Conventional ultrasound (cUS) and functional ultrasound (fUS) both utilize megahertz-level sound waves to image inside the body; however, beyond this, the similarities end. This article aims to clarify the differences between the two techniques by examining the underlying technology. We then discuss the unique advantages of fUS compared to cUS and conclude with an explanation of why this makes fUS an ideal choice for functional imaging of blood flow in the brain.

Understanding ultrasound

Since its introduction as a clinical technique in the 1940s, ultrasound has established a firm place in the arsenal of diagnostic imaging techniques used by clinicians and researchers, due to its ability to non-invasively probe the inner structures of the body.

Although the principle of ultrasound is straightforward (see below), both the number and complexity of ultrasound modalities have increased substantially, with options such as B-mode, M-mode, pulsed-wave Doppler, color Doppler, and power Doppler familiar to many in the field.

This complexity can make it difficult to appreciate the advantages offered by a particular modality, or the applications for which it is best suited.

A case in point is the relatively new technique of functional ultrasound (fUS), which is used in Iconeus One and a small number of other systems on the market. In particular, it is not always easy to understand what differentiates it from conventional ultrasound (cUS), which is used in most ultrasound scanners.

This article explains how cUS and fUS work, and why only fUS provides the combination of sensitivity, temporal resolution, spatial resolution, and field of view that makes it ideally suited for imaging blood flow in the brain.

The essentials of conventional ultrasound

Conventional ultrasound scanners most commonly use a series of 128 (or 256) point-source transducers arranged over a length of about 5 cm. Each transducer emits an ultrasound pulse, with a slight delay between them so that the waves all reach the desired region at the same time.

This maximizes the strength of the echo from that focal region, providing a strong signal. If there are scatterers in the tissue, the echoes from them bounce back to the transducers. The signals from all the transducers are then processed to create a one-dimensional image line.

Typically, this process is repeated 128 (or 256) times, with a different time delay applied in each case, so that the ultrasound is successively focused from left to right. Usually, the entire series of acquisitions is carried out at four focal depths to ensure a well-resolved two-dimensional image slice across the whole region of interest.

The essentials of conventional ultrasound

Video showing the process of transmitting a focused ultrasound beam and recording the echoes from scatterers (black dots) using conventional ultrasound. The red lines indicate the region over which the ultrasound pulses are focused, with the narrow part indicating the region of greatest focus. A delay is applied to each received ultrasound signal to account for the time taken to reach that transducer, and the signals are then summed and processed to generate the first line. Video Credit: Iconeus

The unavoidable trade-off with conventional ultrasound

This approach is effective but sending and receiving all of these separate signals takes time. For example, a single transmit-receive pulse from a transducer takes 30 µs to reach a depth of 5 cm and another 30 µs to return.

If 128 transducers are used and data from four focal depths are combined, it takes 30 µs × 2 × 128 × 4 = 32 ms to acquire a single two-dimensional slice.

This places a limit on the rate of acquisition of two-dimensional frames, commonly referred to as the frame rate. Based on these calculations, this corresponds to 1/0.032 = 31 frames per second, or more generally, in the range of 25–50 frames per second.

This frame rate is sufficient for imaging tissues that move slowly, but for tissues that move much faster than a beating heart, this limitation becomes significant.

One solution is to collect data from only a contiguous subset of the transducers, reducing the time required to obtain a complete image.

For example, to achieve 250–500 frames per second at a depth of 5 cm, data would be collected from only one-tenth of the transducers, reducing the image width from 5 cm to 5 mm.

At the extreme, achieving a frame rate of approximately 5,000 frames per second requires collecting data from a single transducer, reducing the image width to just 0.5 mm, as in pulsed-wave Doppler.

Alternatively, data from all transducers can be used while limiting the focal depth, allowing more transmit-receive pulses to be packed into a given time. Either way, conventional ultrasound involves an unavoidable compromise between temporal resolution and field of view.

The role of plane waves and the link to ultrafast ultrasound

This trade-off can be overcome by firing all the transducers at once. This solution was proposed in the late 1990s and developed in subsequent years by a team involving Iconeus founder Mickael Tanter.1

This approach creates a plane wave, eliminating the time delay inherent in the transmit-receive pulse sequence and enabling what is known as ultrafast ultrasound.

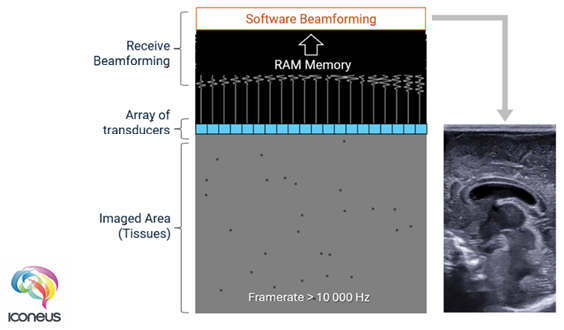

Because plane waves are unfocused, all scatterers produce echoes at approximately the same time. This combined signal is more difficult to process, and storing and processing this data in real time only became practical for 128-transducer arrays around 2016, with the advent of more powerful computer chips.

With modern parallel processing techniques, including those used in the software for Iconeus One, this complex data can be rapidly deconvolved to yield information on the position of all scatterers.

Principle of using plane-wave transmission to speed up imaging – a process that is at the core of ultrafast ultrasound, and hence of functional ultrasound. Image Credit: Iconeus

More importantly, plane-wave transmission dramatically reduces the time required for imaging. Typically, it takes just 0.1–0.5 ms to acquire a single two-dimensional slice, resulting in a frame rate of approximately 10,000 frames per second. This is about 200 times higher than that of conventional ultrasound.

Combining ultrafast ultrasound and signal processing to achieve fUS

Functional ultrasound builds on ultrafast ultrasound by combining plane-wave transmission with advanced signal processing. This enables the achievement of high temporal resolution and high spatial resolution across a region that is large enough to be diagnostically useful.

The unfocused nature of plane-wave ultrasound increases image noise, known as speckle, and reduces sensitivity.

A solution described in a 2011 paper and implemented in Iconeus One involves running each acquisition using a series of plane waves at slightly different angles and then summing them.2

This technique, known as coherent plane-wave compounding, cancels out a substantial proportion of background noise at the cost of a modest reduction in frame rate. Specifically, compounding N plane waves reduces the frame rate by a factor of N.

The number of compounded scans can be adjusted entirely in software, allowing it to be fine-tuned to the requirements of each application.

"Coherent plane-wave compounding"

Using coherent plane-wave compounding to increase the signal-to-noise ratio in functional ultrasound images – a process that can be considered to be a type of ‘virtual focusing’. Video Credit: Iconeus

The resulting increase in signal-to-noise ratio leads to higher sensitivity, which is further enhanced by improved signal processing.

Because all parts of the tissue are sampled simultaneously rather than at different points in time, pixel-to-pixel comparisons are more robust. Overall, fUS is approximately 100 times more sensitive than cUS, enabling the detection of much smaller movements.

Why ultra-high-frequency transducers cannot perform fUS

Throughout this discussion of image quality in functional ultrasound, the specifications of the transducer have not yet been addressed. In principle, increasing the ultrasound frequency should improve resolution by allowing smaller features to produce echoes.

In practice, higher frequencies are absorbed more strongly by tissue, resulting in poorer transmission and reduced imaging depth.

For most preclinical applications, whether using cUS or fUS, a transducer frequency of 15 MHz provides a good compromise between imaging depth and spatial resolution. This is the frequency used for most Iconeus transducers.

Although transducers used for conventional ultrasound could, in principle, be used with Iconeus One, overall performance and reliability considerations mean that the system is designed to accept only Iconeus transducers.

Ultra-high-frequency transducers marketed for use with conventional ultrasound and optoacoustics are rated up to 70 MHz. While these provide improved spatial resolution compared to conventional transducers, signal attenuation limits them to resolving features within only the first few millimeters of the surface.

They also suffer from the same compromise between temporal resolution and field of view that affects all conventional ultrasound systems. As a result, although ultra-high-frequency transducers are useful for certain niche applications, they cannot achieve the wide-range functional imaging offered by fUS.

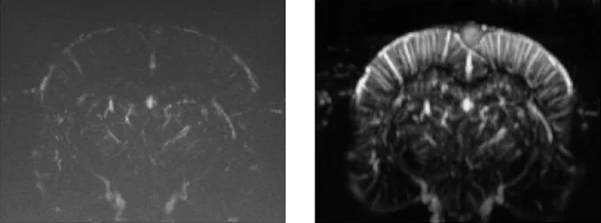

Indicative comparison of the imaging performance that can be achieved using cUS (left) and true fUS (right) for the rat brain (here involving a craniotomy), in both cases carried out by adjusting the scan settings on Iconeus One. fUS clearly has an advantage over cUS in terms of resolution and sensitivity. Image Credit: Iconeus

Why is fUS primarily used for brain imaging?

The applications of conventional ultrasound are well established, with pregnancy monitoring being the most widely recognized, alongside routine investigations of the heart, eyes, and breast.

In principle, functional ultrasound can be used to image these tissues as well, and the ultrafast ultrasound technique that underpins fUS was originally developed for tumor imaging.

The advanced hardware and software required for fUS, however, make it most suitable for applications that cannot be adequately addressed using conventional ultrasound.

Conventional ultrasound is particularly limited when imaging blood flow, especially low flows below 2 cm/s. This limitation arises because the relatively low frame rate of cUS restricts motion separation to simple high-pass filtering.

While the filters themselves are effective (they can actually work fine with fUS data), the combination of filtering and low frame rate makes it impossible to remove signals from slow tissue motion while preserving information from slowly moving blood cells.

Even in arteries, where blood flow can approach 1 m/s, the switch to low flows during the diastolic phase usually means that this phase is not well-imaged.

In contrast, the complete spatial and temporal coverage provided by ultrafast ultrasound enables a more effective method for separating fast and slow movements, known as singular value decomposition (SVD).

SVD filtering separates highly coherent, large-scale tissue motion from the more complex, decorrelated fluctuations produced by blood flow, allowing slow tissue movements to be removed while preserving hemodynamic information.

The lower detection limit for blood flow remains 1 mm/s, the same as for cUS, but fUS achieves this sensitivity across the entire brain rather than at a single point.

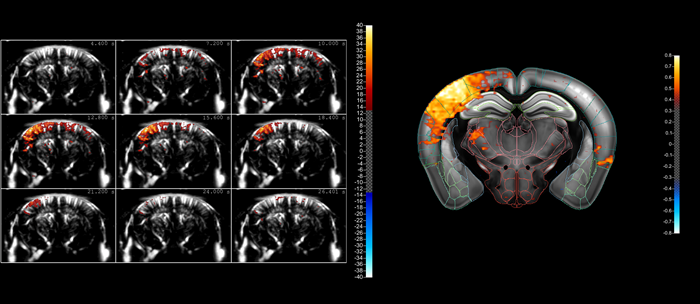

Such low flows are characteristic of the smallest blood vessels, particularly arterioles in the brain, where blood flow increases in response to neuronal activation through a process known as neurovascular coupling.

By monitoring these blood flow changes using fUS, neuronal activation in specific brain regions can be inferred. This enables the study of sensory stimulation, functional connectivity, and disease mechanisms. Using Iconeus One, this can be achieved in real time.

A typical compiled sequence of images acquired using fUS, showing the ‘lighting up’ of a part of the mouse brain as a result of whisker stimulation. The fact that blood flows in the brain can be in different directions within a small volume means that it’s better to image this activity using blood volume (using Power Doppler) rather than blood velocity (using color Doppler). However, our fUS– and microbubble-enabled ultrasound localization microscopy (ULM) technique – allows the actual blood velocities to be determined at high resolution, should that information be needed. Image Credit: Iconeus

Toward the future of fUS

The unique capabilities of functional ultrasound, combined with strong research interest in brain science, have made it a valuable tool for brain researchers.3 As the technology matures, it is also attracting interest beyond academic research.

Collaborations with the pharmaceutical industry have explored fUS as an alternative to conventional fMRI, while research hospitals and clinics are investigating the translation of preclinical fUS methods from animal models to humans.

Transcranial fUS imaging of the brain microvasculature in adults (artist’s impression). Image Credit: Courtesy A. Dizeux/M. Tanter.

Functional ultrasound is therefore positioned at the forefront of brain imaging for scientific discovery, where it offers clear advantages over conventional ultrasound, which remains focused on routine diagnostics.

These advantages arise from the way ultrasound transducers are fired and the careful balancing of performance trade-offs.

They are the result of decades of optimization efforts led by experts in physics, signal processing, and neuroscience, many of whom are part of the team at Iconeus.

Ultrasound techniques compared

For ease of reference, below is an at-a-glance comparison of cUS and ultrafast US (the technology that underpins fUS). All values are approximate.

Source: Iconeus

| Category |

Conventional US |

Ultrafast US |

|

|

|

| Transducer frequency |

Usually 15 MHz (but up to 70 MHz for some applications) |

Usually 15 MHz (or a little lower for some applications) |

Ultrasound

transmission |

Focused on a region |

Unfocused plane wave |

Transducer transmit/

receive pattern |

Line-by-line focused acquisitions |

Full-field acquisition from each plane wave transmission |

| Temporal resolution |

32 ms |

0.1–0.5 ms |

| Frame rate |

25–50 frames/s |

Up to 10,000 frames/s (effective 500-2000 fps with compounding) |

Spatial resolution (for

a 15 MHz probe) |

∼100 µm |

∼100 µm (or 5 µm with ULM) |

| Doppler sensitivity |

Low sensitivity to

microvascular flow |

High sensitivity; detects ∼1 % flow variations |

| Clutter filtering |

Temporal high-pas filters

(Wall filters) |

SVD spatiotemporal filtering (coherent vs incoherent separation) |

Lowest detectable

blood velocities |

∼1-2 mm/s (limited by noise/clutter) |

∼0.5-1 mm/s (uniformly across the field) |

| Possibility of 3D (volumetric) imaging |

Yes, but mostly B-mode |

Yes, across all modes |

| Core applications |

Imaging soft tissues and blood flows in large vessels |

Functional imaging of blood flows in the brain and spinal cord |

References and further reading

- Sandrin, L., et al. (1999). Time-Resolved Pulsed Elastography with Ultrafast Ultrasonic Imaging. Ultrasonic Imaging, 21(4), pp.259–272. DOI: 10.1177/016173469902100402. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/016173469902100402.

- Macé, E., et al. (2011). Functional ultrasound imaging of the brain. Nature Methods, (online) 8(8), pp.662–664. DOI: 10.1038/nmeth.1641. https://www.nature.com/articles/nmeth.1641.

- Deffieux, T., et al. (2018). Functional ultrasound neuroimaging: a review of the preclinical and clinical state of the art. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, (online) 50, pp.128–135. DOI: 10.1016/j.conb.2018.02.001. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959438817302465?via%3Dihub.

About Iconeus

Iconeus is a Paris-based company, founded by the inventors of functional ultrasound, who have invented an easy-to-use functional ultrasound system for imaging cerebral blood flow and microvasculature. Its unique combination of sensitivity, speed and high resolution has enabled it to lead the field in preclinical studies on awake animals, and it is now being proposed for applications in clinical research too.

Iconeus is introducing functional ultrasound neuro imaging: a breakthrough imaging modality for brain activity monitoring based on blood flow imaging with ultra-high sensitivity.

For preclinical research, the portability and high versatility of their technology enables the study of brain activity at unprecedented scales and in a large variety of subject states: awake, behaving, freely-moving, resting-state and asleep conditions.

Iconeus' technology can be easily combined with other complementary modalities such as EEG headstage or optogenetics which are inherently difficult to combine with FMRI. Iconeus also offers key applications such as functional connectivity assessment between brain structures (connectomics) or stroke 4D monitoring. Building on years of preclinical expertise and research, they're now investing and supporting exciting new clinical applications.

Sponsored Content Policy: News-Medical.net publishes articles and related content that may be derived from sources where we have existing commercial relationships, provided such content adds value to the core editorial ethos of News-Medical.net, which is to educate and inform site visitors interested in medical research, science, medical devices and treatments.