Researchers in China and Australia have reported the discovery of novel bat coronaviruses that further reveal the diversity and complex evolutionary history of these viruses.

In early 2020, the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was identified as the causative agent of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak that first began in Wuhan, China, in late December 2019.

A combination of genome sequencing and sampling studies then identified a number of SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses in wildlife species that together pointed to underestimation of the phylogenetic and genomic diversity of coronaviruses.

Now, Weifeng Shi from Shandong First Medical University & Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences in Taian, China and colleagues have conducted a meta-transcriptomic analysis of samples collected from 23 bat species in Yunnan province in China during 2019 and 2020.

“Our study highlights both the remarkable diversity of bat viruses at the local scale and that relatives of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV circulate in wildlife species in a broad geographic region of Southeast Asia and southern China,” says the team.

“These data will help guide surveillance efforts to determine the origins of SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogenic coronaviruses.”

A pre-print version of the research paper is available on the bioRxiv* server, while the article undergoes peer review.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Bats are well-known hosts of coronaviruses

Bats are well-established hosts to a broad range of viruses that are known to cause severe disease in humans, including the Hendra virus, Ebola virus and, most notably, coronaviruses.

Four of the seven known human coronaviruses have zoonotic origins. These include the SARS-CoV virus responsible for the 2002 to 2004 SARS outbreak and the Middle East respiratory coronavirus (MERS-CoV) responsible for numerous outbreaks of severe respiratory illness across the Middle East since 2012.

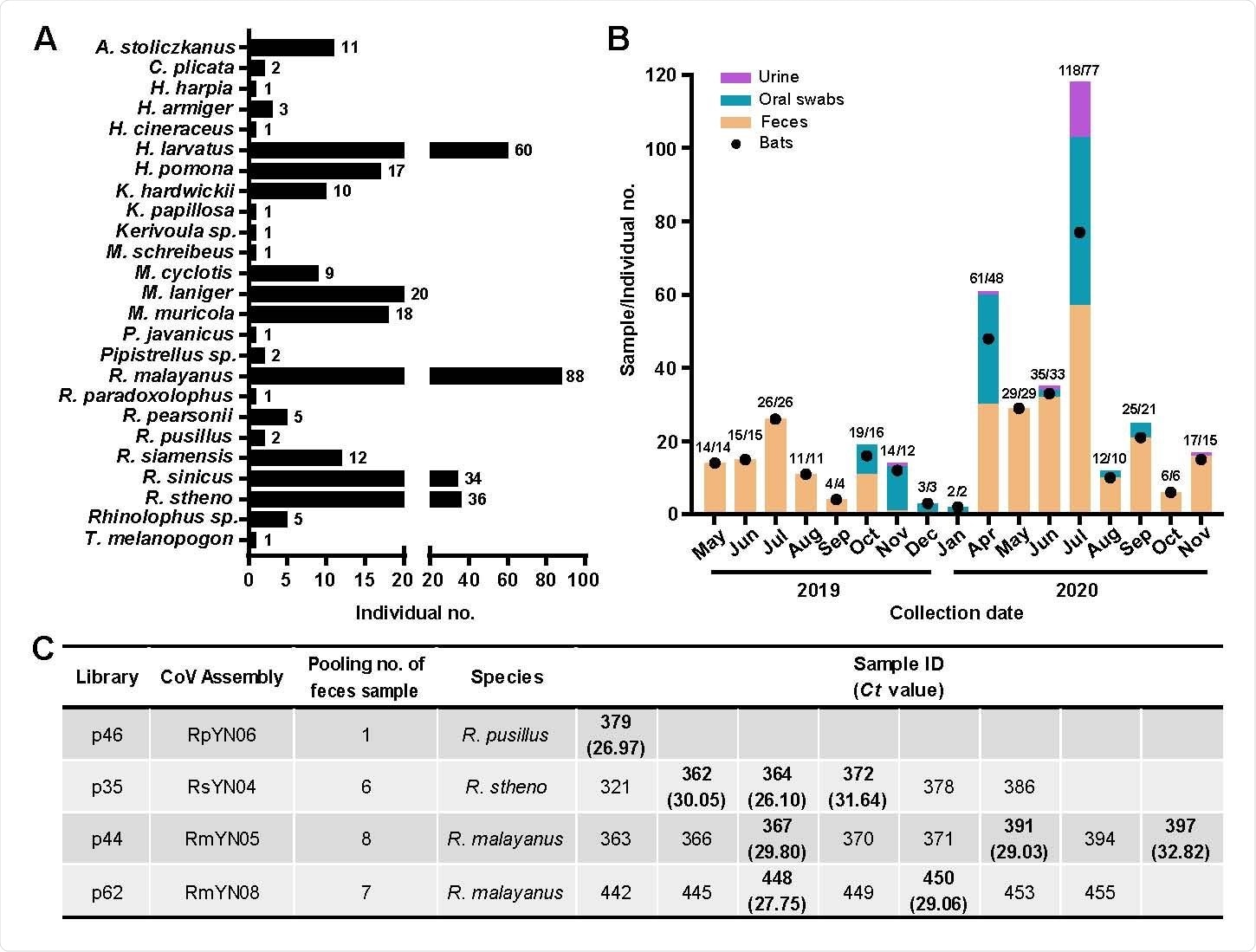

Sampling information and detection of SARS-CoV-2-like viruses in individual bat fecal samples. (A) Sample numbers of different bat species captured live in Yunnan province from May 2019 to November 2020. (B) Numbers of samples collected from different time points (orange column - feces; green - oral swab; light purple - urine). The numbers of individual bats are shown with black dots and relate to the y-axis. The associated numbers are in the form sample numbers/number of individual bats. (C) Identification of SARS-CoV-2-like virus positive samples using qPCR.

Although bats are the most likely hosts of these coronaviruses, their emergence in humans has also sometimes involved “intermediate” hosts such as the palm civet (in the case of SARS-CoV) and dromedary camels (MERS-CoV).

In early 2020, the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus was identified as the causative agent of a pneumonia outbreak in Wuhan, China, that quickly turned into a global pandemic.

A combination of retrospective genome sequencing and sampling studies identified a number of SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses in wildlife species.

These included the RaTG13 virus found in the Rhinolophus affinis bat, which is the closest known relative of SARS-CoV-2 across the viral genome as a whole.

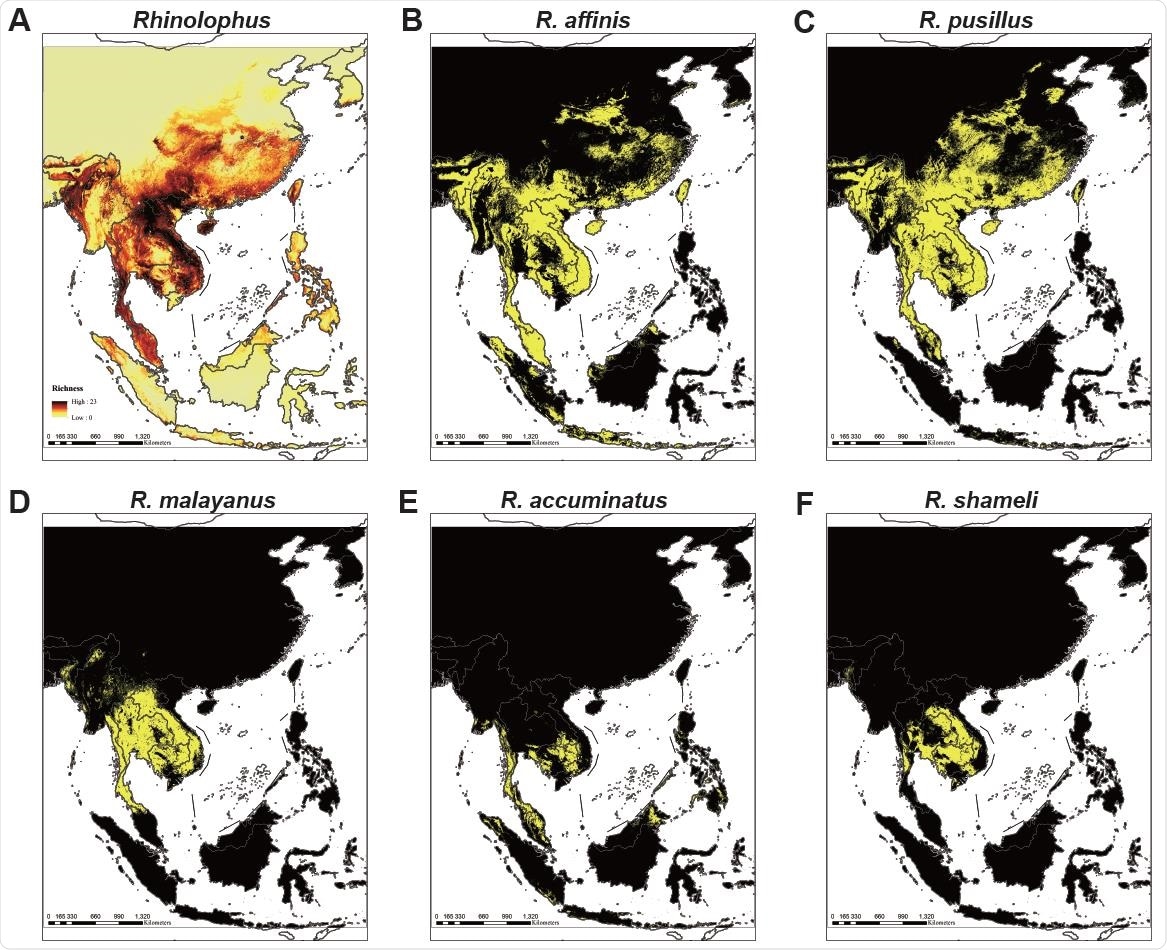

Ecological modeling the geographical distribution of 49 Rhinolophid bat species. (A) Models of 49 Rhinolophus bat species that predict diversity in five regions covering mainland Southeast Asia, Philippines, Java-Sumatra, Borneo and Sulawesi-Moluccas. The map color represents species richness, with up to 23 species projected to co-exist. (B-F) Location distribution of (B) the RaTG13 host species R. affinis, (C) the RpYN06 host species R. pusillus, (D) the RmYN02 host species R. malayanus, (E) the RacCS203 host species R. accuminatus, and (F) the STT182 and STT200 host species R. shameli. The yellow region represents the predicted range of each species.

SARS-CoV-2-related viruses have also been identified in various other Rhinolophid bats, including R. shameli bats sampled in Cambodia, R. cornutus bats sampled in Japan, and R. acuminatus bats sampled in Thailand.

“Collectively, these studies indicate that bats across a broad swathe of Asia harbor coronaviruses that are closely related to SARS-CoV-2 and that the phylogenetic and genomic diversity of these viruses has likely been underestimated” says Shi and the team.

What did the researchers do?

To further investigate the diversity, ecology, and evolution of bat viruses, Shi and colleagues conducted a meta-transcriptomic study of 411 samples collected from 23 bat species in a small (~1100 hectare) region within Yunnan province China, between May 2019 and November 2020.

The team identified coronavirus contigs (sets of overlapping DNA sequences) in 40 of 100 sequencing libraries, including seven libraries with contigs that could be mapped to SARS-CoV-2.

The team obtained novel coronavirus genomes

From these data, the researchers assembled 24 full-length novel coronavirus genomes, including four genomes related to SARS-CoV-2 and three related to SARS-CoV.

Notably, one of these novel bat coronaviruses – RpYN06 – exhibited 94.5% sequence identity to SARS-CoV-2 across the whole genome. Furthermore, in some individual genes (ORF1ab, ORF7a, ORF8, N, and ORF10), RpYN06 was the closest relative of SARS-CoV-2 identified to date.

However, at the genomic scale, low sequence identity in the spike gene made RpYN06 the second closest relative of SARS-CoV-2, next to RaTG13. The spike protein is the main structure SARS-CoV-2 uses to bind to and infect host cells.

Differences in the overall sequence of the spike gene

The researchers say that although several SARS-CoV-2-like viruses have previously been identified in different wildlife species, none are highly similar (>95% ) in the overall sequence identity of the spike gene.

Indeed, while the other three SARS-CoV-2-related viruses identified here were almost identical in sequence, the spike protein sequences formed an independent lineage that was separated from known sarbecoviruses by a relatively long branch. Sarbecovirus is a viral subgenus or the coronaviruses that SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV belong to.

“Collectively, these results highlight the extremely high, and likely underestimated, genetic diversity of the sarbecovirus spike proteins, which likely reflects their adaptive flexibility,” writes Shi and colleagues.

The researchers say studies have previously shown that host switching of coronaviruses among bats is a frequent occurrence.

“That individual bat species can harbor multiple viruses increases the difficulty in resolving the origins of SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogenic coronaviruses,” they add.

What else did the study find?

Ecological modeling predicted the co-existence of up to 23 species of Rhinolophus bats species across much of Southeast Asia and southern China, with the largest hotspots for high bat diversity extending from South Lao and Vietnam into southern China.

The researchers say that in addition to Rhinolophids, this broad geographic region in Asia is also rich in many other bat families and other wildlife species that have been shown to be susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 in vitro.

“It is, therefore, essential that further surveillance efforts should cover a broader range of wild animals in this region to help track ongoing spillovers of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV and other pathogenic viruses from animals to humans,” they conclude.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources