Analyses of over 100 viral genomes, including those from humans, pangolins, civets, and bats, revealed that the most common ancestor of all tested Sarbecovirus strains, a probable generalist mammalian pathogen, already had the necessary traits to infect humans and did not acquire them from other closely related strains. While inconclusive, this research presents a crucial first step in understanding this devastating pathogen's evolutionary history.

A Brief History of SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a positive single-sense RNA virus belonging to the Family Coronaviridae, subgenus Sarbercovirus. First discovered in Wuhan, China, in late 2019, the highly transmissible respiratory pathogen rapidly spread across the world, claiming almost 7 million human lives and infecting over 700 million more.

The now infamous coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is thus one of the worst in human history, but it is alarmingly not alone. In the past 18 years, two major coronavirus epidemics have preceded COVID-19 – the SARS-CoV-1 epidemic (China, 2002) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) epidemic (Saudi Arabia, 2012). Research has aimed to unravel the evolutionary origins of these pathogens, especially their severe infectivity, to improve current clinical interventions and better prepare against future outbreaks. Unfortunately, hitherto, these efforts have remained futile.

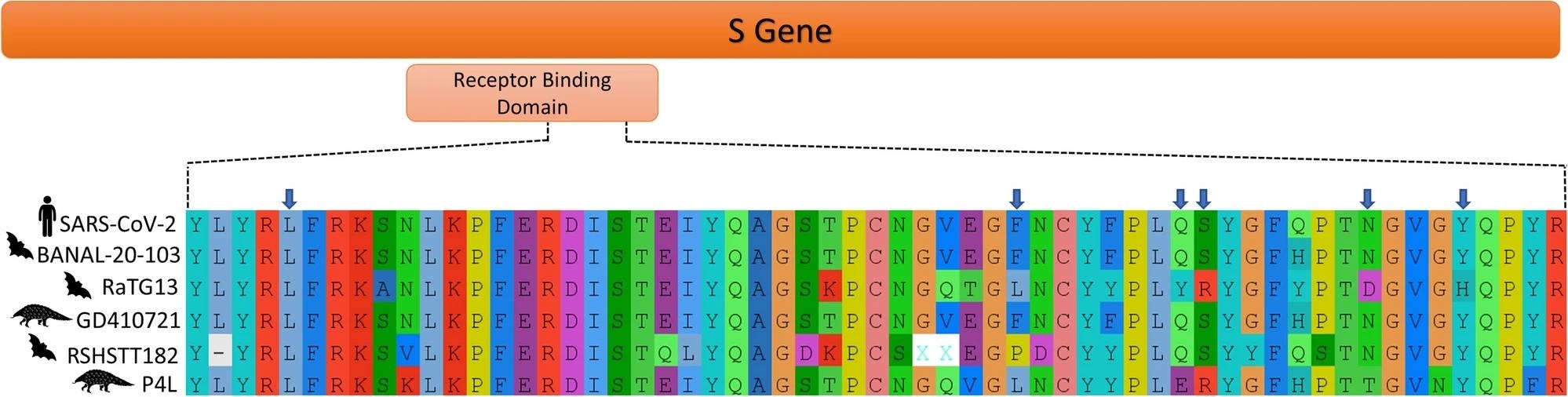

Amino acid residues present in the variable loop of the receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses. Amino acid residues important for the recognition of hACE2 receptor in SARS-CoV-2 are indicated with the blue arrows.

Amino acid residues present in the variable loop of the receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses. Amino acid residues important for the recognition of hACE2 receptor in SARS-CoV-2 are indicated with the blue arrows.

From the epidemiological lens, the most critical part of the 30 kb long SARS-CoV-2 genome is that part that codes for the spike protein, which in turn contains the receptor binding domain (RBD) – the mode of entry of the virus into its host cells. Both SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins have an affinity for the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (hACE2) receptor, with the latter having six amino acid (aa) residues essential for hACE2 receptor binding. Together, these six amino acids comprise the 'variable loop,' the most genetically diverse part of coronavirus genomes and the determinant of their host range.

Previous genomic analyses of SARS-CoV-2 have revealed that, while the overall genome of the pathogen is most closely related to bat coronaviruses, the RBD variable loop finds its nearest relative in a pangolin Sarbecovirus. These findings have prompted three of the four current hypotheses about the origin of the variable loop to invoke recombination. Recombination is the process by which viral genomes are transferred from one virus strain to another closely related strain, often during co-infection of a shared host. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, these hypotheses postulate that the variable RBD region was acquired from pangolins or bats.

The final hypothesis, however, challenges the recombination theory and postulates that the commonly observed affinity for the hACE2 receptor in many coronaviruses is due to convergent evolution. Understanding the evolutionary history of these viruses might aid in the next generation of anti-coronavirus vaccine development and help clinicians prepare for the next outbreak.

About the study

The present study aimed to elucidate the evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 RBD using the Bacter package in the BEAST2 phylogenetic software. The package enables the estimation of Ancestral Conversion Graphs (ACGs), a particular type of Ancestral Recombination Graphs (ARGs), the latter of which are the ideal tests for recombination but historically notoriously hard to compute.

Study data was obtained from the GenBank and the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) databases and consisted of 111 coronavirus genomes. The genomes included representation for humans (including a SARS-CoV-2 sequence sampled from Wuhan at the start of the pandemic), pangolins (N = 13), civets (N = 3), and bats (N = 93). Obtained sequences were cleaned and aligned with one another to obtain a 744 bp long RBD alignment.

Phylogenetic analyses comprised substitution model assessment and tree prior selection, followed by temporal signal testing. Finally, molecular dating analyses and Bayesian recombination analyses (using Bacter) were independently conducted, and their results were compared to elucidate if hACE2 affinity in coronavirus RBDs is a product of recombination or convergence.

Key findings

The recombination-aware phylogenetic analyses carried out herein comprised 111 coronavirus genomes from 45 Sarbecoviruses across human, bat, pangolin, and civet hosts. When discussing the phylogenetic analyses in isolation, multiple recombination events involving bat Rhinolophus species(R. sinicus, R. pusillus, and R. affinis) were observed. Notably, these three species with overlapping geographical ranges have been hypothesized as hosts for potential SARS-CoV-2 progenitors. Evaluations of the viral genomes of these bat pathogens lend support to the belief that recombination may have allowed human SARS-CoV-2 the ability to bypass host immunity, thereby contributing to severe virulence.

ASR analyses, however, support a non-recombinant origin for the RBD variable loop and demonstrate that the most common ancestor of human and bat coronaviruses had all the traits (amino acid residues) required for infectivity of both hosts, with the bat population losing all but one of these residues which the human-infecting virus retained.

"This ancestral virus was likely a generalist pathogen capable of infecting different types of mammalian hosts, since laboratory studies have proved that SARS-CoV-2 can bind to the ACE2 receptors of cattle, cats and dogs. The ability to bind to the hACE2 receptor has also been proposed as an ancestral trait of the whole Sarbecovirus subgenus, as the basal Sarbecovirus Khosta2, discovered in Russia, has shown this capacity in vitro."

While recombination cannot yet be disproved as the origin of the variable loop in human COVID, adaptation and convergence are the more parsimonious explanations for these traits. The results of the present study support the RBD variable loop's natural emergence in SARS-CoV-2.

"Our simultaneous estimation of the vertical (tree-like) and horizontal (recombination) evolutionary history of the virus is in stark contrast to the more traditional approach that consists in the initial detection of recombination breakpoints followed by the phylogenetic reconstruction of each region located between breakpoints. While we recognize that the computational requirements of the employed approach restricted the scope of this study, as we couldn't analyze the full data set and only analyzed a small fragment of the Sarbecovirus genome, we believe that the results obtained here provide an important "in-depth look" into the recombination history of the RBD."

Journal reference:

- Esquivel Gomez, L. R., Weber, A., Kocher, A., & Kühnert, D. (2024). Recombination-aware phylogenetic analysis sheds light on the evolutionary origin of SARS-CoV-2. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 1-11, DOI – https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50952-1, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-50952-1