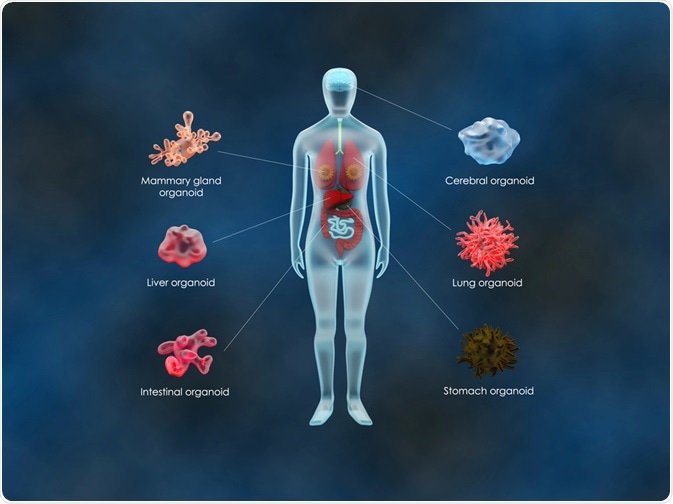

Organoids are a recent development in the field of life sciences which show real promise in helping push drug discovery and therapy into the future. This article will discuss a brief overview of the technology and some studies in the field.

Image Credit: Meletios Verras / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Meletios Verras / Shutterstock.com

What are Organoids?

Traditionally, the biomedical sciences have been constrained by the use of 2 dimensional cultures in research. These methods have been widely used since around the 1940s and have their advantages, being inexpensive and easy to use. However, 2D methods have inherent flaws such as lack of predictivity and the fact that they do not represent real cell environments.

Organoids allow for study of cellular lines in an ex vivo context. They are effectively tissue surrogates of multicellular fragments derived that can be used to study the effects on cell lines in real-time and in a context which more realistically mirrors what happens in living organisms.

Organoids are generated by culturing cells in a 3D extracellular matrix. This is typically Matrigel, and they are cultured under conditions which allow for self-organization. Self-organization occurs due to their capacities for self-renewal and differentiation. The cells used to construct organoids are derived from embryonic stem cells, tissues, or induced pluripotent stem cells.

Organoids have become a key component in medical research and have been reported to mimic kidneys, hearts, lungs, and many other organs over the last few years. Recent studies have attempted to integrate blood and immune system cells into them. The technology has progressed significantly since the early 2010s and was named one of the biggest scientific advancements of 2013 by The Scientist.

Disease modeling, patient-specific drug candidate validation, tissue engineering, and research into the relationship between disease and demographics have all benefitted from research involving organoids. Two-dimensional models of organoid culture generation have been explored over the past few decades by researchers.

3D Extracellular Matrices – A More Reliable Design for Organoid Cultures?

Even though organoids have their distinct advantages over 2D cell cultures, conventional methods of culturing them still have drawbacks. By using an extracellular matrix hydrogel, organoids are allowed space to develop in the presence of exogenous morphogens. One popular exogenous morphogen is Wnt3a.

According to a study published in Cell in August 2020, organoids embedded in a dome-shaped 3-dimensional hydrogel matrix benefit from increased size heterogeneity. The problems with organoid size heterogeneity appear to come about due to the instability and diffusion limitation of Wnt3a which causes a concentration gradient within a conventional 2D extracellular hydrogel matrix.

The study found that a three-dimensional approach to creating organoid cultures in the dome mitigates common problems with a 2D approach in respect to morphological, functional, transcriptional, and translational heterogeneity which leads to false interpretations. The team hope that this study will provide invaluable insights into how to mitigate these issues.

Using Porcine Intestinal Organoids to Construct an Optimized, Near Physiological 2D Culture System

In another promising study, researchers have used porcine stem cells to explore how to construct an optimized 2D organoid culture.

Three-dimensional stem-cell derived intestinal stem cell derived organoids have a limitation. To rigorously test substances such as food components and bioactive compounds, easy access to the apical epithelium is not always possible. Challenges form due to heterogeneity in organoid size, problems of synchronous exposure, and variability of injected volumes. Cell debris can also accumulate. These can bind or hinder the ability of the lumen and injected substances to interact.

The study, published in a 2018 issue of Stem Cell Research, demonstrated a new robust method for generating stable confluent intestinal cell monolayers from single-cell suspensions of porcine organoids. Cell-seeding densities can be standardized using modified culture conditions, overcoming the inherent problems associated with other methods of creating organoid cultures.

Another limitation which can occur is long-term viability of organoid cultures. Indeed, previous methods of growing 3D porcine intestinal organoids demonstrated that they were limited to around ten passages. In this study, spheroids were formed within 3-5 days and matured within 7-10 days without restrictions such as the Hayflick limit. By using the method developed in the study, passage of 3D organoid cultures was found to be possible for several months.

In Conclusion

Organoids are very much a technology still under development, although the possibilities demonstrated by recent studies shows huge promise for the continued integration of the technology into future studies. Approaches such as this represent the cutting edge of scientific research today and future developments will no doubt provide new paradigms for combatting diseases which affect vast swathes of the human population.

Sources

De Souza, Natalie (2017) Organoid Culture Nature Methods Vol. 14 Issue 35 [Accessed Online 5th October 2020] https://www.nature.com/articles/nmeth.4122

Shin, q, et al. (2020) Spatiotemporal Gradient and Instability of Wnt Induce Heterogenous Growth and Differentiation of Human Intestinal Organoids iScience Vol. 23, Issue 88, 101372 [Accessed Online 5th October 2020] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101372

Van der Hee, B. (2018) Optimized procedures for generating an enhances, near physiological 2D culture system from porcine intestinal organoids Stem Cell Research Vol. 28 pp. 165-171 [Accessed Online 5th October 20202] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1873506118300576

Further Reading

Last Updated: Dec 18, 2020