In a recent study published in the journal Scientific Reports, researchers explored how bathing in Japanese hot springs affects the gut microbiota of healthy individuals. Their results provide fascinating insights into the benefits of using therapeutic springs.

Study: Effects of bathing in different hot spring types on Japanese gut microbiota. Image Credit: PR Image Factory / Shutterstock

Study: Effects of bathing in different hot spring types on Japanese gut microbiota. Image Credit: PR Image Factory / Shutterstock

Background

Drinking or bathing in hot spring or mineral water, referred to as balneotherapy, is known to benefit several health conditions. Individuals with skin and musculoskeletal diseases may benefit from improved quality of life and sleep, while hot spring baths may also improve hypertension, stress, cardiovascular disease, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and gynecological, rheumatological, and dermatological symptoms. Balneotherapy is thought to improve outcomes in people with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis by influencing the skin and gut microbiota.

Japan’s Hot Spring Law defines ten different categories or ‘spa types’ of therapeutic hot springs based on the substances they contain and their respective concentrations. The differences between these distinct types in terms of therapeutic benefits have not been studied. Further, it is unknown how they may affect healthy individuals without pre-existing health conditions.

About the study

This study examined how bathing in different categories of hot springs affects the gut microbiome in a sample of healthy individuals. Participants were recruited if they were between 18 and 65 years old, living in the Kyushu area, had not taken a hot spring bath in the previous two weeks, and did not suffer from any chronic illness.

Participants were asked to choose a hot spring facility and soak in the same tub for at least 20 minutes daily for seven consecutive days. Outside of the daily baths, they continued to follow their everyday routines and regular mealtimes and were requested to avoid excessive drinking and overeating. People who were unable to follow these criteria were excluded from the analysis. Each participant collected their fecal samples before and after the experiment. These were analyzed to identify gut microbiota and find the most common genera.

Findings

A total of 127 participants, including 52 females, completed the study and had their fecal samples analyzed. The types of hot springs they visited were simple, chloride, bicarbonate, and sulfur. Springs were categorized as simple if they had a temperature of over 25°C and less than 1g/kg of dissolved substances; chloride if they contained more than 1g/kg of chlorine, sulfur if they contained 2 or more mg/kg of sulfur, and bicarbonate if it contained more than 1 g/kg of dissolved HCO3.

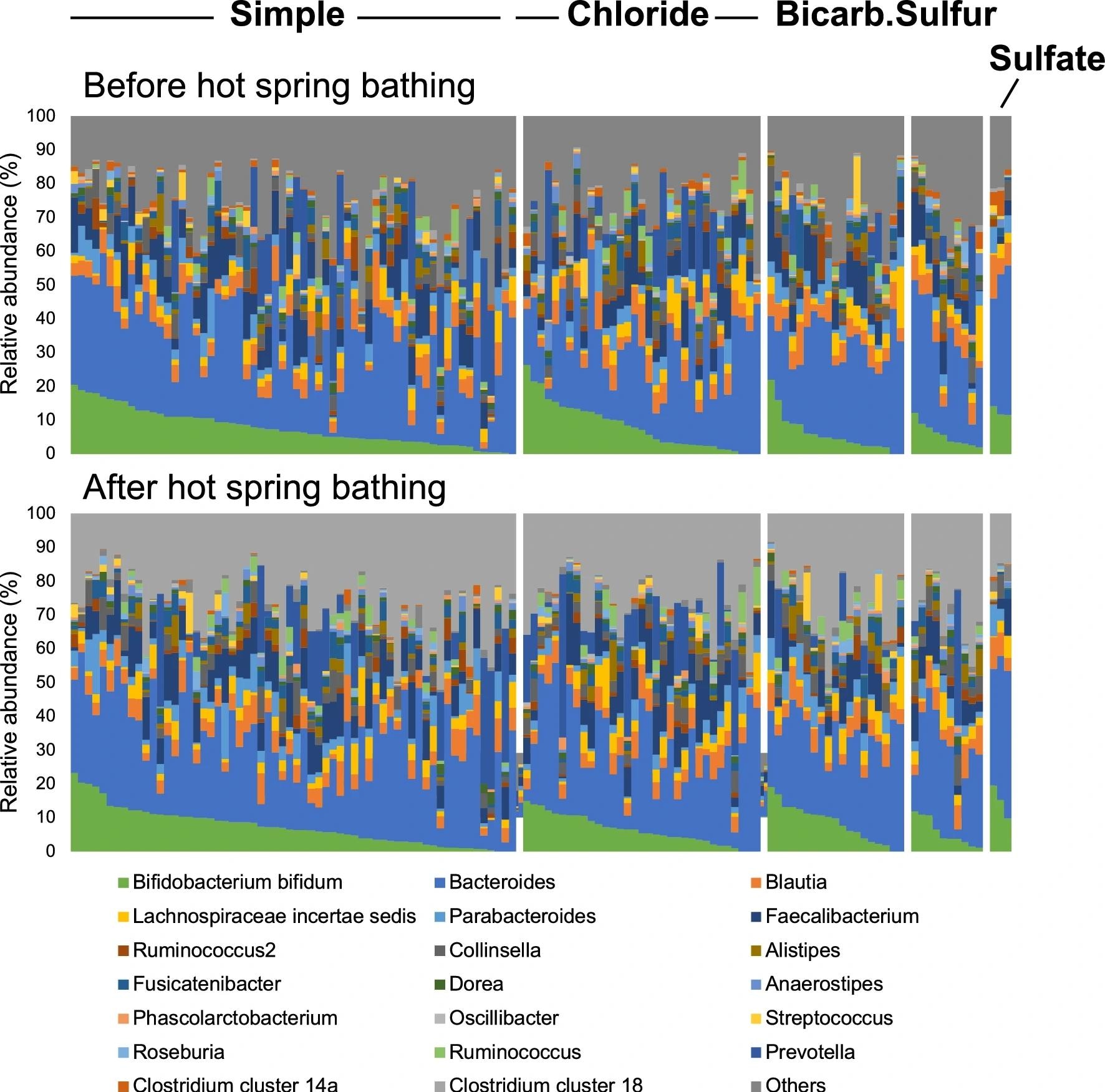

Comparisons of the relative abundance of gut microbiota before and after hot spring bathing. One of the stacked bars corresponds to one individual. Each hot spring bathing group is shown as a single mass, arranged starting with the individual with the highest Bifidobacterium bifidum value on the left. The upper row indicates before bathing, and the lower row indicates after bathing. The order of individuals is not identical in the upper and lower rows. ‘Bicarb.’ indicates ‘Bicarbonate’.

Comparisons of the relative abundance of gut microbiota before and after hot spring bathing. One of the stacked bars corresponds to one individual. Each hot spring bathing group is shown as a single mass, arranged starting with the individual with the highest Bifidobacterium bifidum value on the left. The upper row indicates before bathing, and the lower row indicates after bathing. The order of individuals is not identical in the upper and lower rows. ‘Bicarb.’ indicates ‘Bicarbonate’.

Seven bacteria showed significant increases after the bathing experiment, including Oscillibacter and Parabacteroides in the simple spring bathers, Ruminococcus, Oscillibacter, and Bifidobacterium bifidum in the bicarbonate spring bathers, and Alistipes and another species of Ruminococcus among the sulfur spring bathers. Of these, Oscillibacter was the only bacterium found in more than one group. There were no significant changes before and after the bathing intervention for individuals using the chloride springs.

Of these bacteria, B. bifidum showed the most significant change, with individuals exhibiting a 2.8% increase after they bathed in bicarbonate springs. Using simple springs was associated with a 0.7% increase in Parabacteroides. Oscillibacter, which increased in two groups, rose by 0.31% in those using bicarbonate springs and 0.14% in those using simple springs. Sulfur springs increased Alistipes concentrations by 1.5% and Ruminococcus2 by 0.87%.

Conclusions

The findings from this study, which is the first to look at the effects of hot spring bathing on gut microbiota, indicate that the unique mineral properties of different hot spring types can distinctly modify the gut microbiome by increasing the concentrations of some bacteria. Further research can draw on these baseline findings to establish how these unique chemical profiles can be used to target specific microbe responses.

The increase in B. bifidum concentrations in users of bicarbonate springs is of particular interest because it is known to increase glucose tolerance, alleviate constipation, strengthen gut immunity, and be protective against enteropathogenic infections. Other bacteria have mixed effects – Parabacteroides may worsen the symptoms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) but are also associated with longevity.

The authors note that a significant limitation of this study is the lack of a control group and the use of a before-after comparison. Future studies can use a ‘sauna control’ or include a ‘no bathing’ group to address this issue while also drawing on people from other communities and populations to ensure generalizability. Further work in this field can identify improved therapies for individuals with different health issues, ensuring the increase in healthy bacteria while also limiting increases in less beneficial genera.