Introduction

What is PFD?

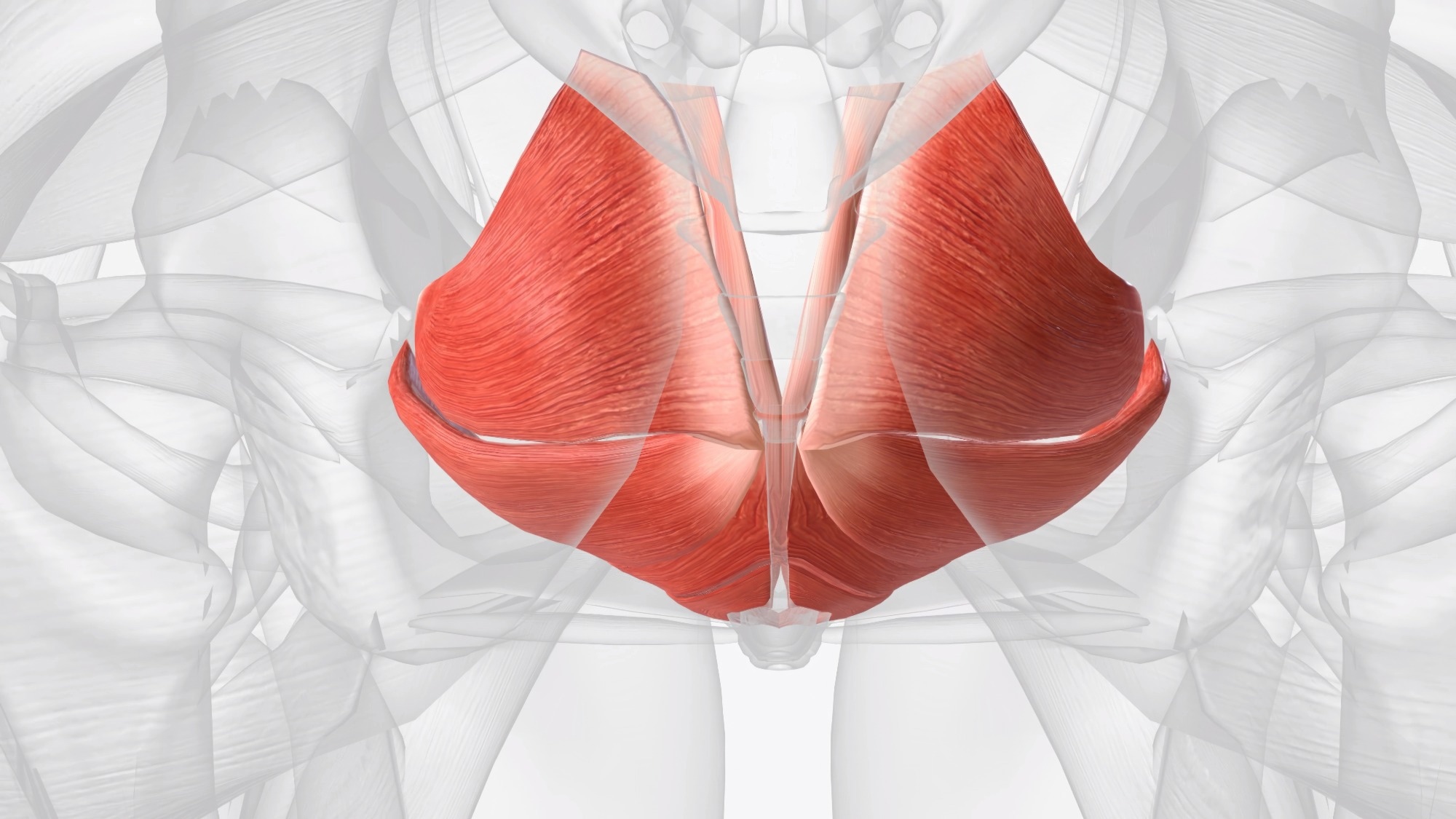

Anatomy and physiology refresher

Types of PFD

Impacts on health

Risk factors for PFD

Diagnosis and assessment

Treatment and management

Conclusions

References

Further reading

When the pelvic floor’s intricate support system falters, everyday activities and continence are compromised, but advancing diagnostics and targeted therapy offer renewed stability.

Image Credit: H_Ko / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: H_Ko / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

The present article reviews the intricate anatomy of the pelvic floor and its coordinated physiology, as well as the profound impact of pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) on bladder, bowel, and sexual function. PFD encompasses a range of muscular and connective tissue disorders affecting bladder, bowel, and sexual function, with significant quality-of-life and clinical implications. Early diagnosis and individualized management can reduce long-term complications and improve outcomes.

What is PFD?

The pelvic floor is an anatomical region in the human body, comprising muscles, ligaments, and fascia.1 Decades of research have revealed that the pelvic floor provides vital organ support, maintains continence, and contributes to sexual function.1,2

PFD is an umbrella term encompassing several disorders that occur when these muscles fail to coordinate correctly and, as a result, lead to symptoms affecting bladder, bowel, and sexual health.2 PFD is recognized as a public health concern in women, with contemporary estimates indicating that roughly one quarter of adult women are affected, although prevalence varies by population and case definition.3,4

Extensive health-system data suggest that approximately one-third of adult women seen in primary care carry at least one PFD diagnosis, with bowel dysfunction the most common, followed by urinary incontinence and POP.4 Underdiagnosis is common; many affected individuals delay presentation for care.7

PFD also occurs in men in the context of urologic and pain syndromes such as chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS), where sexual dysfunction (e.g., erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation) is frequently reported.6

Anatomy and physiology refresher

The pelvic floor is a multi-layered, dome-shaped muscular sheet suspended within the pelvis.1-3 The primary supportive layer, known as the ‘levator ani’, maintains a constant tonic contraction to support the bladder, uterus, prostate, and rectum against intra-abdominal pressure.2,3

The puborectalis forms a critical U-shaped sling around the anorectal junction that is essential for fecal continence.3 Innervation is derived mainly from the pudendal nerve (S3–S4) with somatic input to the striated musculature; autonomic inputs modulate anorectal tone and reflexes.1,2

The pelvic floor functions in concert with the abdominal wall and respiratory diaphragm to regulate intra-abdominal pressure during activities such as coughing and defecation.1,2

Image Credit: benoted / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: benoted / Shutterstock.com

Types of PFD

PFD can be further characterized based on the presence of hypertonic or hypotonic muscle tone within the pelvic floor.3 A hypertonic pelvic floor is described as excessively tight and unable to fully relax, which leads to obstructive symptoms, pelvic pain, and dyspareunia. Conversely, a hypotonic pelvic floor is weak and lacks adequate tone, thereby resulting in stress incontinence and POP.1,3

Pelvic floor muscles can be both tight and weak due to poor motor power and limited range of motion.3 This distinction is vital, as strengthening exercises appropriate for hypotonicity can exacerbate hypertonic conditions, which emphasizes the importance of personalized interventions to target these conditions.1-3,5

POP, which refers to herniation of pelvic organs into the vaginal canal due to the failure of muscular and fascial supports, is one of the most widely studied forms of PFD.8 POP-Q system, with Stage 0 for no prolapse to complete eversion in Stage IV.8

Childbirth-related mechanical and neuromuscular trauma, particularly to the levator ani, is a major contributor to postpartum PFD risk; operative vaginal delivery, prolonged second stage, and obstetric anal sphincter injury further increase risk.7,10

Impacts on health

Hypotonicity increases the risk of stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Comparatively, hypertonicity may cause urinary urgency, frequency, and dysuria, or painful urination, which closely mimics a urinary tract infection.2

Within the gastrointestinal tract, hypotonicity can cause fecal incontinence. Comparatively, hypertonicity is the primary risk factor for obstructive defecation, during which the puborectalis muscle fails to relax, leading to chronic constipation.2

PFDs are associated with reductions in health-related quality of life across physical, social, emotional, and sexual domains; the burden is particularly marked with prolapse and colorectal-anal symptom subscales.3 Qualitative syntheses corroborate pervasive impacts on daily functioning, sleep, and sexual health.7

In men with CP/CPPS, sexual dysfunction is common, with pooled prevalence estimates of approximately 34% for erectile dysfunction and 35% for premature ejaculation.6

Risk factors for PFD

Ageing, higher body mass index, and higher parity are consistently associated with PFDs in epidemiological analyses; parity is especially associated with an increased risk of prolapse.4,8

Pregnancy and childbirth are the most significant risk factors for PFD in women, with vaginal delivery increasing the risk of PFD relative to cesarean delivery.8,10

Other factors that contribute to PFD etiology include the hormonal decline accompanying menopause, advancing age, and conditions that chronically elevate intra-abdominal pressure, like obesity, chronic cough, and constipation.2,7,8

Diagnosis and assessment

PFD diagnosis is a multistep procedure that involves a detailed review of the patient's clinical history and specialized physical examination to evaluate pelvic pressure and muscle strength.2 Validated patient-reported measures such as the PFDI-20 and its subscales (POPDI-6, CRADI-8, UDI-6) are frequently used to quantify symptom burden and functional impact.3

More complex PFD cases leverage objective data obtained from urodynamic studies, cystometry, and electromyography to improve diagnostic accuracy.2,8 PFD diagnosis may also utilize imaging modalities like ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to visualize anatomical defects and guide clinical interventions.2,5,8

Treatment and management

The clinically recommended first-line response for PFD is conservative management, which involves administering pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) to patients with hypotonic conditions. Nevertheless, a 2025 updated Cochrane review concluded that adding biofeedback to PFMT produces little to no difference in incontinence-specific quality of life and only a slight reduction in daily leakage episodes compared with PFMT alone.5

For the treatment of POP, vaginal pessaries are used to provide mechanical support and are considered an effective non-surgical option. For SUI, mid-urethral slings are considered a standard surgical procedure. Importantly, regulatory actions restricting transvaginal mesh for prolapse repair did not apply to mid-urethral slings for SUI.2,10

The use of surgical mesh for transvaginal POP repair, a frequently cited historical intervention, is associated with numerous complications, which have reduced its clinical use. In 2011, U.S. regulators communicated that serious adverse events with transvaginal mesh for POP were “not rare.” In 2019, the FDA ordered manufacturers to stop selling these devices for transvaginal prolapse repair due to insufficient evidence of superiority over native-tissue repair.10

As of 2019, the use of surgical mesh in transvaginal POP repair ended in the United States. However, abdominally placed mesh for sacrocolpopexy remains a safe and effective option for cases demonstrating apical prolapse.2,10

Conclusions

Effective PFD management requires a holistic, multidisciplinary approach that simultaneously addresses underlying musculoskeletal dysfunction and its associated psychosocial impacts. Routine case-finding in primary care and timely referral pathways are warranted, given the high prevalence and substantial quality-of-life implications.3,4

References

- Bharucha, A. E. (2006). Pelvic floor: anatomy and function. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 18(7); 507–519. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00803.x, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00803.x.

- Grimes, W. R., & Stratton, M. (2023, June 26). Pelvic floor dysfunction. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559246/

- Peinado Molina, R. A., Hernández Martínez, A., Martínez Vázquez, S., & Martínez Galiano, J. M. (2023). Influence of pelvic floor disorders on quality of life in women. Frontiers in Public Health 11. DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1180907, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1180907.

- Kenne, K. A., Wendt, L., & Brooks Jackson, J. (2022). Prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in adult women being seen in a primary care setting and associated risk factors. Scientific Reports 12(1). DOI:10.1038/s41598-022-13501-w, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-13501-w.

- Fernandes, A. C. N. L., Jorge, C. H., Weatherall, M., Ribeiro, I. V., Wallace, S. A., & Hay-Smith, E. J. C. (2025). Pelvic floor muscle training with feedback or biofeedback for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD009252.pub2, https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009252.pub2/full.

- Alshahrani, S., Fathi, B. A., Abouelgreed, T. A., & El-Metwally, A. (2025). Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunction with Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome (CP/CPPS): An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 61(6); 1110. DOI:10.3390/medicina61061110, https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/61/6/1110.

- Rodríguez-Almagro, J., Hernández Martínez, A., Martínez-Vázquez, S., et al. (2024). A Qualitative Exploration of the Perceptions of Women Living with Pelvic Floor Disorders and Factors Related to Quality of Life. Journal of Clinical Medicine 13(7); 1896. DOI:10.3390/jcm13071896, https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/13/7/1896.

- Iglesia, C. B., & Smithling, K. R. (2017). Pelvic organ prolapse. American Family Physician 96(3); 179–185. , https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2017/0801/p179.html.

- Herderschee, R., Hay-Smith, E. J. C., Herbison, G. P., et al. (2011). Feedback or biofeedback to augment pelvic floor muscle training for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD009252, https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009252.pub2/full.

- American Hospital Association. (2019). FDA orders surgical mesh for pelvic procedure off the market. AHA News. https://www.aha.org/news/headline/2019-04-16-fda-orders-surgical-mesh-pelvic-procedure-market. Accessed 10 October 2025

Further Reading

Last Updated: Nov 4, 2025