The three-dimensional structure of a protein is highly conserved compared to the primary sequence. Thus, comparing the overall structure and shape of a protein, rather than its sequence, is considered to be a more eloquent way of assigning a function to a protein.

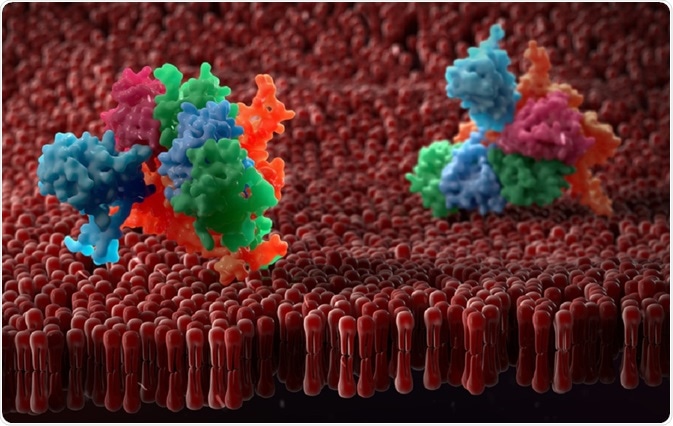

urfin | Shutterstock

urfin | Shutterstock

Predicting the function of a protein

The function of a protein is usually determined by the ligands that it binds to. The 3D structure of the binding groove or pocket can be compared to other proteins and similar residues used to make educated guesses about the function of the protein. This is called structure-based prediction.

There are several approaches to structure-based prediction, and these fall into two classes: geometry-based approaches and energetics-based approaches.

- Geometry based approaches identify pockets within the protein and examine them for any key residues that could be involved in ligand binding.

- Energetics-based approaches use biophysical equations to quantify the binding energies of residues speculated to perform a binding function.

Geometry-based approaches

In geometry-based approaches, computational programs are used to identify sites of biochemical activities in or on the protein. Examples of these programmes include Surfnet, CASTp, Ligsite, and PocketFinder. These programmes survey the proteins or active site pocket to determine the identity of the amino acids that form them.

Surfnet uses the amino acid coordinate data stored in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) to generate a series of protein surfaces such as pockets, grooves, and spaces (called voids) between proteins. The output of the program is a series of depictions of these surfaces that show the atomic density across the surveyed region in a grid-like format.

Residues present in the regions of the highest atomic density are important in protein-binding function. Contrastingly, programmes such as CASTp locate voids in protein structures. CASTp also uses data from the PDB and another annotated protein database, called SwissProt to characterise the amino acids that form the void. Finally, CASTp searches a database called OMIM (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man), which catalogues human genes and genetic disorders.

Similarly, the programme Ligsite generates a series of ligand-receptor complexes to detect the presence of pockets on proteins. PocketFinder searches for envelops or folds within, rather than on the surface of the protein

Energetics-based methodologies

When a protein binds a ligand, the resultant complex is stabilised due to the dissociation free energy of the complex at a given ligand concentration. The stability of the complex alters the energetic properties of the protein, such as an increased thermodynamic stability.

Energetics-based approaches exploit changes in the energetic properties of a protein that result from ligand binding to characterize the identity of its partners and infer function. Ligand binding site prediction tools, such as Q-Site Finder uses an energetics-based approach to identify ligand binding pockets.

In this computational programme, the protein surface is covered in methyl (-CH3) probes to calculate non-covalent forces called Van Der Waals interaction energies between the protein and the probe. The regions of the protein that display the most favorable interaction energy are noted by their coordinates which are subsequently used to locate them in the structure.

Individual probe coordinates are them grouped according to their relative positions to one another, and the total energy of each cluster is calculated. Each cluster is then ranked, and the cluster that possesses the most favorable energy is identified as the binding site.

Disadvantages of choosing one method

Reliance on structure-based methods alone increases the probability of misannotation. The prevailing methodology for protein function prediction, therefore, relies on the use of parallel methods. For example, sequence-based methods alongside structure and genomics-based methodologies.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 23, 2023