In 2018, Arthur Ashkin was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work describing 'tools made of light'. This refers to optical tweezers, which are instruments that use a highly focused laser beam to ‘pin down’ or immobilize, using a physical force, a microscopic object.

“When I described catching living things with light people said, 'Don’t exaggerate Ashkin'.”

Microscopic objects may also be moved using this phenomenon. In this field, they are viewed as tweezers that operate in much the same way the conventional macroscopic variety. Bioscientists can use these tools to explore biological macromolecules on the micro-level.

This has allowed considerable advancements in knowledge of macromolecular structure and movement. It has also been implemented in conjunction with other techniques such as Raman spectroscopy, which enables identification of healthy or cancerous cells.

Exploiting Photons Using Lasers to Produce Tweezers

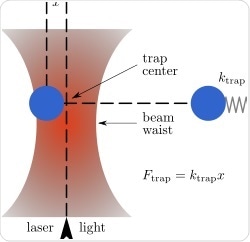

Optical tweezers are also known as optical traps. They exploit the phenomenon of light exerting force on matter. Dielectric particles, which are electrical insulators that can be polarized by an electric field, are attracted to and held in the vicinity of a highly focused laser beam, i.e. the trap.

The photons that comprise the light beam each carry momentum, and therefore collectively exert force. A resulting electric field gradient is also produced, which is strong enough to hold the dielectric particle in a position. These traps can be manipulated so that they do not interfere with the movement produced by single molecules.

These dielectric particles are typically beads made of polystyrene or silica, ∼1 μm in diameter. Biological macromolecules or beads become attracted to the electric field generated by the photons of light. They remain in this position, allowing observations to be made.

The force and movements that are involved in the interaction between the bead and the partnering molecule can be measured or manipulated by moving the trap. In theory, the same type of experiment can be performed with atomic force microscopes (AFMs) or microneedles, however, these probes show much less compliance and will not enable force generation by single molecules to be detected.

Applications of Optical Tweezers

Optical tweezers are used widely in physics, chemistry, and biology. They are especially useful in single molecule studies. The first documented application of optical traps in the 1970s was in the trapping of viruses and bacteria. This required careful manipulation of the wavelength to trap bacterial cells. Based on this work, researchers succeeded in trapping different cell types, such as green algae, amoebas, and other protozoa.

The pioneering research by Ashkin et al. demonstrated that a highly-focused laser beam generated using a microscope could attract particles towards it, and subsequently shift particle positioning due to their attraction to the laser focal point.

This field of biophysics has benefitted greatly from the use of optical tweezers. they can be used to sort healthy cells, identify cancerous cells, and measure nanoscale movements of trapped objects and the forces they exert. This has aided in elucidating how molecular motors, which generate movement in microscopic organisms and organelles, function.

Molecular motors feature widely in biology, in muscular contraction and the generation of ATP in the mitochondria, for example. Novel applications of optical tweezers have included measuring the mechanical an elastic property of key biological molecules such as DNA.

Ashkin’s work comprised one half of the 2018 Nobel Prize in physics, with the work of Gérard Mourou and Donna Strickland being jointly awarded for their development of ‘chirped pulse amplification’ (CPA). CPA describes a method for producing short, high-intensity laser pulses.

Before this work, the production of ultra-fast pulses had been stymied by the limited technology of the time. The generation of high intensities was impossible due to the damage caused to the amplifier. With the breakthrough of CPA, laser intensity could be approximately doubled.

The technique uniquely stretches a short light pulse fired from a laser, which reduced its peak power. The stretched pulse is then amplified before being compressed to its initial magnitude, resulting in a dramatically increased laser intensity. The resultant laser pulses are incredibly brief and very sharp, a property that is desirable in laser eye surgery to correct nearsightedness

Optical tweezers are a technical tool that utilizes the phenomenon of optical trapping. This enables the manipulation of small objects on the microscale level. Specifically, a tightly focused laser beam is, in effect, the optical trap. Any object in the vicinity of the focal point experiences an interplay of both attractive and repulsive forces that culminate to produce a pinning force.

The production of such an optical trap requires several conditions. These include a weak absorption at the wavelength at which trapping occurs, a refractive index which surpasses the refractive index of the surrounding medium, and partial transparency. The optical trap, due to its limitations, has been adapted using optical tweezers, which do not directly trap the object itself. Instead, they operate as a probe, handle, or marker.

Sources

- K. Schakenraad, A. S. Biebricher, M. Sebregts, B. ten Bensel, E. J. G. Peterman, G. J. L. Wuite, I. Heller, C. Storm, and P. van der Schoot, “Hyperstretching DNA,” Nat. Commun. 8, 2197 (2017).

- A. Ashkin, J. M. Dziedzic, J. E. Bjorkholm, and Steven Chu, “Observation of a single-beam gradient force optical trap for dielectric particles,” Opt. Lett. 11, 288 (1986).

- A. Ashkin, Karin Schütze, J. M. Dziedzic, U. Euteneuer, and M. Schliwa, “Force generation of organelle transport measured in vivo by an infrared laser trap,” Nature 348, 346 (1990).

- D. Strickland and G Mourou, “Compression of amplified chirped optical pulses,” Opt. Commun. 56, 219 (1985).

Further Reading

Last Updated: May 30, 2019