Research has documented evidence on the effect of sex differences in various biological functions such as brain function or dysfunction, sex-specific response to stress, neurogenesis, cognitive functions and other biological functions during the pre-natal and post-natal phases of a mammal.

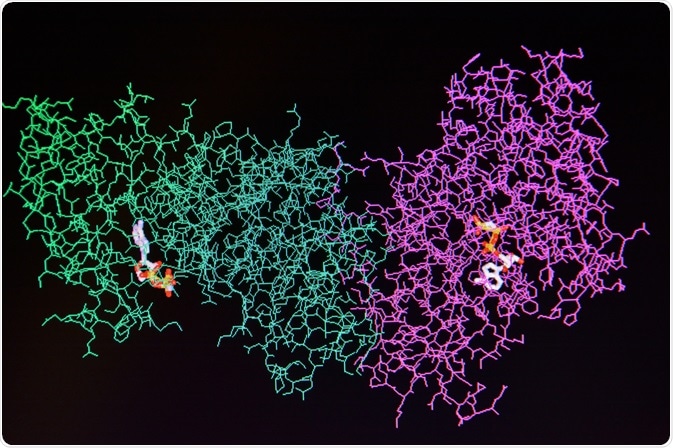

Image Credits: Sergei Drozd / Shutterstock.com

Image Credits: Sergei Drozd / Shutterstock.com

Effect of sex difference on synaptic proteins

Advancing research in the area of pharmacology and neuroimaging technology has helped scientists differentiate males and females not only from the anatomical point of view but also at the synaptic level. While some synaptic mechanisms are the same between different sexes, some mechanisms have opposite effects depending on the sex.

A study by Sarkar et al. studied the effects of isolation stress and antidepressants on the expression of synaptic proteins such as glutamate receptor 1, synapsin-1, and postsynaptic density protein 95 in male and female rats. A decrease in the level of all three synaptic proteins was observed in male rats after 8 weeks of isolation stress.

However, single-dose parenteral administration of the antidepressant reversed these changes. On the other hand, female rats exhibited decreased levels of all three synaptic proteins after 11 weeks of isolation stress that could not be reversed by parenteral administration of the antidepressant. Thus, the study implies the possibility of sex differences in eliciting different biological or therapeutic responses.

Relationship between gender and protein expression in neurodegenerative and cardiac diseases

Hill et al. studied the role of neurotrophins in schizophrenia. Measurement by Western Blot analysis showed enhanced levels of protein expression of neurotrophins in males compared to females.

A study of gender-specific heart protein expression of approximately 10 proteins by Diedrich M et al. in male and female mice, using mass spectrometry and two-dimensional electrophoresis, also demonstrated sex-dependent protein expression. While Diedrich M et al. observed that most sex-specific protein expression was also dependent on age, expression of proteins such as peroxiredoxin 2, involved in redox regulation, was higher in females than in males.

In addition, the study revealed the male mice heart to be susceptible to advanced oxidation of apolipoproteins producing higher levels of reactive oxygen species, a contributing factor in cardiovascular diseases such as coronary heart disease and atherosclerosis.

Role of sex-specific protein expression in metabolic disorders

Consumption of a high-fat diet during pregnancy has been linked to obesity, high triglyceride levels and even kidney malfunction in offspring. Nguyen et al. have attempted to demonstrate a link between maternal overnutrition and diminished ability in the offspring to respond to stress such as autophagy, inflammation, or antioxidation along with dysregulation of renal lipid metabolism.

Their study showed male offspring to have higher deposition of renal lipids due to reduced expression of the protein Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) and downregulation of signaling proteins such as 5´AMP activated protein kinase, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor- γ (PPARγ), and forkhead box 03a (FOX03a).

Downregulation of SIRT1, FOX03a, and PPARγ in male offspring could contribute to the development of chronic kidney diseases in adulthood compared to female offspring where there is no change in expression of these components.

Sex-specific protein expression in developmental disorders

Human protein-coding genes Foxp1 and Foxp2 are necessary for proper neurological development in humans. Genetic variations in Foxp1 and Foxp2 are responsible for intellectual disabilities, autism, as well as speech and language disabilities.

A study specifically on the brain of neonatal Foxp1 knock out (KO) mice demonstrated highly diminished ultrasonic vocalizations calls necessary for mating and other social interactions. Quantification of Foxp1 and Foxp2 proteins in the striatum and cortex of a specific inbred strain of wild type (WT) mice demonstrated male mice expressing 25% lesser Foxp2 than female WT mice.

In addition, the study researchers also observed that the sex-specific hormone, androgen, had an effect on Foxp1 expression as Foxp1 and the androgen receptor are co-expressed in the mice cortex and striatum. Mice with brain-specific androgen knocked out showed diminished Foxp1 expression in the striatum suggesting sex-specific susceptibility to developmental disorders.

Sex-biased protein expression in therapy

Many studies have pointed out that mRNA is expressed differently in males and females. Guo L et al. sequenced and studied approximately 30 deregulated miRNAs profiles from the Cancer Genome Atlas database by creating four groups, i.e., lung adenocarcinoma in males (LUAD-male), lung adenocarcinoma in females (LUAD-female), uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma in females (UCEC-female), and prostate adenocarcinoma in males (PRAD-male).

While consistent deregulated miRNA expression was observed in the LUAD groups, some miRNAs such as miR-1306, miR-3647, and miR-328 were differently expressed in male and female groups.

For instance, miR-328 is an indicator of increased mortality risk in acute myocardial infraction and the tumor stage. Difference in expression of miR-328 in male and female specimens can provide insights into the occurrence and progression of various diseases.

Similarly, Colen RR et al. used data from the Cancer Genome Atlas and Cancer Imaging archives to carry out a retrospective study on the molecular profiles of male and female specimens in sex-specific cell death in glioblastoma. Magnetic resonance imaging volumes of tumor necrosis revealed higher tumor necrosis volumes in males than in females.

During survival analyses using tumor necrosis volume and histopathological data, female subjects with lower necrosis volumes showed higher chances of survival. The results from the study suggest the need to have targeted sex-specific gene therapy for improved treatment outcomes.

Future direction

It would be important for the science community to delve further into the effect of sex differences on protein or gene expression to facilitate successful therapeutic intervention especially in life-threatening disorders/diseases.

Sources

Hyer MM et al. (2018), Sex Differences in Synaptic Plasticity: Hormones and Beyond, Front Mol Neuroscience. Available at doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00266

Sarkar A and Kabbaj M. (2016), Sex Differences in Effects of Ketamine on Behavior, Spine Density, and Synaptic Proteins in Socially Isolated Rats, Biological Psychiatry, 80(6), 448-456. Available at doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.12.025

Hill RA and Van den Buuse M. (2011), Sex-dependent and region-specific changes in TrkB signaling in BDNF heterozygous mice, Brain Research, 1384, p51-60. Available at doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2011.01.060

Diedrich M et al. (2007), Heart protein expression related to age and sex in mice and humans, International Journal of Molecular Medicine, 865-874. Available at doi: https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.20.6.865

Nguyen LT et al. (2017), SIRT1 reduction is associated with sex-specific dysregulation of renal lipid metabolism and stress responses in offspring by maternal high-fat diet, Scientific Reports 7, 8982. Available at doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08694-4

Frohlich et al. (2017), Foxp1 expression is essential for sex-specific murine neonatal ultrasonic vocalization, Human Molecular Genetics, 26(8), 1511-1521. Available at doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddx055

Guo L et al. (2017), miRNA and mRNA expression analysis reveals potential sex-biased miRNA expression, Scientific Reports 7, 39812. Available at doi: DOI: 10.1038/srep39812

Colen RR et al. (2014), Glioblastoma: Imaging Genomic Mapping Reveals Sex-specific Oncogenic Associations of Cell Death, Radiology, 275(1). Available at doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.14141800

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jun 19, 2020