By Sam McKenzie

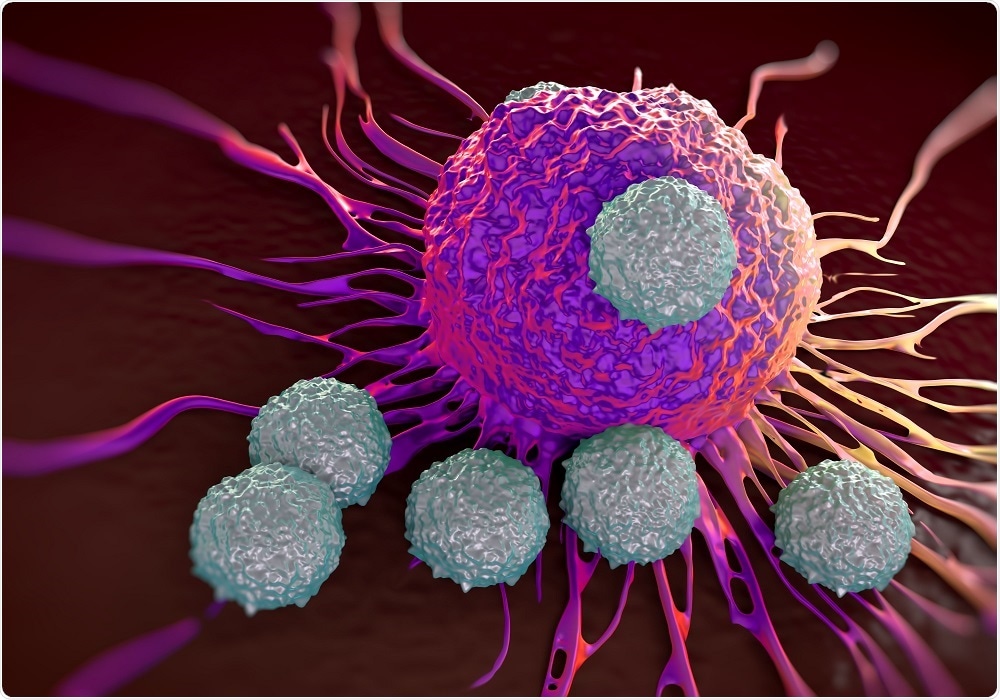

Immunotherapy involves the modification of immune cells to stimulate an immune response for the treatment or prevention of disease. In the case of cancer therapies, the aim is to induce an immune response that targets and kills the cancerous cells whilst avoiding damage to healthy cells.

Image Credit: royaltystockphoto / Shutterstock

Image Credit: royaltystockphoto / Shutterstock

There are two types of T cells (CD4+ and CD8+). CD8+ T-cells recognize foreign or pathogen-derived proteins called antigens. These pathogens are processed by antigen presenting cells into peptides and presented on molecules called major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs). This allows T-cells to induce an immune response.

T-cell receptors (TCRs) have different affinities for different antigen peptides. Only TCRs with a high affinity will induce an immune response. Natural anti-cancer TCRs have low affinity so methods to generate TCRs with a higher affinity to cancerous cells must be used.

Using therapeutic T-cells for cancer immunotherapy isn’t straightforward. For the therapy to be an effective form of treatment, T-cells must be:

- Trafficked to the site of a tumor

- Overcome immunosuppression

- Target all tumor cells

- Not affect healthy tissues

- Safe for use on a wide range of patients

This may seem like a tall order, but recent advances in synthetic biology and genome editing offer great potential to solve these problems.

Recent studies have investigated the ability to design a CD8+ T-cell that can target and kill cancerous cells efficiently.

A method that increases the affinity of TCRs involves displaying a library of TCRs on the surface of a bacteriophage, then performing several rounds of precise selection using immobilized peptide-MHC complexes. This increases the affinity of TCRs by directing the evolution of them to increase the TCR-peptide-MHC affinity.

In the thymus, immature T-cells undergo various stages of development and can become CD8+ T-cells. These T-cells interact with self-antigens and MHCs. T-cells with affinity too high are destroyed and ones with too low affinity die.

Another method used to generate higher affinity anti-cancer T-cells is to bypass the thymic selection stage of T-cell development. These T-cells have not undergone clonal selection, and thus comprise high affinity cancer-specific TCRs.

This has previously been achieved through the generation of ‘humanized’ mice which express a mouse MHC allele and the human TCR. Since these mice contain no human antigens, the human reactive TCRs are not deleted.

Modifying T-cells to target cancer cells can provide an alternative to existing cancer immunotherapies, such as checkpoint inhibitors. However, more research is needed in the field of T-cell immunotherapy in order to develop efficacious, targeted cancer therapies.