Among the hundred million or so cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) that have occurred since the pandemic began, pregnant women have been a conspicuous risk group. However, the exact nature of the risk they and their fetuses face, and the mechanism by which it operates, is far from clear. A new preprint research paper posted to the medRxiv* server throws some light on this area by revealing the presence of significant inflammation at the maternal-fetal interface.

The study included 39 pregnant women with COVID-19, as diagnosed by the reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) test for the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the agent that causes this infection.

Of the 15 placentas tested by RT-PCR, only two showed the presence of viral RNA. One of these has already been the subject of an earlier paper and was not included in further analyses.

The rate of placental infection seemed to be due to low levels of the viral receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), in term placentas. However, in contrast to the gene expression level, which showed low ACE2 mRNA, the actual ACE2 protein was found to be highly expressed in the placenta in the first and second trimesters, within the syncytiotrophoblast cells.

However, ACE2 levels were substantially higher in term placentas from women infected with COVID-19. Therefore, the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection of the placenta is highest in the first and second trimesters.

Cytotrophoblasts infected in vitro

By in vitro experiments, they sought to establish the possibility of infection of trophoblast cells. They found that primary isolated syncytiotrophoblasts were resistant to infection, but not primary isolated cytotrophoblasts. Nonetheless, most pregnant women with COVID-19, including women with high viral loads in the nasal mucosa or with symptomatic or even severe infection, typically did not have a detectable infection of the placenta.

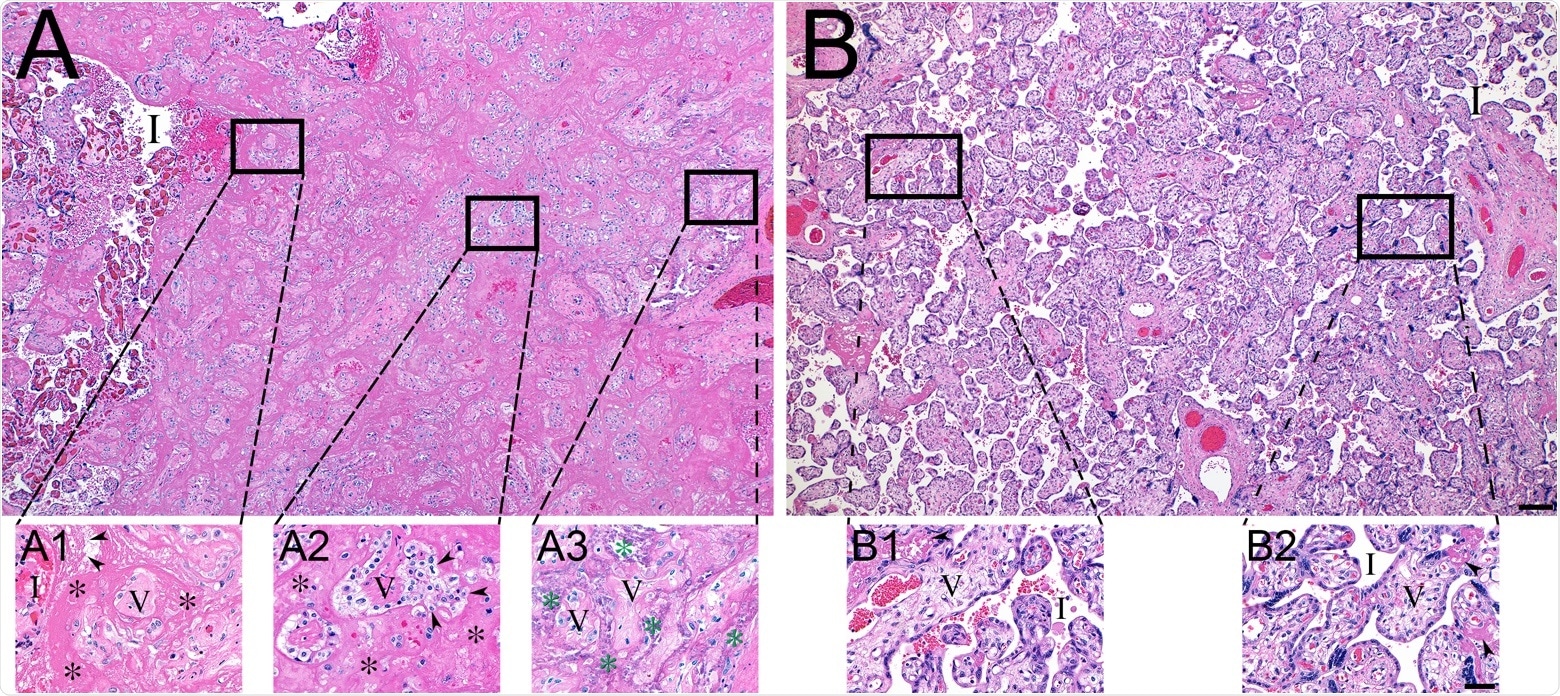

Histopathology of representative COVID-19 (A) and matched control (B) placentas. (A) COVID-19 placenta at low magnification revealed extensive intervillous fibrin deposition, with only occasional areas of open intervillous (I) spaces. (A1) High magnification at the edge of blood-filled intervillous space (I) and the earliest fibrin deposition (asterisks). Trapped chorionic villi (V) have become avascular and fibrotic. Initial fibrillar fibrin (arrowheads) can be seen at the blood-fibrin interface. (A2) The older area of intervillous fibrin (asterisks) and trapped villi (V) revealing the migration of trophoblasts (arrowheads) into the fibrin matrix. (A3) The oldest area of intervillous fibrin became calcified (green asterisks), encasing villous remnants (V). (B) In sharp contrast, the control placenta revealed virtually no fibrin in the intervillous space (I). (B1 and B2) Representative magnified areas revealed normal villi (V) and open, maternal blood containing intervillous space (I), with only occasional foci of fibrin formation (arrowheads). Bars represent 200 μM for images A and B and 50 μM for images A1-B2.

Immune genes overexpressed in COVID-19 placentas

The researchers thus looked for differences in placental gene expression to explain the presence of a localized and specific placental response to the virus in the absence of placental infection. Interestingly, they found gene markers of immune response to be increased in the placenta. The most prominent was the HSPA1A gene, which encodes the heat shock protein Hsp70, which may act as an alarmin in placental vasculitis and pre-eclampsia.

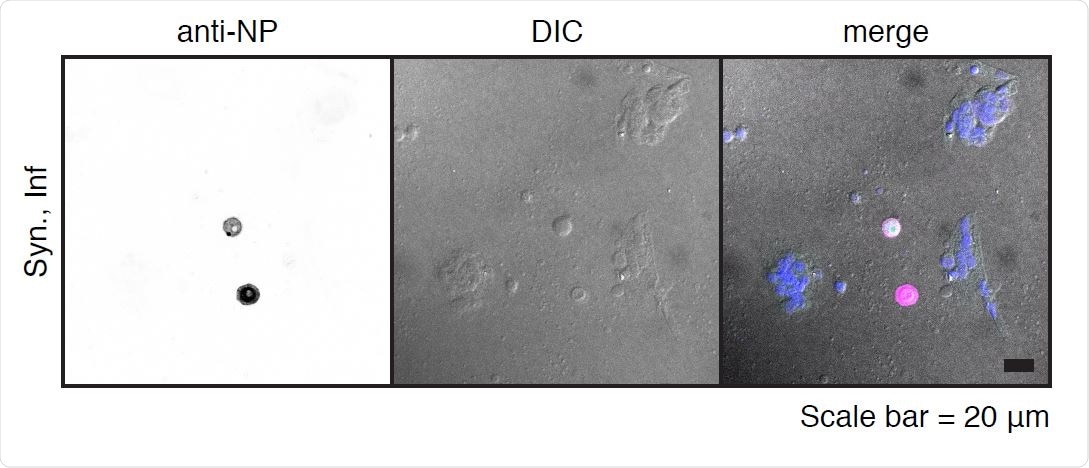

SARS-CoV-2 infection of primary syncytiotrophoblasts. Primary syncytiotrophoblasts were derived from primary isolated cytotrophoblasts allowed to spontaneously differentiate for 72-96 hours. Following the differentiation period, cells were infected at an MOI of 5 for one hour and washed three times with PBS before the addition of fresh media. Shown are two individual cells as detected by immunofluorescence following staining with anti-NP antibody (left panel). Differential interference contrast (DIC, center panel) image shows these two cells are excluded from the surrounding syncytia. Merged image (right panel) shows pseudocolor labeling of syncytialized cells in purple and infected NP-labeled individual cells in pink.

Cell-specific differences in transcription

The investigators further carried out single-cell RNA sequencing of 21 different cell types in the placenta. The analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) revealed proinflammatory genes and chemokines to be much higher in placentas from COVID-19 cases. This difference was observed in both immune and non-immune cell types.

T cell activation marker CD69, growth factors promoting tissue repair, ISG15, which is an interferon-stimulated gene central to antiviral responses in the host, as well as key chemokines involved in the NF-KB pathway, were all overexpressed in these placentas. These changes occurred in placental natural killer (NK) cells concerned with innate immunity, T cells, endothelial cells.

They also found that the alternative co-entry receptor for SARS-CoV-2, namely, CTSL, was extensively expressed in the placenta, unlike either ACE2 or the host protease implicated in viral entry, TMPRSS2.

The important role played by interferons in driving placental inflammation was also evident, since interferon-associated genes were strongly expressed in COVID-19 vs. control placental cells. HSPA1A levels were also high.

The highest increase in the number of immune cell interactions was observed at the maternal-fetal interface in COVID-19 placentas, especially T cells with monocytes and NK cells.

This suggests "innate to adaptive immune cell communication in the local placental environment during maternal COVID-19."

What are the implications?

The study results show that SARS-CoV-2 can infect one cell type in the placenta, but that placental infection itself is rare. Secondly, even without the virus's presence in the placental tissue, maternal COVID-19 appears to trigger a strong maternal immune response.

Though ACE2 is constitutively low in the placenta at term, it is high in the first and second trimesters, indicating that this is the period of most significant risk from this virus. However, mothers with COVID-19 had higher ACE2 levels in their placentas at term, perhaps because the receptor is upregulated during inflammation, as seen in other conditions.

Thirdly, the marked local DEG profile indicates a significant immune response in the placenta with maternal COVID-19, demonstrated at the maternal-fetal interface. The enrichment of this subset of genes for interferon-regulated genes shows the placental organ's ability to both detect and respond to local or systemic infection.

The elevation of HSPA1A expression in the placenta during COVID-19 is surprising and may suggest that this condition operates via a common pathway as placental vascular disease. This is because of the high levels of this protein Hsp70 in patients with endothelial activation due to vascular disease of the placenta, including pre-eclampsia.

Hsp70 is still higher when pregnant women have pre-eclampsia coupled with HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets) syndrome. Thus, further research is required to delineate the final pathway resulting from either placental vascular disease and severe COVID-19 in pregnancy.

The increased deposition of fibrin in the placenta's intervillous space suggests decreased perfusion of the maternal side, increased coagulability, and reduced thrombolysis. The researchers suggest some possible implications. Either the maternal endothelium is activated by COVID-19, with a localized drop in fibrinolysis. Another line of thought is that procoagulant activity in the placenta is triggered by immune cell activation and circulating inflammatory cytokines. This causes the syncytiotrophoblasts to secrete tissue factor, causing fibrin build-up. This is supported by the findings that the expression of NK cell and endothelial cell genes implicated in such pathways is increased.

"Our research indicated that maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection at term is associated with an inflammatory state in the placenta that may contribute to poor pregnancy outcomes in COVID-19, even in the absence of viral invasion of the placenta."

While these may be protective, sealing the fetus off from infection along with the placenta, they could also be harmful.

For one, they may cause adverse development of the neural system or fetal demise as seen in mouse studies. More research will be needed to identify the long-term results of such immune activation and inflammation in maternal COVID-19.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Lu-Culligan, A. et al. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy is associated with robust inflammatory response at the maternal-fetal interface. medRxiv preprint. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.25.21250452, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.01.25.21250452v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Lu-Culligan, Alice, Arun R. Chavan, Pavithra Vijayakumar, Lina Irshaid, Edward M. Courchaine, Kristin M. Milano, Zhonghua Tang, et al. 2021. “Maternal Respiratory SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Pregnancy Is Associated with a Robust Inflammatory Response at the Maternal-Fetal Interface.” Med 2 (5): 591-610.e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medj.2021.04.016. https://www.cell.com/med/fulltext/S2666-6340(21)00165-3.