Mediastinitis is an inflammation of the tissues that are situated in the mid-chest cavity or mediastinum.

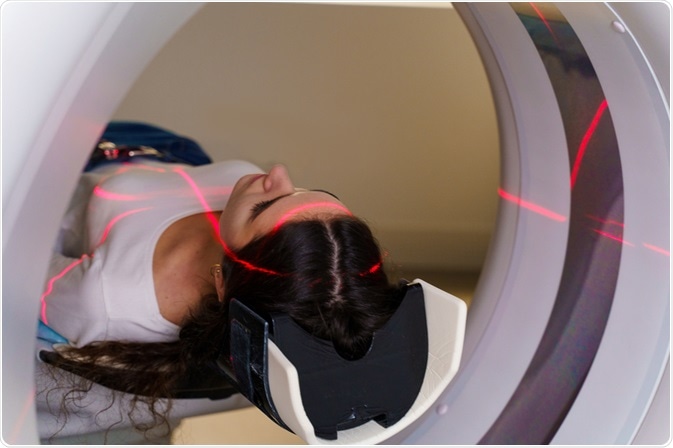

Image Credit: Rabizo Anatolii/Shutterstock.com

The pathophysiology of mediastinitis is rather complex, but the common pathway for post-operative forms of the disease (which are most common) seems to be intraoperative contamination of the wound, related more to patient factors than the surgical technique used.

Mediastinitis can be acute or chronic, and either infectious or non-infectious. The majority of acute mediastinitis cases are secondary to open chest surgery (deep sternal wound infection) and esophageal perforation. The third most common type is descending necrotizing mediastinitis.

Less frequent causes of mediastinitis include bronchial or tracheal perforation or direct infectious spread from adjacent tissues.

Tuberculosis, histoplasmosis (and other fungal infections) and malignant diseases give rise to chronic or subacute mediastinitis. Autoimmune disease or lymphatic obstructions are also very rare causes of this clinical entity.

Deep sternal wound infection

Deep sternal wound infection is a process in which the mediastinum becomes infected due to a deep wound infection after sternotomy, which is used primarily in heart surgery. Recent studies have shown that between 0.5 and 2.2% of patients who undergo cardiac surgery develop mediastinitis, with a resultant mortality rate of almost 14%.

Risk factors for developing deep sternal wound infection can be either patient-related or procedure-related. The most common patient-related risk factors are older age, obesity, diabetes, smoking, obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, elevated levels of creatinine, colonization with Staphylococcus aureus and heart failure.

On the other hand, procedure-related risk factors for developing deep sternal wound infection are prolonged operative time, special types of operations (such as the use of aortic clamping, on-pump perfusion, and specific artery grafts). Tracheostomy is also described as a risk factor for deep sternal wound infection.

Perforation of the esophagus

Since the esophagus is densely colonized by commensal (but also healthcare-associated) microorganisms, cervical and thoracic esophageal perforations give rise to mediastinitis coupled with very high mortality rates.

Iatrogenic perforation during endoscopic procedures is considered to be responsible for up to 60% of all perforations of the esophagus. Immediately following the perforation retained gastric contents, saliva, acid, and bile enter the mediastinum and result in the inflammation.

Spontaneous perforation (which includes Boerhaave syndrome) is responsible for 15% of all perforations, generally located at the posterior aspect of the distal part of the esophagus.

Malignant and traumatic perforations also represent a significant percentage of cases (up to 17%). Esophageal perforation may also take place due to surgical anastomosis failure.

Descending necrotizing mediastinitis

Descending necrotizing mediastinitis is a rather serious process (infectious) that emerges from the nose, ears or throat and then spreads inferiorly via connective-tissue planes into the mediastinum. This clinical entity is characterized by a severe infection of the oropharynx with coincident radiological findings that indicate mediastinitis.

In a majority of instances, descending necrotizing mediastinitis is a result of odontogenic or pharyngeal infections (80%), but also cervical infections (15%). Unknown sources account for the remaining percentage.

The main risk factors include immune deficiency, diabetes, oral use of corticosteroids, peripheral artery occlusive disease, respiratory insufficiency, sepsis, and heart failure. The mortality of this condition is high, with reports in the literature ranging between 15% and 30%.

Rare forms of mediastinitis

Sclerosing mediastinitis (also known as chronic fibrosing mediastinitis) represents a more insidious type of mediastinitis that most often arises as a complication of granulomatous infections – frequently due to Histoplasma capsulatum or sometimes Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

In a majority of patients, the infection with Histoplasma capsulatum is subclinical and starts as an asymptomatic infection of the lungs that disseminates to the lymphatic nodes in the mediastinum. The affected nodes then enlarge and merge to a caseous mass (granuloma) or may instantly lead to sclerosis.

Finally, silicosis, sarcoidosis, and paraffin infections (late severe complications of tuberculosis treatment methods for cavitary forms of the disease) can also mimic chronic mediastinitis. Certain malignancies should also be considered in the diagnostic appraisal of every patient with suspected mediastinitis.

Sources

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1312210/

- https://academic.oup.com/ejcts/article/51/1/10/2670570

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/hed.24183

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00104-016-0172-7

- https://www.clinicalmicrobiologyandinfection.com/article/S1198-743X(19)30394-5/fulltext

- Rees CJ, Cantor RM, Pollack Jr. CV, Riese VG. Mediastintis. In: Pollack Jr. CV (eds) Differential Diagnosis of Cardiopulmonary Disease. Springer, Cham, Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019

Further Reading

Last Updated: Apr 10, 2020