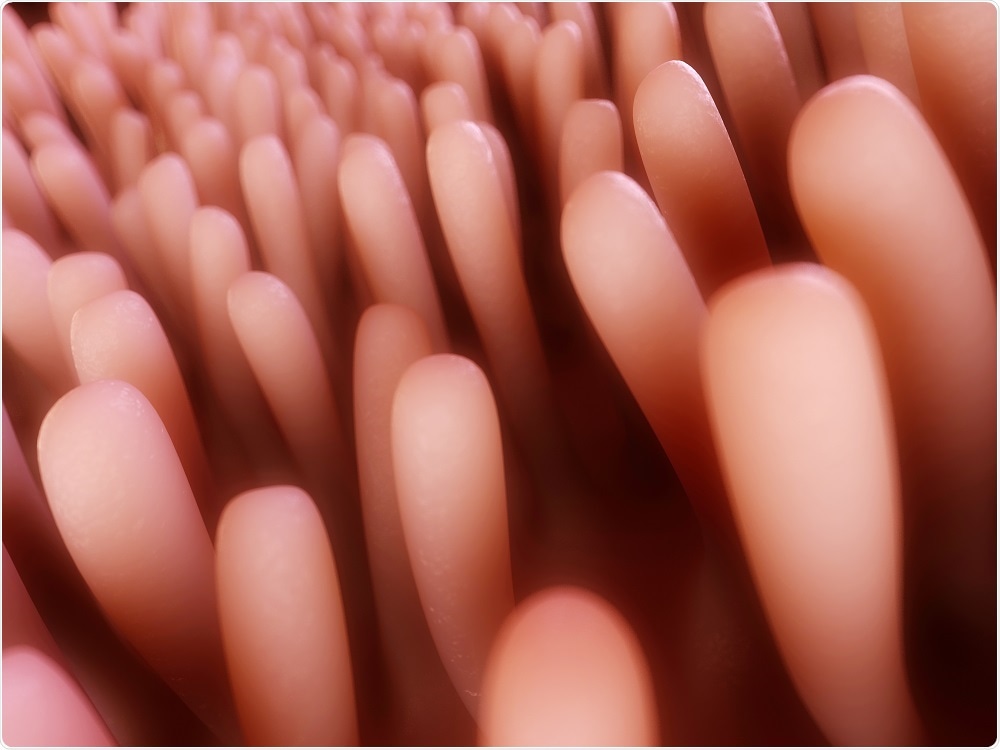

Enteroids are a type of organoid obtained from the small intestine. They allow researchers to study the normal physiology of the cells within the small intestine, and the efficacy of novel medicinal compounds.

Image Credit: Sebastian Kaulitzki / Shutterstock

Image Credit: Sebastian Kaulitzki / Shutterstock

Organoids are small and simple models of organs, allowing ex vivo organ manipulation and investigation. Intestinal stem cells (ISCs) are propagated to form three-dimensional mini-intestines, giving scientists insights into cellular processes such as gastrointestinal tract renewal, stem cell function, host-cell interactions, and the role of different cells within the intestine.

Biology of the gastrointestinal tract

The intestine is composed of many types of cell, which are constantly renewing due to the replication of ISCs and shedding of old cells. This ISC proliferation occurs at the bottom of pits within the epithelial wall, which are called “crypts”.

As the undifferentiated cells move up the crypts, they develop to produce highly differentiated progeny and replace the old epithelium. They initially develop into two different lineages (absorptive and secretory cells), and eventually specialise further into goblet cells, paneth cells, enterocytes, enteroendocrine cells, tuft cells, and microfold cells.

Investigating the gastrointestinal tract using enteroids

The properties of the gastrointestinal tract have previously been investigated through the use of several ex vivo models. Traditional ex vivo culture systems have several limitations as, compared with in vivo intestine cells, they have highly different microenvironments.

Recent progress has developed culture techniques which allow the growth and propagation of human ISCs into crypt structures that are highly similar to those of the human intestine. Growth factors are required for this process. These include; R-spondin-1, Wnt3a and EGF. These external miniature organs can then be used to further investigate the properties of the intestine.

These models are invaluable to research for several different reasons. They aid development of novel drugs by speeding up the research process and making it cheaper. These cells can also continue to propagate eternally, and have been shown to be stable for over 15 generations.

All of the different types of cells within the intestine are accurately replicated, allowing the highly accurate analysis of drug toxicity and cell interactions. Therefore, the use of enteroids has become the golden standard for research into intestinal function.

Applications of enteroids in research

One example of enteroid application within research is the study of Salmonella Typhimurium infection. This form of Salmonella leads to gastroenteritis in human hosts, but traditional methods of study are limited as this infection leads to highly different symptoms within murine models.

Therefore, enteroids provide an ideal model as they are very similar in structure to normal intestines and they are human-derived, and so respond in a similar way.

Enteroids have provided insight into many different stages of Salmonella Typhimurium infection, including invasion, the inflammatory response and the role of Paneth cells in defence. Many other infectious agents have also been investigated using enteroids, including Escherichia coli, rotavirus, norovirus and various parasites.

Another use of enteroids is research into the differentiation of intestinal lineages. Studies have revealed the complex role of the microenvironment “niche” within the differentiation of cells, and the production of both WNT and BMP signalling used to determine which cells are developed.

WNT leads to stem cell proliferation, whereas BMP leads to differentiation. These signalling compounds are produced from various sources, leading to the production of different types of cells in different locations. Using enteroids has enabled analysis of the contribution of different sources of signals.

Additionally, enteroids have been used to study the role of Na+ and Cl- absorption within the intestine. Impairment of this process is thought to be involved within the cholera toxin leading to diarrhoea. This has been further investigated within enteroids, identifying the transporter NHE3, which is inhibited by the toxin.

Overall, enteroids enable the investigation into disease, maintenance and function of the gastrointestinal tract, which is not possible in traditional ex vivo model systems. They can also continue to develop forever, increasing the rate of drug development and research.

This method is still premature and further research into their properties is required. However, these models are powerful and will hopefully aid the development of many drugs in the future.

Hans Clevers - Lab-grown human organs (organoids)

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 26, 2019