Resistance to external pathogens by an organism’s immune system has been strongly debated by life scientists for many years. Mainly observed in plants, antibody-mediated pathogen resistance is achieved when the expression of certain antibodies or antibody fragments causes the external pathogen to be inactivated via antibody attachment.

Plant-Based Pathogen Resistance

Plant diseases have a major impact on global food systems – with crop yield being severely affected by infections that spread throughout the field. With food shortages gripping the modern world, attention has been drawn to the genetic modification of plants grown for consumption – otherwise known as genetically modified organisms (GMO).

Some modifications of crop-plant genomes include increasing drought resistance, so that certain crops can be grown in arid environments. Another example includes golden rice – a strain of rice that was created by the insertion of a certain gene from the daffodil genome (Narcissus species), which subsequently increased the vitamin A content within the new strain of rice, via β-carotene. This was done in response to a country-wide vitamin A deficiency in China.

With all these adaptations improving crops around the world, attention was recently bought to the possibility of reducing or entirely eradicating plant diseases, through the manipulation of certain plant genes that produce antibodies that target external pathogens.

For example, recombinant antibodies can be used to target plant pathogens – with ectopic expression of these antibodies in plants interfering with the development of the target pathogen at a specific point in the pathogen’s life-cycle.

This method of improving plant disease resistance was originally used to target plant viruses but has recently been involved in the prevention of other plant diseases, as well as in effecting the proteins involved in plant-pathogen interactions.

Intracellular Pathogen Resistance

At the beginning of the 20th century, the great debate of humoral and cellular immunity was becoming more prominent in the world of life sciences. The humoral immune system relies strongly on the production of relevant antibodies to provide a successful immune response; whereas the cellular immune system consists of different cell types, including T-killer cells, monocytes, etc.

Scientists that were seen to mainly support the humoral immune system as being the largest component of the entire vertebrate immune system, gave the argument that vertebrate immunity was conferred by substances in the blood which were soluble, as well as an effective response by the body’s naturally produced antibodies. They concluded that the function of phagocytotic cells within the bloodstream mainly cleared microbial debris from the body.

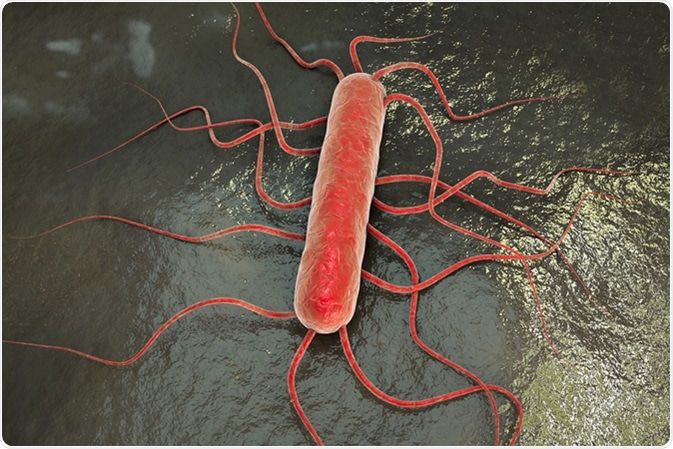

In the 1960’s, multiple studies had been performed using a variety of eternal pathogens. For example, a study involving Listeria monocytogenes proved that the infected organism required an effective cellular immunity in order to control the spread of infection. This response is mediated by granuloma formation, as well as the contribution of T-lymphocytes. With Listeria monocytogenes being a facultative intracellular pathogen, this proved (alongside other studies) that for the most part, the humoral immune system was most responsible for providing an immune response – however, a cellular response is required for pathogens that act in a facultative, intracellular manner.

3D illustration of bacterium Listeria monocytogenes. Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock

After just under 100 years of scientific research into the inner workings of the vertebrate immune system, one can conclude that an efficient immune response depends on certain factors – including the health of the infected organism themselves, as well as the type of pathogen causing the infection and the pathogenicity of the infection. The plant immune system, however, has been repeatedly proven to require an antibody-mediated response for an efficient immune response – with genetic research and adaptations to the relevant plant genomes further proving this.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jun 17, 2023