Introduction

Transmission

Symptoms

Pathogenesis

Diagnosis and treatment

The history of smallpox vaccination

Modern smallpox vaccines

Conclusions

References

Further reading

Introduction

Smallpox is considered one of the greatest epidemic disease scourges in human history. Smallpox has been feared for centuries due to its deadly nature, high transmissibility, and lifelong disfigurement.

Smallpox is an acute infectious disease caused by the variola virus. The term “smallpox” was initially introduced in Europe in the 15th century and is also known by the Latin names “Variola” or “Variola vera,” which is derived from the Latin words varius or varus, which mean “stained” or “mark on the skin,” respectively. The word ‘poc’ or ‘pocca’ refers to a bag or pouch describing an exanthematous disease.

Infection with the variola virus can manifest in two clinical forms, including variola major and variola minor, both of which can be transmitted following prolonged face-to-face contact between people. Infection with variola major is more severe than that with variola minor, with case fatality rates (CFRs) of 30% and less than 1%, respectively.

The origin of smallpox is unknown; however, reports indicate that the disease originated in Egypt and India.

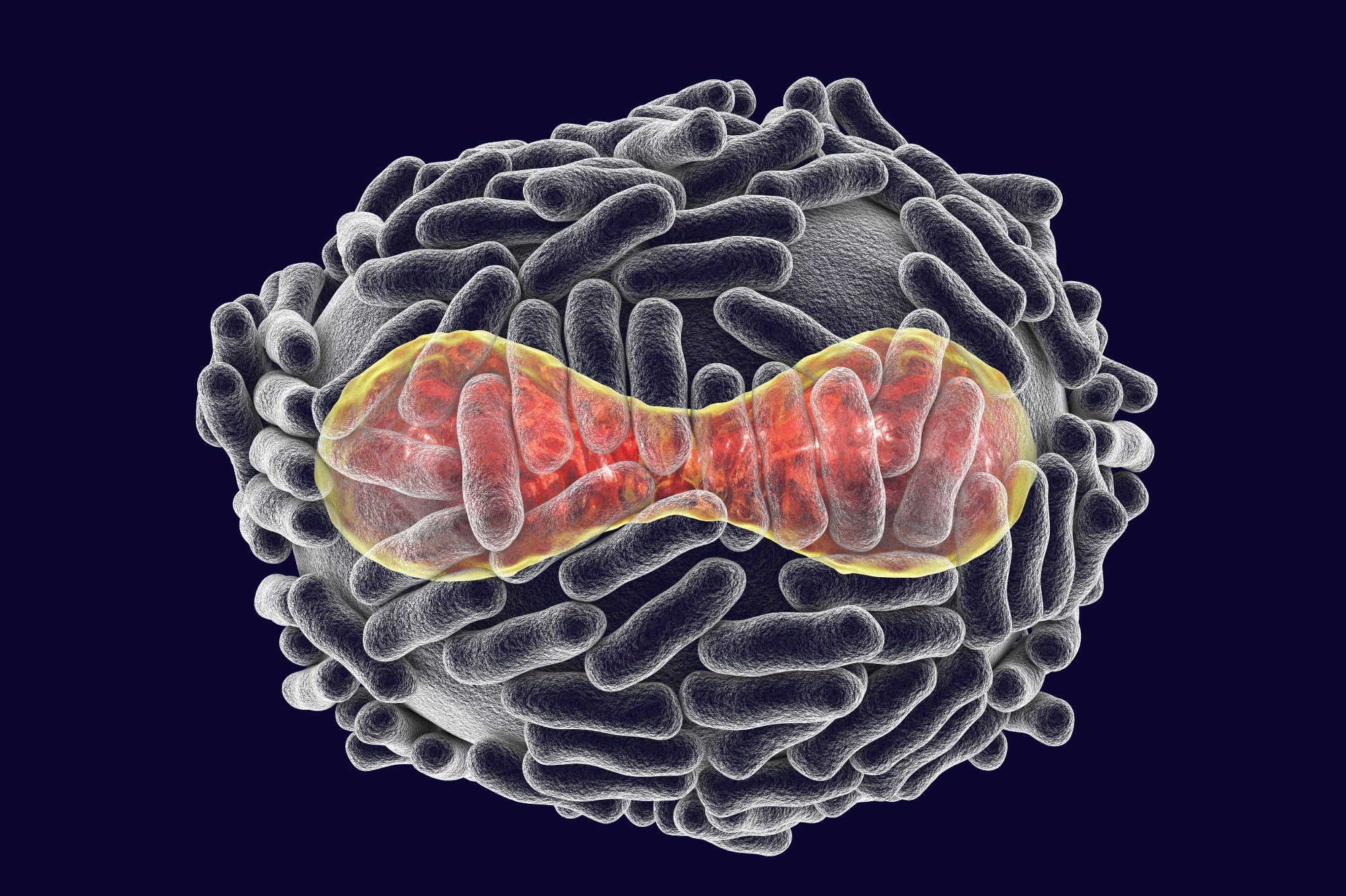

Variola virus, a virus from the Orthopoxviridae family that causes smallpox, a highly contagious disease eradicated by vaccination, 3D illustration. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

Transmission

Human-to-human transmission of variola virus occurs by inhalation of oropharyngeal droplets from an infected person when they cough or sneeze. Smallpox patients are considered infectious from when the first oropharyngeal lesions appear, throughout the course of the disease, and until the last scab falls off the body. Therefore, an individual is considered at risk of contracting smallpox after prolonged and close contact with an infectious smallpox patient.

Smallpox transmission can also occur following exposure to material such as bedding and clothing used by an infected individual, particularly following contact with their pustules or crusted scabs. Rare reports of airborne transmission in hospital and laboratory settings have also been described. Zoonotic transmission of smallpox has not been reported.

Symptoms

The average incubation period of the smallpox virus is 10 to 14 days. Initially, an infected individual presents prodromal symptoms such as a high fever between 38.3°C and 40.5°C, malaise, headaches, and back pain. As the fever subsides, lesions will initially develop in the oropharynx as erythematous spots on the tongue and sores in oral mucous membranes.

As the sores break down, a characteristic skin rash develops that may affect the face and extremities, ultimately spreading to the trunk, palms, and soles in a centrifugal pattern. Smallpox lesions develop uniformly throughout the course of the disease and progress from macules to papules to vesicles over the course of four to five days.

Within another one or two days, vesicles will often umbilicate and evolve to pustules that are round, tense, firm to the touch, and deep-seated within the dermis. Lesions typically exhibit the same stage of development in any area of the body at any given time.

This 1973 image depicts the dorsum of a Bangladeshi smallpox patient’s right hand, revealing the numerous umbilicated maculopapular lesions which are characteristic of this viral illness.

Crusting and scab formation typically begins by the ninth day of exanthema, with the crusts sloughing off around 14 days after the onset of the rash.

Pockmarks and scarring, especially on the face, are the most common sequelae resulting from virus-mediated necrosis and destruction of sebaceous glands. Although rare, blindness can arise due to corneal scarring following keratitis or corneal ulcerations. Smallpox can range in severity from relatively mild to very severe types with a high likelihood of fatal outcomes. Ordinary type smallpox has been observed in most cases.

Typically, mild cases of smallpox, which may also be described as the ‘modified-type,’ arise in previously vaccinated individuals. Conversely, more severe cases may be referred to as ‘flat-type/malignant and ‘hemorrhagic-type’ and are seen in those with predisposing immunocompromising conditions, especially among pregnant women.

Life-threatening complications associated with smallpox include blood loss, toxemia, cardiovascular problems, and/or secondary bacterial infections.

Pathogenesis

Inhalation of the variola virus initiates foci of mucosal infection in the upper airway without causing symptoms or apparent lesions. According to the mousepox model, replication at the point of entry is followed by infection of mononuclear phagocytic cells in regional lymph nodes, with the potential further spread through the bloodstream to similar cells in the liver, spleen, and other tissues.

After reaching the skin, the virus spreads in the middle and basal layers, causing expanding zones of necrosis that form vesicles. In the nonkeratinized squamous epithelium of the oropharynx, the same process is responsible for the formation of ulcerated lesions.

Pustules with surrounding edema and erythema are produced as a result of increased permeability of local blood vessels and the subsequent infiltration of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages. The cell-mediated immune response is a prerequisite for lesion resolution.

The ability of host responses to limit viral replication during the incubation period correlates directly with disease severity. Once viral dissemination has occurred, manifestations of severe illness, including hypotension and coagulopathy, develop due to host inflammatory responses. Thus, differences in host responses are responsible for a spectrum of diseases.

Diagnosis and treatment

According to United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the primary diagnostic criteria for smallpox include febrile prodrome one to four days before rash onset, with a fever exceeding 38.3 °C. In addition, headache, backache, chills, vomiting, and severe abdominal pain are also often present in infected patients.

Classic smallpox lesions are deep-seated, firm/hard, round, well-circumscribed vesicles or pustules. As they evolve, lesions may become umbilicated or confluent.

Minor diagnostic criteria for smallpox include centrifugal distribution of the rash. The patient appears moribund or toxic, with slow rash evolution from macules to papules to pustules over days, as well as lesions on the palms and/or soles.

CDC laboratory criteria for confirming the diagnosis of smallpox include the identification of variola deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) in clinical specimens through the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay. Variola virus may be isolated from clinical specimens and cultured in a biosafety level 4 (BSL4) laboratory. Electron microscopy may also be utilized.

Antiviral medications such as tecovirimat (TPOXX) and brincidofovir (TEMBEXA) were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for smallpox in July 2018 and June 2021, respectively. Cidofovir has also been shown to stop the growth of the variola virus; however, it is not currently approved by the FDA to treat smallpox. Supportive measures include antibiotics for secondary bacterial infections and/or medications for pain or fever.

The history of smallpox vaccination

The basis for vaccination against smallpox began in 1796 when Dr. Edward Jenner noticed that milkmaids who had been infected with cowpox were protected against smallpox. Jenner was also aware of variolation, which involves infecting people with low doses of smallpox to induce natural immunity against the virus in the event of future reinfection.

Edward Jenner. (2022, September 19). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Jenner

Edward Jenner. (2022, September 19). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Jenner

Thus, Dr. Jenner hypothesized that exposure to cowpox could similarly confer protection against smallpox. To test his theory, Dr. Jenner took material from a cowpox sore on a milkmaid’s hand and inoculated it into the arm of James Phipps, the nine-year-old son of Jenner’s gardener.

Several months later, Jenner exposed Phipps several times to the variola virus; however, Phipps never developed smallpox. By 1801, Jenner published “On the Origin of the Vaccine Inoculation,” wherein he summarized his observations and expressed hope that “the annihilation of smallpox, the most dreadful scourge of the human species, must be the final result of this practice.”

Vaccination became widely accepted and gradually replaced the practice of variolation. At some point in the 1800s, the virus used to make the smallpox vaccine changed from cowpox to vaccinia.

By 1967, when the Intensified Eradication Program began, smallpox was already eliminated in North America and Europe. However, smallpox cases were still reported in South America, Asia, and Africa.

As the efforts of this program continued, smallpox was eventually eradicated from South America by 1971, followed by Asia and Africa in 1977. Finally, on May 8, 1980, the 33rd World Health Assembly declared that smallpox was globally eradicated.

Modern smallpox vaccines

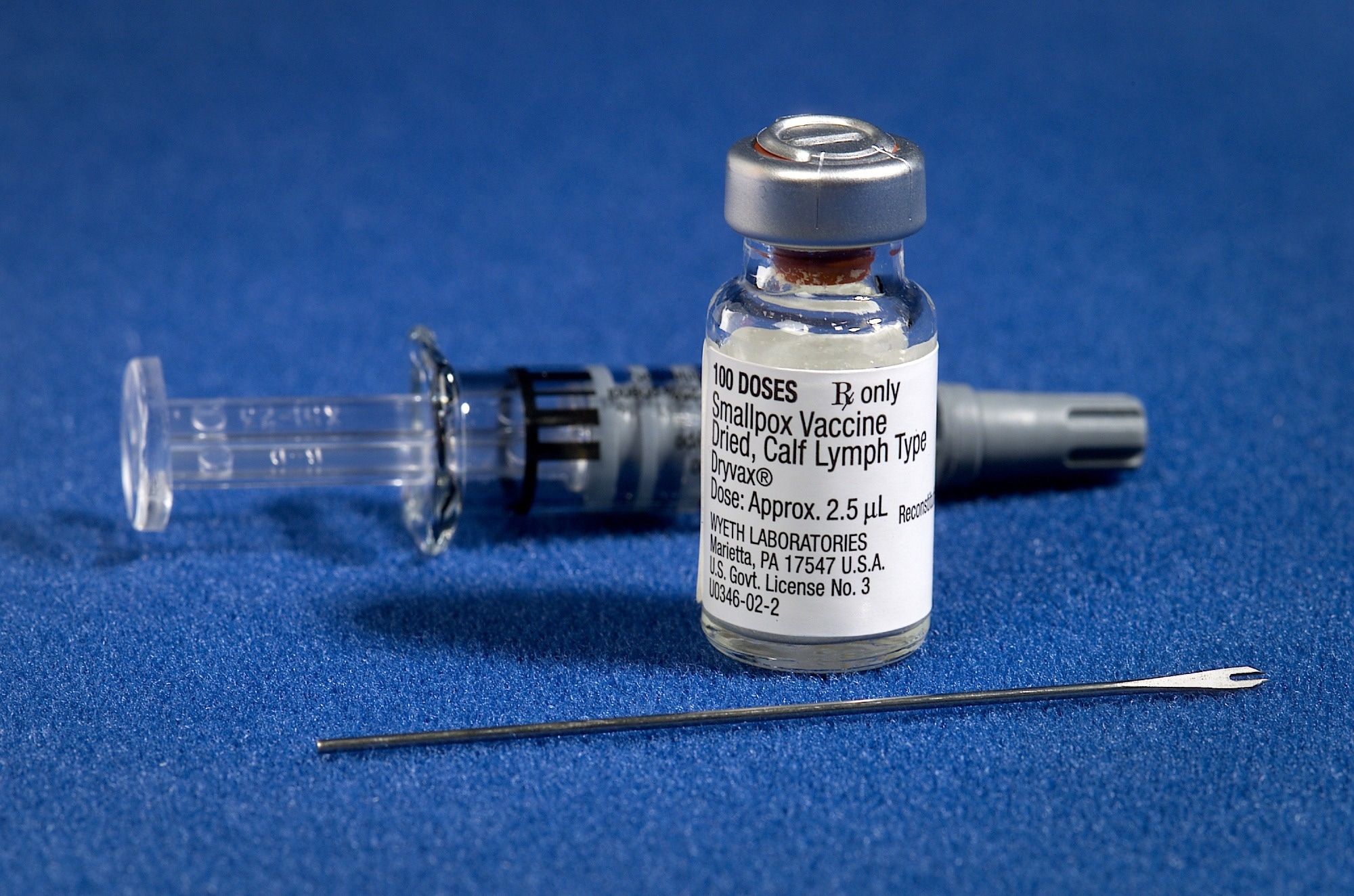

The eradication of smallpox led most western countries like the United States to stop the routine vaccination against this virus in the 1970s. However, the U.S. has three smallpox vaccines in its Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) in the event of an emergency, such as the 2022 global monkeypox outbreak.

The three smallpox vaccines in the SNS include ACAM2000, Aventis Pasteur Smallpox Vaccine (APSV), and JYNNEOS. Whereas ACAM2000 and JYNNEOS are licensed smallpox vaccines in the U.S., APSV is an investigational vaccine that can only be used during a public health emergency.

"Smallpox vaccine." Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 16 Sept. 2022, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smallpox_vaccine. Accessed 21 Sept. 2022.

"Smallpox vaccine." Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 16 Sept. 2022, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smallpox_vaccine. Accessed 21 Sept. 2022.

Both ACAM2000 and APSV are replication-competent smallpox vaccines that contain the vaccinia virus, which is a poxvirus similar to smallpox but less harmful. Compared to ACAM2000 and APSV, JYNNEOS is an attenuated live virus vaccine specifically indicated for individuals with certain immune comorbidities, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or atopic dermatitis.

Conclusions

Smallpox is an acute, contagious, and often fatal disease caused by the variola virus that presents with characteristic clinical signs and symptoms. Despite being eradicated worldwide since the 1970s, zoonotic poxviruses, such as the monkeypox virus, could also emerge in humans.

Thus, the development and availability of rapid, sensitive, and specific diagnostic techniques for identifying and differentiating orthopoxviruses remain essential. Further research on orthopoxviruses is also needed to assess the evolutionary characteristics of these viruses to improve global preparedness and prevent the devastating impacts of viral outbreaks in the future.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Sep 20, 2022