Since the start of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, many have wondered if the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus responsible for COVID-19, can survive and spreads through contaminated surfaces of foods packaged by cold-chain processes.

Study: Low Risk Of SARS-Cov-2 Transmission Via Fomite, Even In Cold-Chain. Image Credit: SeventyFour / Shutterstock.com

Study: Low Risk Of SARS-Cov-2 Transmission Via Fomite, Even In Cold-Chain. Image Credit: SeventyFour / Shutterstock.com

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Background

Fomites typically become contaminated when an infected person sheds the virus onto their hands, which are then used to touch another surface. Sneezing, coughing, or simply speaking can shed SARS-CoV-2 through respiratory droplets or aerosols onto surfaces as well.

Recently, a paper reported that SARS-CoV-2 had been found in infectious form on an imported package of frozen cod in China. While prominent health organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have both declared the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission via contaminated objects (fomites) to be very low, public doubts linger.

Previous laboratory studies have suggested that SARS-CoV-2 can remain infective for days or weeks on many surfaces. Thus, these studies suggest that the low temperatures and reduced humidity typical of a cold-chain environment can allow the virus to remain stable for months.

When this is coupled with the detection of viral genetic material on widely touched surfaces, as in playgrounds, houses where one member is an asymptomatic infected individual, or in healthcare settings where surfaces are contaminated by the patients or other infected individuals, there is obviously a need to decipher the link between detectable viral ribonucleic acid (RNA) and infectious virus.

Notably, there have been only four reports of finding live virus in all the studies covering this aspect so far. Particularly in a cold-chain setting, there has not been any proof thus far that this is a route of transmission.

The highest risks of fomite-mediated transmission have been in childcare centers, hospitals, and food production facilities, aside from the infamous outbreak onboard the Diamond Princess.

Nonetheless, China has put in place elaborate tests for all imports of cold-chain products and their packaging, as well as treatment of these goods by wet wiping and disinfection. The current study uses a quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA) framework to evaluate the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission via fomites in cold-chain food packaging plants.

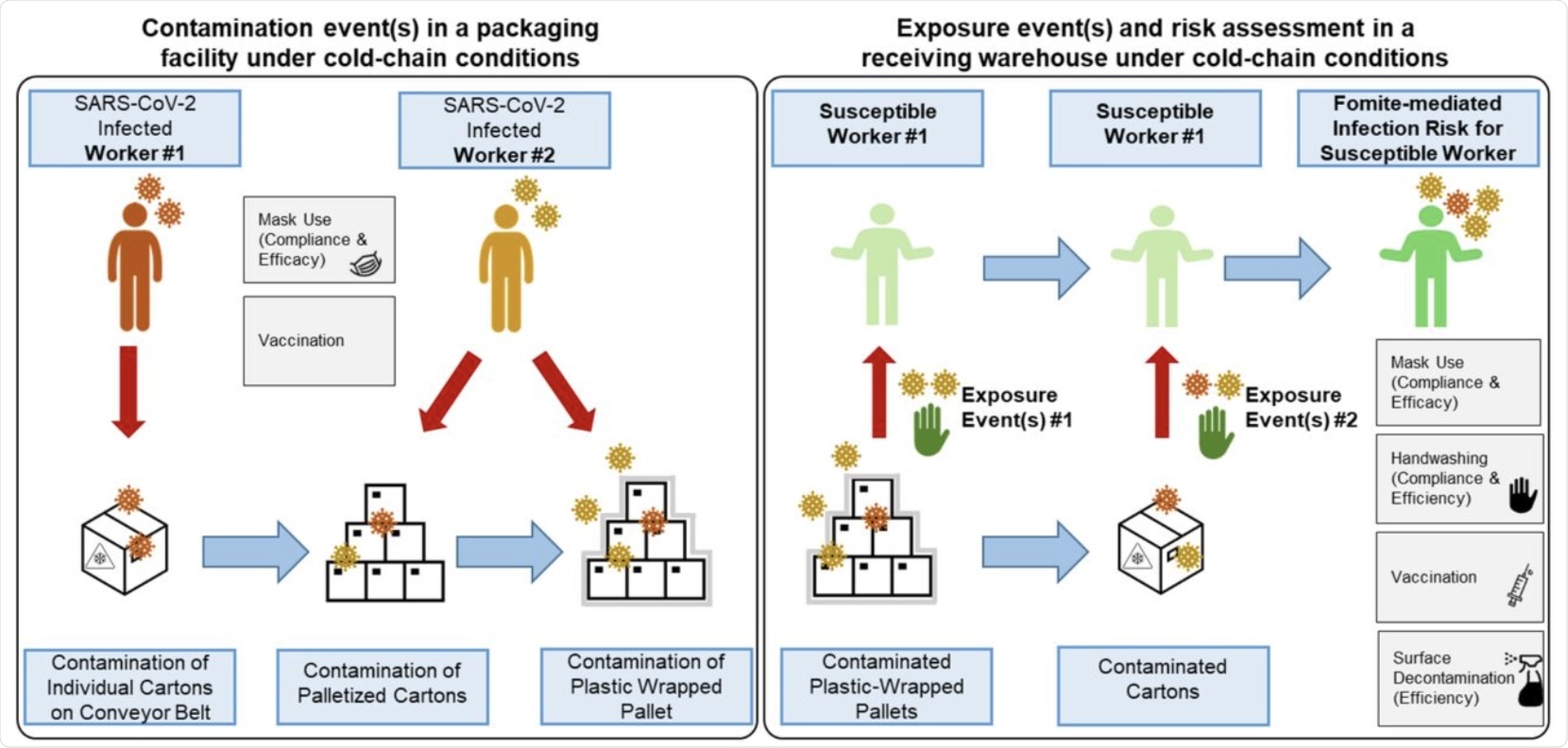

A conceptual framework for fomite-mediated SARS-CoV-2 transmission involving exposure of a susceptible worker to individual plastic cartons, palletized cartons, and plastic wrap in a receiving warehouse under cold-chain conditions. This schematic depicts a representative frozen food packaging facility, initiating with two infected workers (left panel). Up to 10 contamination events per infected worker (0 to 10 coughs) can occur at three stages in the packaging pipeline: 1) contamination of the top-face of individual plastic cartons (144-216 individual cartons processed per hour) via respiratory droplet and aerosol fallout from the first infected worker while cartons are transported along a conveyor belt (orange in schematic); 2) contamination of cartons via respiratory particle spray (droplets and aerosols) as cartons are placed (manually or via automation) on a pallet by the second infected worker (yellow in schematic); and 3) contamination of the plastic-wrapped palletized cartons by respiratory particle spray (droplet and aerosol) from the second infected worker (yellow in schematic). Four pallets, each containing approximately 36-54 individual plastic cartons, are processed per hour. Because of current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP), the model did not account for indirect transfer of virus from the infected workers’ hands to the plastic fomites along the packaging pipeline. Under cold-chain conditions assuming no viral decay, plastic wrapped pallets were transported to a receiving warehouse for unloading by a susceptible worker. Infection risks resulting exclusively from fomite transmission were simulated as contacts between the susceptible worker’s fingers and palms (of both hands) and the fomite surface (accounting for the surface area of the hand relative to the fomite surface); virus transfer from fomite to hands; and virus transfer from fingertips to facial mucous membranes (accounting for the surface area of the fingers relative to the combined surface area of the eyes, nose, and mouth). Grey boxes indicate infection control measures implemented for the infected (mask use, vaccination) and susceptible (handwashing, mask use, vaccination) workers. In the scenarios with additional plastic surface decontamination, this was simulated prior to the susceptible worker contacting the fomites.

A conceptual framework for fomite-mediated SARS-CoV-2 transmission involving exposure of a susceptible worker to individual plastic cartons, palletized cartons, and plastic wrap in a receiving warehouse under cold-chain conditions. This schematic depicts a representative frozen food packaging facility, initiating with two infected workers (left panel). Up to 10 contamination events per infected worker (0 to 10 coughs) can occur at three stages in the packaging pipeline: 1) contamination of the top-face of individual plastic cartons (144-216 individual cartons processed per hour) via respiratory droplet and aerosol fallout from the first infected worker while cartons are transported along a conveyor belt (orange in schematic); 2) contamination of cartons via respiratory particle spray (droplets and aerosols) as cartons are placed (manually or via automation) on a pallet by the second infected worker (yellow in schematic); and 3) contamination of the plastic-wrapped palletized cartons by respiratory particle spray (droplet and aerosol) from the second infected worker (yellow in schematic). Four pallets, each containing approximately 36-54 individual plastic cartons, are processed per hour. Because of current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP), the model did not account for indirect transfer of virus from the infected workers’ hands to the plastic fomites along the packaging pipeline. Under cold-chain conditions assuming no viral decay, plastic wrapped pallets were transported to a receiving warehouse for unloading by a susceptible worker. Infection risks resulting exclusively from fomite transmission were simulated as contacts between the susceptible worker’s fingers and palms (of both hands) and the fomite surface (accounting for the surface area of the hand relative to the fomite surface); virus transfer from fomite to hands; and virus transfer from fingertips to facial mucous membranes (accounting for the surface area of the fingers relative to the combined surface area of the eyes, nose, and mouth). Grey boxes indicate infection control measures implemented for the infected (mask use, vaccination) and susceptible (handwashing, mask use, vaccination) workers. In the scenarios with additional plastic surface decontamination, this was simulated prior to the susceptible worker contacting the fomites.

Study findings

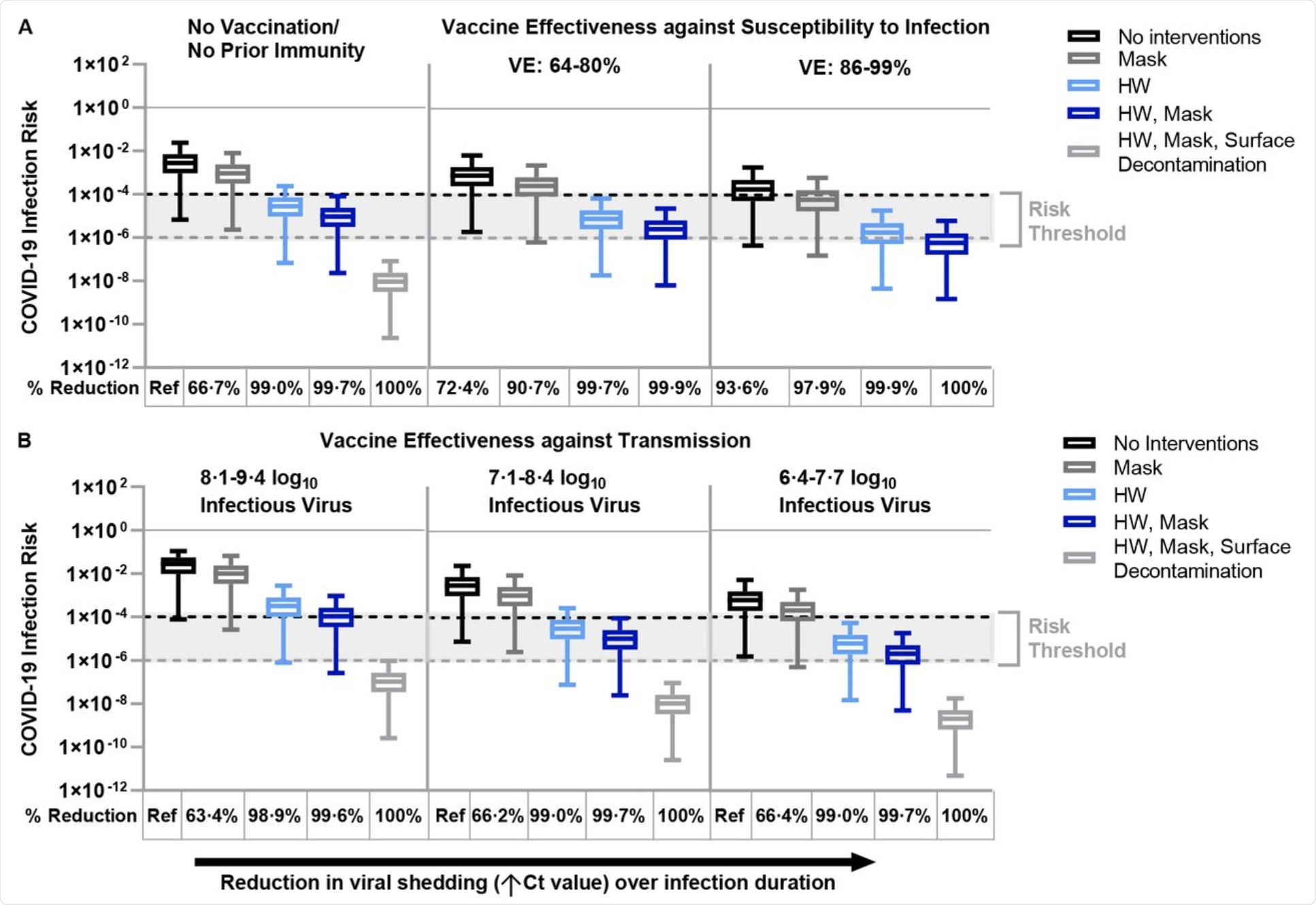

The researchers of the current study found that the risk of being infected while unpacking products in a cold chain in an individual who has no history of vaccination or infection is 2·8 x 10-3 per hour. This was reduced to a third by masking and further reduced to 1% by handwashing.

When both of these protective measures were utilized, the risk was reduced to almost zero when compared with when no measures were used. If plastic surfaces were decontaminated as well, the risk was reduced to below baseline.

Vaccination with two doses of a messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine reduced the risk of infection by up to 96% under optimal conditions or at least 72% with reduced vaccine efficacy. If mask-wearing, hourly handwashing, or both were adopted, the risk was reduced by 91%, 99.7%, and 99.9%, respectively, when compared to the unvaccinated state.

Under optimal conditions, vaccine protection, in addition to other measures, amounted to 93.6%, 98%, and 99.9% protection against SARS-CoV-2. Almost complete protection was afforded by combining masks with handwashing and vaccination under optimal or suboptimal conditions.

Taken together, a combination of non-vaccine measures including handwashing and mask-wearing ensures infection risk control. However, when vaccination is also carried out, the risk is less than one in a million.

With breakthrough infections caused by variants of concern (VOC), viral shedding may be higher. Even so, the aforementioned conclusion remains valid with up to a two-fold increase in the shedding of viral particles, with the risk being below the threshold of transmission. A small increase in risk was observed only when the VOC increased viral shedding by a hundred-fold.

Fomite-mediated SARS-CoV-2 infection risks associated with individual and combined standard infection control measures (hourly handwashing [2 log10 virus removal efficiency],58 surgical mask use). Vaccination was incorporated into the model representing two doses of mRNA vaccine (Moderna/Pfizer) and was applied with and without the standard infection control measures. Additional decontamination of plastic packaging [3 log10 virus removal efficiency]59 was applied in combination with the standard infection control measures.

Fomite-mediated SARS-CoV-2 infection risks associated with individual and combined standard infection control measures (hourly handwashing [2 log10 virus removal efficiency],58 surgical mask use). Vaccination was incorporated into the model representing two doses of mRNA vaccine (Moderna/Pfizer) and was applied with and without the standard infection control measures. Additional decontamination of plastic packaging [3 log10 virus removal efficiency]59 was applied in combination with the standard infection control measures.

Implications

These findings corroborate earlier studies that found very low infection risks from hand-to-fomite contact in the absence of surface disinfection.

“Given that the risk of fomite-mediated SARS-CoV-2 infection using standard infection control measures is so low, the benefit of decontaminating plastic packaging seems nominal and might be considered excessively conservative… and is more likely to increase chemical risks to workers, food hazard and quality risks to consumers, and unnecessary added costs to governments and the global food industry.”

Disinfectants are themselves associated with adverse health outcomes including asthma exacerbations and chronic obstructive lung disease among users.

In case of damage to the packaging, such disinfectants could enter the products and reach the consumers, causing potential irritation of the skin and eyes, mucous membranes of the nose and sinuses, along with dizziness, skeletal damage, or liver injury.

Moreover, surface disinfection delays food distribution and could jeopardize food chain stability or cause food spoilage. Finally, these processes ultimately can increase the costs of food products.

Reassuringly, the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant, which is 40-60% more transmissible than the Alpha variant, does not appear to pose a higher risk if these measures are followed. Thus, the virus is unlikely to be seeded into areas naïve for the infection, even when a highly infectious variant is in circulation.

“It is important to note that while the global vaccine rollout continues, maintaining high compliance with mask use and handwashing will be critical given their relatively low cost, high-impact risk mitigation potential, and ease of scaling across diverse food manufacturing settings.”

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Sobolik, J. S., Sajewski, E. T., Jaykus, L., et al. (2021). Low Risk Of SARS-Cov-2 Transmission Via Fomite, Even In Cold-Chain. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2021.08.23.21262477. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.08.23.21262477v1.

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Sobolik, Julia S., Elizabeth T. Sajewski, Lee-Ann Jaykus, D. Kane Cooper, Ben A. Lopman, Alicia N. M. Kraay, P. Barry Ryan, Jodie L. Guest, Amy Webb-Girard, and Juan S. Leon. 2022. “Decontamination of SARS-CoV-2 from Cold-Chain Food Packaging Provides No Marginal Benefit in Risk Reduction to Food Workers.” Food Control 136 (June): 108845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2022.108845. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S095671352200038X.