What is histamine and how is it metabolized?

Proposed mechanisms behind histamine intolerance

Symptoms and overlap with other conditions

Current evidence and controversies

Diagnostic approaches and limitations

Management strategies

Conclusion: Real condition or misdiagnosis?

Caution against self-diagnosis without medical guidance

References

Further Reading

Could your unexplained symptoms be linked to histamine intolerance, or is it a misunderstood diagnosis? This article dives into the science, evidence, and ongoing debate.

Image Credit: Perfect Wave / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Perfect Wave / Shutterstock.com

Histamine intolerance (HIT), also termed enteral histaminosis or dietary histamine sensitivity, is frequently cited as a potential explanation for complex, multi-system symptoms that elude conventional diagnoses. By definition, HIT is a pathological imbalance between histamine intake and the body’s capacity to metabolize or break it down in the intestines, thereby leading to its accumulation and activation of histamine receptors across multiple organ systems.1

In susceptible individuals, even physiologically normal or low levels of dietary histamine may elicit gastrointestinal, dermatological, neurological, or cardiovascular manifestations. However, symptom heterogeneity and overlap with other non-immunological food sensitivities, combined with the absence of standardized diagnostic criteria and validated testing protocols, continue to obscure its classification.1,2

What is histamine and how is it metabolized?

Histamine is a bioactive amine essential for immune defense, gastric acid secretion, and neurotransmission. It exerts pleiotropic effects, including vasodilation, smooth muscle contraction, leukocyte chemotaxis, and cytokine modulation, making it central to both allergy and innate immunity.

In the stomach, histamine is released from enterochromaffin-like cells, which stimulates parietal cells to secrete acid. Gastric acid breaks down food, particularly proteins, activates digestive enzymes such as pepsin, and facilitates the absorption of calcium, iron, vitamin B12, and other essential nutrients.

In the nervous system, histamine acts as a neurotransmitter from hypothalamic neurons, wherein this molecule influences thermoregulation, alertness, appetite, and cognitive-behavioral functions.3,4

Histamine is endogenously formed by the decarboxylation of histidine, primarily in mast cells, basophils, gastric enterochromaffin cells, and histaminergic neurons. Exogenous sources include aged cheeses, fermented foods, alcohol, certain fish, as well as spinach, tomatoes, and other vegetables through microbial fermentation.4,5

DAO degrades extracellular histamine, whereas histamine N-methyltransferase (HNMT) inactivates histamine within cells. Monoamine oxidase (MAO) may also contribute to histamine metabolism. DAO, which is dependent on vitamin B6, vitamin C, and copper, is abundant in the intestines, placenta, and kidneys. HNMT is predominantly present in the liver, kidneys, and respiratory tract.2,5

Image Credit: Juan Gaertner / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Juan Gaertner / Shutterstock.com

Proposed mechanisms behind histamine intolerance

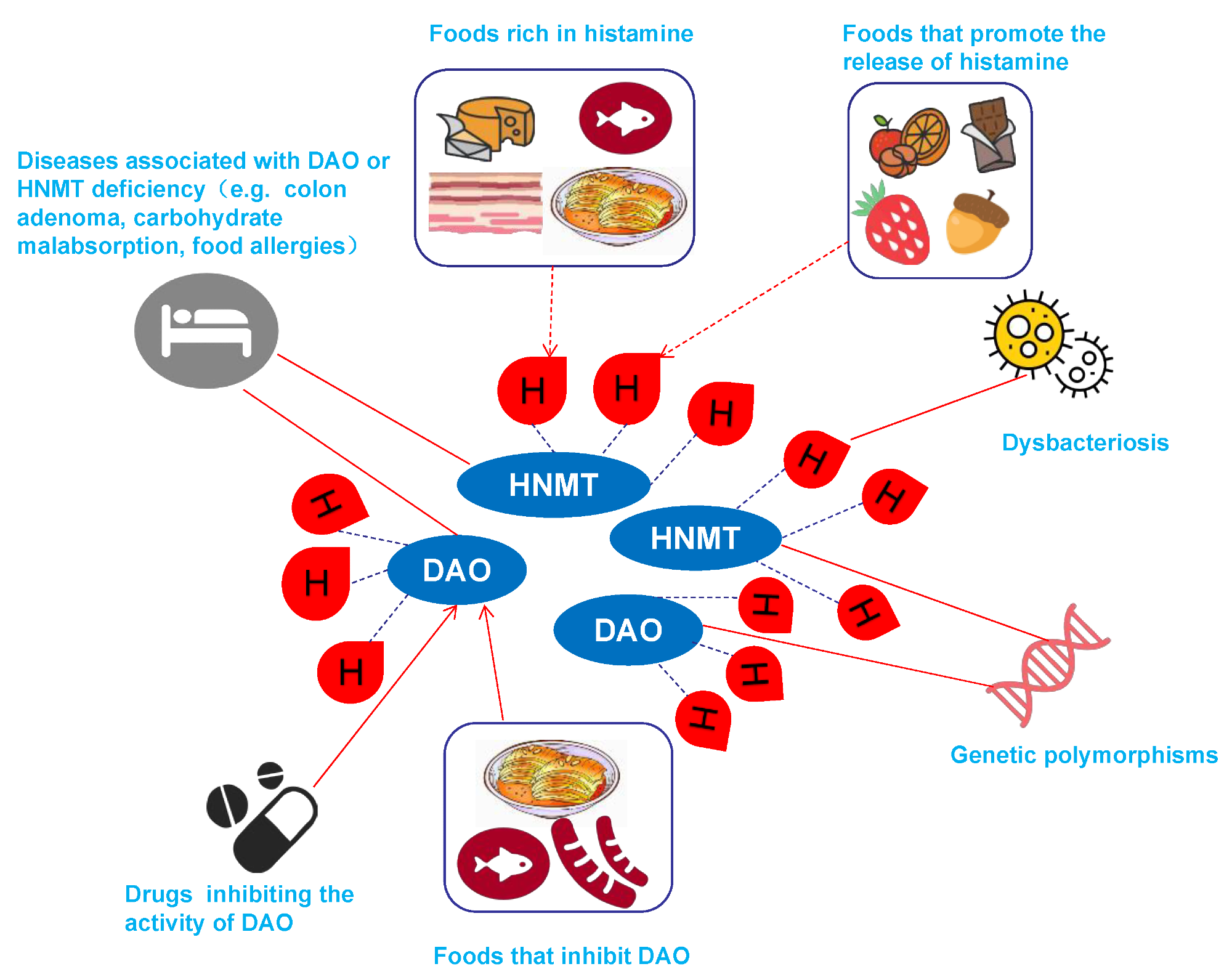

Intestinal DAO is the primary enzyme responsible for degrading dietary histamine. Reduced DAO activity can occur due to genetic defects, gastrointestinal disorders, or pharmacological inhibition by agents such as verapamil, clavulanic acid, chloroquine, or cimetidine.

By preventing its clearance, functional impairments in DAO or HNMT promote histamine accumulation in the body. Alcohol, particularly red wine, increases endogenous histamine release and competes with acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) to retard histamine metabolism, thereby raising histamine levels.3,5

Gut dysbiosis and barrier dysfunction facilitate histamine overproduction by bacteria, including Enterobacteriaceae species such as Morganella morganii and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Lactobacillus hilgardii, L. buchnerii, and L. curvatus, which are also found in fermented foods, produce histamine. Other biogenic amines such as putrescine and cadaverine may compete with DAO, further impairing histamine degradation.

The causes of HIT. The red drop with H represents the histamine. The etiology of HIT is primarily related to genetic polymorphisms of DAO or HNMT, diseases associated with DAO or HNMT deficiency, dysbacteriosis, drugs that inhibit DAO activity, foods rich in histamine, foods that inhibit DAO, and foods that promote histamine release.5

Reduced microbial diversity, alterations in key taxa, and increased intestinal permeability facilitate systemic histamine entry. Studies report increased abundance of Proteus and Bifidobacterium and lower counts of Butyricimonas and Hespellia among HIT patients.3,5

Mutations in the amine oxidase, copper-containing 1 (AOC1 or DAO), and HNMT genes can reduce enzyme expression or activity, thereby predisposing individuals to HIT. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) rs10156191, rs1049793, rs45558339, and rs35070995 are associated with reduced DAO function, which increases the risk of developing HIT.1,2

Symptoms and overlap with other conditions

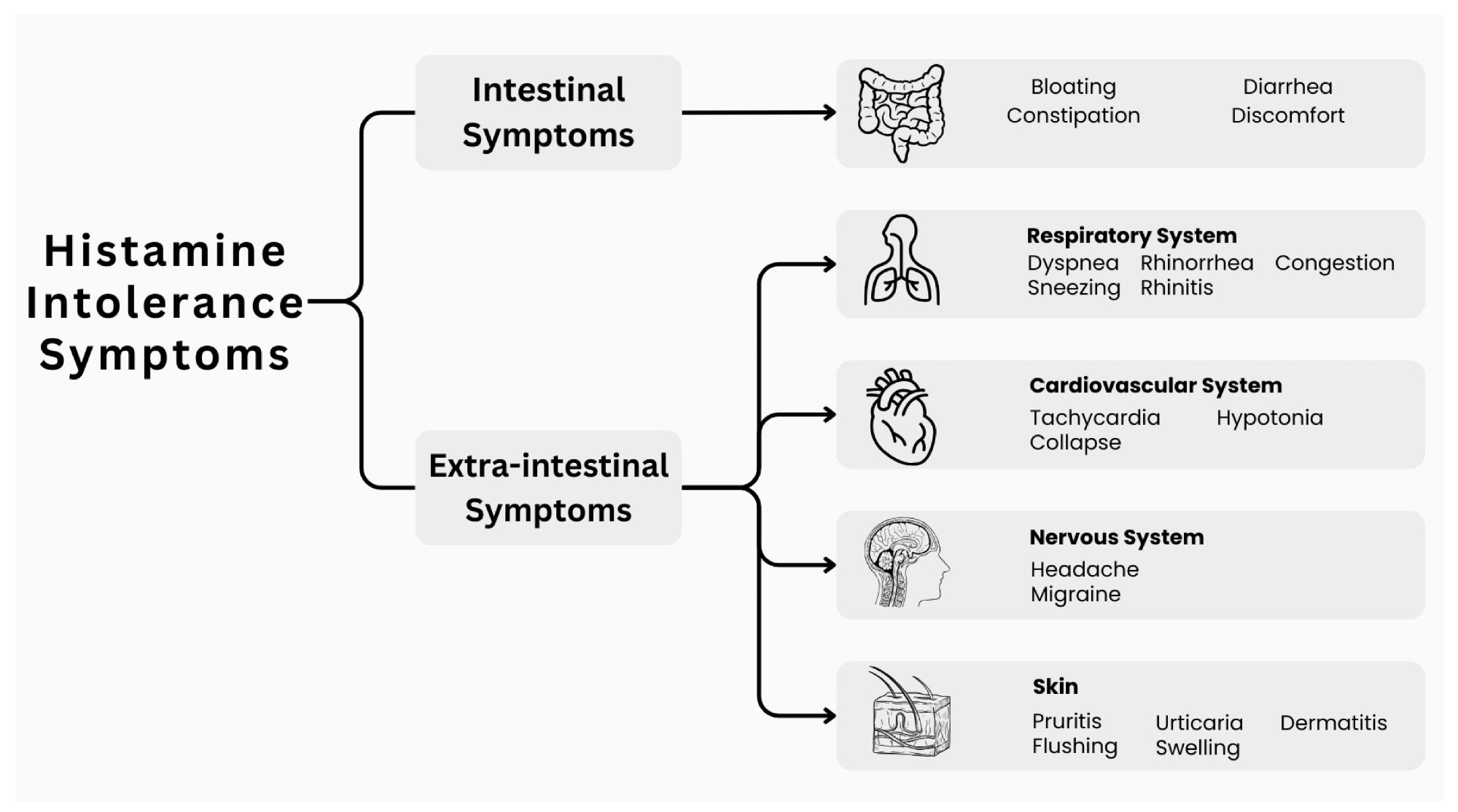

HIT presents with a wide range of vague symptoms due to activation of histamine receptors H1, H2, H3, and H4. H1 is primarily expressed in the nasal mucosa and lungs, whereas H2 is present in the gastric mucosa and the heart. H3 can be found in the central nervous system (CNS), while H4 is most often found in immune cells.

Symptoms associated with histamine intolerance.3

HIT patients experience gastrointestinal symptoms such as bloating, abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, and constipation. Respiratory symptoms may include nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, sneezing, and shortness of breath (dyspnea).

Dermatological features such as hives, pruritus, flushing, and swelling, neurological symptoms like headaches and migraines, as well as cardiovascular symptoms including tachycardia, hypotension, and collapse have also been reported.3

HIT symptoms frequently mirror those observed in food allergies, mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). Some of the different clinical features shared between these conditions include bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea or constipation, flushing, skin rashes, nasal congestion, and fatigue.5

The absence of standardized tests and wide variability in individual histamine tolerance complicate diagnosis. Common symptoms between HIT and gastrointestinal or allergic disorders lead to frequent misdiagnosis, thus emphasizing the urgent need for a universally accepted diagnostic framework for HIT.3

The surprising truth about histamine intolerance | Dr. Will Bulsiewicz

Current evidence and controversies

In a clinical context, gastrointestinal symptoms have been reported in over 90% of HIT patients, whereas multi-system involvement affected 97% of patients. Abdominal distension was the most common symptom at a prevalence of 92%, while postprandial fullness, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and constipation were reported in 55-73% of cases. Neurological and cardiovascular issues, such as dizziness, headaches, and palpitations, were also common, followed by respiratory and skin symptoms.7

Previously, DAO deficiency was reported in 80% of 31 adult patients experiencing various HIT symptoms, some of which included urticaria, pruritus, abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, vomiting, headache, rhinitis, and cough.8 Multiple studies have similarly reported an association between reduced DAO activity and the development of headaches, gastrointestinal symptoms, and dermatological symptoms.9,10

One case report described a 45-year-old woman with persistent laryngopharyngeal reflux whose throat clearing and cough improved after following a low-histamine diet.11 Similarly, a systematic review of 1,668 chronic urticaria patients reported limited benefit of systematic low-histamine diets (complete remission in ~12%) but better outcomes with individualized dietary exclusions, suggesting that dietary modification may help only a subset of patients.12

Provocation tests demonstrate that moderate doses of histamine can trigger HIT symptoms in susceptible individuals. However, in real-life situations, people consume meals that include other substances that influence histamine absorption and metabolism, thereby affecting histamine bioavailability.

DAO deficiency is frequently observed in HIT cohorts. Nevertheless, this condition also occurs in asymptomatic individuals, which prevents researchers from definitively determining DAO deficiency as a cause, a consequence, or a nonspecific biomarker of HIT.13

Prevalence estimates suggest that HIT may affect 3–6% of the population, with a higher incidence in women; however, these figures remain uncertain due to the lack of standardized criteria.

Diagnostic approaches and limitations

Following a low-histamine diet for four to eight weeks remains the primary diagnostic tool for HIT, with remission or improvement of at least two typical symptoms suggesting diagnosis. Food-symptom diaries or digital tracking apps can also be used to correlate intake with symptom onset.14

Serum DAO levels of 10 U/mL or less, measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or radioimmunoassay, have been proposed as a diagnostic threshold. However, serum DAO has poor reproducibility, fluctuates daily, and is not validated as a standalone diagnostic test.

Intestinal biopsy-based DAO assessment is more direct but invasive and non-standardized. Other methods, such as plasma histamine levels, the histamine 50-skin-prick test, and histamine provocation, are less reproducible, cannot differentiate HIT from allergies, and may lead to adverse reactions.

Fecal histamine testing is less reliable due to the contribution of microbial contaminants. Genetic testing for DAO-related SNPs may provide supportive but non-definitive evidence.1,2

Immunoglobulin E (IgE) testing for food allergies, serum tryptase analysis for mastocytosis, evaluation for intestinal diseases such as celiac disease and Crohn’s disease, and infections, as well as reviewing DAO-inhibiting medications, can also be used to diagnose HIT. After exclusion, a low-histamine diet trial, supplemented with laboratory measures, can begin.4,14

Management strategies

Reducing histamine intake involves eliminating aged cheeses, cured meats, fresh, canned, or fermented oily fish, fermented vegetables, citrus, strawberries, tomatoes, avocados, chocolate, nuts, wine, and beer from the diet. Comparatively, low-histamine foods that can be consumed in greater quantities include fresh meat and fish, eggs, rice, herbal teas, and most vegetables.

HIT symptoms often improve within two to four weeks after diet initiation, after which gradual reintroduction can help define tolerance. Boiling foods can also reduce their histamine levels, with up to 83% of histamine removed from spinach after boiling.2,15

Clinical evidence for low-histamine diets remains limited and heterogeneous. Some patients benefit substantially, while others show no improvement, suggesting that histamine intolerance is not the sole mechanism behind symptoms.

In clinical trials, oral DAO has been shown to improve gastrointestinal, skin, cardiovascular, and respiratory symptoms. In migraine patients, DAO supplementation can reduce attack duration and triptan use. However, the effectiveness of DAO supplementation is inconsistent, with some studies showing minimal or no benefit.

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) permits up to 0.9 mg/day of DAO for special medical purposes, with current studies investigating the efficacy of plant-based DAO sources. DAO supplements may allow liberalization in diet; however, any potential benefits diminish after discontinuation. Antihistamines (H1/H2 blockers) may provide short-term relief but can lower DAO activity, necessitating individualized and time-limited use.1,3,5

DAO deficiency may be due to intestinal inflammation, mucosal injury, or dysbiosis. Pathological conditions such as IBD, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, and carbohydrate malabsorption reduce DAO levels. Hormonal fluctuations (e.g., menstrual cycle) and micronutrient deficiencies in vitamin C, B6, copper, and zinc may further impair DAO activity.

Few gut bacteria produce histamine, while others, such as Lactiplantibacillus plantarum D-103, can degrade it, which has sparked increased interest in the development of probiotics capable of effectively targeting histamine degradation. Although promising, probiotic therapies remain experimental, with only preliminary human data.

Image Credit: Sdtozdmr / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Sdtozdmr / Shutterstock.com

Conclusion: Real condition or misdiagnosis?

Healthcare professionals increasingly recognize HIT as a plausible yet poorly defined clinical condition. Unspecific, overlapping symptoms and the absence of standardized diagnostic criteria complicate diagnosis.

Although dietary modification and DAO supplementation show therapeutic promise, small study populations and methodological variability limit the generalizability of these findings. Systematic reviews emphasize that the current evidence is of low quality, often uncontrolled, and does not yet establish causality between DAO deficiency and symptoms.

Thus, future studies are needed to identify robust biomarkers and establish precise definitions to improve diagnostic accuracy, prevent misdiagnosis, and reduce the impact on patients’ quality of life. At present, histamine intolerance should be considered a working hypothesis rather than a fully validated medical diagnosis.

Caution against self-diagnosis without medical guidance

Self-diagnosis of HIT and unsupervised dietary restriction may pose significant risks. These include masking other conditions, delaying appropriate medical evaluation, and causing unnecessary nutritional deficiencies. Because symptoms overlap with food allergy, IBS, celiac disease, mast cell disorders, infections, and medication effects, structured medical assessment and exclusion of alternative causes are essential before committing to restrictive diets. Diet trials should be time-limited, nutritionally supervised, and followed by a systematic reintroduction to minimize the risk of deficiency and confirm the true triggers.

References

- Comas-Basté, O., Sánchez-Pérez, S., Veciana-Nogués, M. T., et al. (2020). Histamine Intolerance: The Current State of the Art. Biomolecules 10(8), 1181. DOI:10.3390/biom10081181, https://www.mdpi.com/2218-273X/10/8/1181

- Hrubisko, M., Danis, R., Huorka, M., & Wawruch, M. (2021). Histamine Intolerance—The More We Know, the Less We Know. A Review. Nutrients 13(7), 2228. DOI:10.3390/nu13072228, https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/13/7/2228.

- Jochum, C. (2024). Histamine Intolerance: Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Beyond. Nutrients 16(8); 1219. DOI:10.3390/nu16081219, https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/16/8/1219.

- E. Kovacova-Hanuskova, T. Buday, S. Gavliakova, & J. Plevkova. (2015). Histamine, histamine intoxication, and intolerance. Allergolgia et Immunopathologia 43(5):498-506. DOI:10.1016/j.aller.2015.05.001, https://www.elsevier.es/en-revista-allergologia-et-immunopathologia-105-pdf-S0301054615000932.

- Zhao, Y., Zhang, X., Jin, H., et al. (2022). Histamine Intolerance—A Kind of Pseudoallergic Reaction. Biomolecules, 12(3), 454. DOI:10.3390/biom12030454, https://www.mdpi.com/2218-273X/12/3/454.

- Frei, R., Ferstl, R., Konieczna, P., et al. (2013). Histamine receptor 2 modifies dendritic cell responses to microbial ligands. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 132; 194-204. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.013, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0091674913000912.

- Schnedl W. J., Lackner S., Enko D., et al. (2019). Evaluation of symptoms and symptom combinations in histamine intolerance. Intestinal Research 17;427-433. DOI:10.5217/ir.2018.00152, https://www.irjournal.org/journal/view.php?doi=10.5217/ir.2018.00152.

- Mušič E., Korošec P., Šilar M., et al. (2013). Serum diamine oxidase activity as a diagnostic test for histamine intolerance. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 125:239-243. DOI:10.1007/s00508-013-0354-y, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00508-013-0354-y.

- Pinzer T. C., Tietz E., Waldmann E., et al. (2018). Circadian profiling reveals higher histamine plasma levels and lower diamine oxidase serum activities in 24% of patients with suspected histamine intolerance compared to food allergy and controls. Allergy 73(4):949-957. DOI:10.1111/all.13361, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/all.13361.

- Izquierdo-Casas, J., Comas-Baste, O., Latorre-Moratala, M. L., et al. (2018). Low serum diamine oxidase (DAO) activity levels in patients with migraine. Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry 74(1):93-99. DOI:10.1007/s13105-017-0571-3, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13105-017-0571-3.

- Alnouri, G., Cha, N., & Sataloff, R. T. (2022). Histamine Sensitivity: An Uncommon Recognized Cause of Living Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Symptoms and Signs - A Case Report. Ear, Nose & Throat Journal. DOI:10.1177/0145561320951071, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0145561320951071.

- Cornillier, H., Giraudeau, B., Samimi, M., et al. (2019). Effect of diet in chronic spontaneous urticaria: A systematic review. Acta Derm. Venereol., 99:127-132. DOI:10.2340/00015555-3015, https://medicaljournalssweden.se/actadv/article/view/3091.

- Wöhrl S., Hemmer W., Focke M., et al. (2004). Histamine intolerance-like symptoms in healthy volunteers after oral provocation with liquid histamine. Allergy Asthma Proc., 25(5):305–311. DOI:10.2500/1088541042167459, https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/ocean/aap/2004/00000025/00000005/art00006;jsessionid=5d0b22mf8ova5.x-ic-live-01.

- Tuck, C. J., Biesiekierski, J. R., Schmid-Grendelmeier, P., & Pohl, D. (2019). Food intolerances. Nutrients 11(7); 1684. DOI:10.3390/nu11071684, https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/7/1684.

- Sánchez-Pérez, S., Comas-Basté, O., Rabell-González, J., et al. (2018). Biogenic amines in plant-origin foods: Are they frequently underestimated in low-histamine diets? Foods 7(12); 205. DOI:10.3390/foods7120205, https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/7/12/205.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Aug 27, 2025