The endometrium is the inner lining of the uterus and consists of many layers of cells, both gland cells and stromal or supporting cells. When the endometrium becomes thickened it is called endometrial hyperplasia.

The term covers a lot of conditions, however, because thickening can refer to anything from a simple thickening due to estrogen exposure, which quickly reverses once the estrogen is removed, to a thick and abnormal endometrium which could develop into cancer of the uterus.

Endometrial hyperplasia has been classified in numerous ways but all of them agree on the need to treat the hyperplasia once it reaches the top end of the spectrum, with atypical cells and very crowded cells, and with the glands being wavy, branching and budding. Early changes are typically found in only one polyp, but later advanced changes are seen throughout the endometrium.

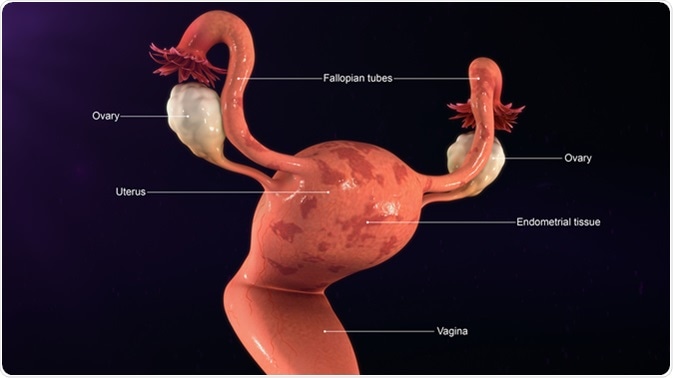

Endometrial Tissue 3d illustration. Image Credit: Sciencepics / Shutterstock

WHO Scheme

The earlier WHO classification has now given way to a more clinically relevant scheme:

- Hyperplasia without atypia: simple or complex, with an incidence of 5% in premenopausal women without symptoms

- Hyperplasia with atypia: simple or complex, with an incidence of 1%, also called endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN)

The drawback is that while atypia is rightly given a prominent place in the classification, the architecture of the glands has been largely sidelined. Another system of classification divides the lesions into either benign hyperplasia or endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia, which is considered a precancerous lesion with a high chance of becoming malignant within a few years.

Risk Factors

The risk factors for endometrial hyperplasia are:

- High education

- Obesity especially weight over 90 kg

- Diabetes mellitus type 2

- Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) with too low or absent progesterone dosage

- A tumor producing estrogen or androgen

- Age 45 years or less

- Infertility

- Family history of carcinoma of the colon

- Never having had a baby

- Chronic anovulation such as the polycystic ovarian syndrome

- Obesity with metabolic syndrome due to increased peripheral conversion of androgens produced in the ovary to estrogens

It rarely occurs in postmenopausal women unless they are on hormone replacement therapy with estrogen alone.

The mechanism of endometrial hyperplasia is sustained stimulation by estrogen without counterbalancing progesterone exposure, stimulating the proliferation of endometrial gland cells.

Outcome

Hyperplasia without atypia is considered likely to regress with progesterone, removing estrogen exposure.

However, up to 40 of every 100 women with complex atypical hyperplasia have an occurrence of endometrial cancer already elsewhere in the endometrium. The risk of cancer developing is very high in the remaining 60% as well. In fact, about 85% of endometrial cancers are endometrioid carcinomas i.e., cancers which closely resemble normal but highly thickened endometrium, without much invasion of the underlying uterine muscle, and depending upon estrogen for its growth. These are much more common in women who have been diagnosed to have atypical hyperplasia, especially of the complex type.

Diagnosis and Treatment

The diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia is by biopsy or curettage of the uterine endometrium. Biopsy refers to the removal of a sample of tissue to examine it under the microscope. However, the risk of missing a cancerous lesion is quite high, and therefore precancerous lesions, i.e., atypical endometrial hyperplasia, are generally treated by the complete removal of the uterus, or total hysterectomy.

Hyperplasia without atypia is benign and is treated conservatively, by progesterone to reverse the action of unopposed estrogen, and reducing exposure to estrogen as by weight loss, metformin use, or oral contraceptives. The risk of cancer is low, about 1-3%, and only if the estrogen exposure continues long-term.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 26, 2019