II molecules on the DC cell surface.

The antigens presented to T cells on MHC class 1, and class II molecules will activate and induce the T cells to become cytotoxic T cells or helper T cells, respectively. Dendritic cells further enhance the immune response by presenting ligands on their surface, which bind to the T cells’ costimulatory molecules. Various types of cytokines, such as IL-12, further stimulate and optimize T-cell proliferation. Antigens from endogenous sources such as viral proteins are generally presented on MHC class 1 molecules to initiate cytotoxic T cell proliferation, while extracellular antigens are presented on MHC class II molecules. While other immune cells, such as macrophages and B cells, are also involved in antigen presentation, DCs are versatile because of their ability to “cross present.” Dendritic cells can present extracellular antigens on MHC class I molecules, initiating cytotoxic T cell proliferation.

Dendritic cells also contribute to the function of B cells and help maintain their immune memory. Dendritic cells produce cytokines and other factors that promote B cell activation and differentiation. After an initial antibody response has occurred due to an invading body, DCs found in the germinal center of lymph nodes seem to contribute to B cell memory by forming numerous antibody-antigen complexes. This provides a stable source of antigen that the B cells can take up themselves and present to T cells.

Immune tolerance is another function that DCs carry out, along with responding to infections, inflammations, and foreign pathogens. Dendritic cells constantly present self-antigens and non-pathogenic antigens to T cells, inducing the production of immunosuppressive regulatory T cells (Tregs).

Dendritic cells and diseases

Various respiratory diseases and disorders are associated with rapid changes in the number of dendritic cells in the mucosa of the airways and lungs. For example, in allergic asthma, the number of myeloid DCs in the blood drops as they are diverted to the lungs to launch an immune response. In allergic rhinitis, long-term low-dose allergen exposure increases the number of plasmacytoid DCs in the nasal mucosa. Changes in the number of DCs in respiratory mucosa have been observed in other diseases such as pneumonia and bronchiolitis, and following lung transplant and cigarette smoking.

The ability of DCs to induce immune tolerance presents a hurdle to developing antitumor immunity in cancer since most tumors are quite similar to normal cells in terms of the antigens they present. With tumor progression, factors in the tumor microenvironment can induce DCs to present ligands such as Programmed-Death ligands (PD-Ls) that cause T cell death and transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) for Treg production, as well as cytosolic enzymes that generate immunosuppressive metabolites.

Understanding the role of optimal vaccine adjuvants, which are often DC maturation signals, and the different maturation pathways that DCs exhibit based on the pathogens encountered and ligands received could aid in developing better cancer immunotherapies.

Dendritic cells

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Sep 5, 2022