Infections within the mediastinum (known under an umbrella term mediastinitis) are very serious conditions, linked to high morbidity and mortality rates, and can be a result of direct extension from a certain disease process, hematogenous spread, or by a traumatic introduction to the mediastinal region.

Image Credits: Tomatheart / Shutterstock.com

Image Credits: Tomatheart / Shutterstock.com

Acute mediastinitis can be divided into the postoperative deep sternal infections with subsequent infection, mediastinitis due to perforation of the esophagus and aerodigestive tract, and descending necrotizing mediastinitis. The most common cause of mediastinitis in clinical practice is the direct invasion of the mediastinum following surgical interventions.

Any delay in establishing the correct diagnosis significantly influences morbidity and mortality rates, as well as overall clinical outcomes. Nonetheless, mediastinitis is usually recognized on time due to high awareness in susceptible populations with a plethora of risk factors (such as obesity, smoking, diabetes, obstructive lung disease, peripheral arterial disease, prior heart or thoracic surgeries).

Symptoms and clinical presentation of mediastinitis

The manifestations of mediastinitis range from the subacute, indolent and stable condition to the fulminant and rapidly developing critical disorder that requires prompt interventions to prevent complications and death.

Patients classically present with tachycardia (increased heart rate), chest pain, fever, sternal instability (in the case of sternal wound infection), and purulent (pus-filled) drainage from the sternal region. Affected individuals that have non-operative mediastinitis occasionally present with a sepsis-like syndrome, or even frank sepsis.

Atypical presentation of mediastinitis has also been described repeatedly in the medical literature. Patients may present only with postoperative fever, may have asymptomatic postoperative bacteremia, or superficial wound infection may be the only visible sign. A normal, uneventful postoperative course excludes the presence of the condition.

In any case, when evaluating patients presenting with symptoms of mediastinitis, certain differential diagnoses should be suspected. These include aortic dissection, acute coronary syndrome, acute pericarditis, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, pneumothorax, and deep neck infection.

Clinical criteria for diagnosing mediastinitis

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have issued guidelines defining mediastinitis as a condition that requires at least one of the following criteria: microorganisms cultured from mediastinal fluid or tissue, evidence of mediastinitis on histopathological and/or gross examination, as well as symptoms such as fever, chest pain or sternal instability.

In addition, there will be evidence of purulent drainage from the mediastinal region or mediastinal widening observed on imaging. Post-sternotomy mediastinitis is further defined by more comprehensive criteria that help distinguish between superficial and deep infections.

The diagnosis of mediastinitis is confirmed when purulent discharge with necrotizing infection is found intraoperatively. Furthermore, patients who present with typical symptoms within 2 weeks of either cardiovascular or thoracic surgery should be considered to have mediastinitis – therefore immediate treatment is warranted.

Ancillary laboratory and imaging studies

Laboratory abnormalities are often seen in patients with mediastinitis, especially if it is associated with sepsis. Leukocytosis (an increased number of white blood cells), acidosis (increased blood acidity) and elevated lactate levels are the most common findings. Bacteremia (the presence of bacteria in the blood) can be observed in more than 50% of cases.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) – with the addition of oral contrast when the presence of esophageal lesion is suspected – represents the diagnostic approach of choice. Both the underlying cause and the extent of infection may be appraised by using this method. Other imaging techniques may also be used, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and labeled white blood cell (WBC) scan.

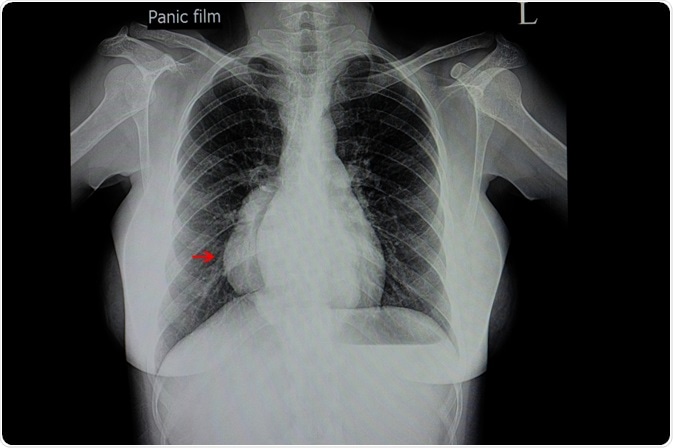

Plain chest radiography is not useful but may be helpful when alternative causes of fever are suggested (such as atelectasis or pneumonia). Likewise, pericardial or pleural effusion, pneumomediastinum, and empyema that may be a consequence of mediastinitis can also be revealed by X-ray imaging.

Sources

Athanassiadi , K.A. (2009) Infections of the mediastinum. Thorac Surg Clin. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2008.09.012.

Pierce, T. B. et al. (2000). Acute mediastinitis. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center), 13(1), 31–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2000.11927639

Abu-Omar, Y. et al. (2017). European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery expert consensus statement on the prevention and management of mediastinitis. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezw326

Prado-Calleros, H.M. et al. (2016). Descending necrotizing mediastinitis: Systematic review on its treatment in the last 6 years, 75 years after its description. Head Neck. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.24183

Kluge, J. (2016). Acute and Chronic Mediastinitis. Surgeon. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00104-016-0172-7

Pastene, B. et al. (2020). Mediastinitis in the intensive care unit patient: a narrative review. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2019.07.005

Rees CJ, Cantor RM, Pollack Jr. CV, Riese VG. Mediastintis. In: Pollack Jr. CV (eds) Differential Diagnosis of Cardiopulmonary Disease. Springer, Cham, Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019

Further Reading

Last Updated: Apr 7, 2020