Professor Strachan first proposed the hygiene hypothesis back in 1989. Reviewing the evidence, he suggested that one of the causes of the recent rapid rise in allergic diseases in children was lack of exposure to childhood infections.

In conjunction, he suggested that this has occurred because of smaller families which means less spread of infections, and “improved household amenities and higher standards of personal cleanliness”

From that, the notion has arisen that we have become “too clean for our own good”. This has since been widely publicized through the media and has become part of our culture. What we now realize is that although the basic idea of need for contact with microbes was right, it is not contact with infectious micro-organisms that is important.

If we take the literal meaning of the word “hygiene,” as the things we do to protect us from infectious disease, it also follows that hygiene is unlikely to have caused the loss of exposure to the microbes that we do need.

Research is now showing that the hygiene hypothesis – the idea that allergies are the price we are having to pay for our “modern obsession with cleanliness” is a misleading and dangerous misnomer which is both undermining our attitudes to hygiene and hindering the search for ways to reverse the trends in allergies and other inflammatory diseases.

Particularly worrying for public health is that this is happening at a time when hygiene is becoming more rather than less important. Having enjoyed the benefits afforded by sanitation, clean water and food, antibiotics and vaccines over the last 2 centuries, we face the possibility that antibiotic resistance may rob us of the ability to treat infection.

The need for better hygiene is also being driven by increasing numbers of vulnerable groups at increased risk of infection living in the community, and increasing amounts of healthcare being delivered in out-of-hospital settings.

Agencies worldwide, developing strategies for dealing with emerging infections such as influenza, SARS and Ebola, now recognize hygiene as the first line of defense during the early critical period before mass measures such as vaccination become available.

How does the ‘Old Friends’ mechanism differ from the hygiene hypothesis?

The Old Friends mechanism was first proposed by Professor Graham Rook in 2003. He said that the microbial exposures that we need are not infectious diseases because they evolved in human communities much too late.

The organisms vital to the development of our immune system are what he calls our ‘old friends’, the microbes that we were in contact with during early hunter-gatherer times when our immune systems were developing.

During human development, the immune system evolved primarily to protect us from infectious diseases. As soon as a pathogen enters the body and starts to produce adverse reactions, the body’s immune system responds, first with a general immune response and then by producing specific antibodies against the infecting organism.

Whilst the primary function of the human immune system is to protection against harmful pathogens, equally important this system must learn to tolerate the non-harmful agents which we also constantly encounter in our daily lives - i.e. we also had to evolve immunotolerance to things that weren't going to harm us.

Rook proposed that the old friends microbes, are the largely non-harmful organisms (or organisms which we had to learn to tolerate such as worms) that inhabit our natural environment, animals and the other humans that we live with.

What Rook proposed is that the Old Friends microbes evolved an essential role in teaching the immune system not only which microbe species are harmless and need to be tolerated rather than attacked, but also to tolerate harmless agents such as pollen, food allergens and our body tissues.

If the immune system becomes dysregulated or imbalanced due to lack of interaction with Old Friends, it can start to attack these agents causing allergic reactions such as hay fever, asthma eczema and food allergies.

We now realize that this mechanism is also involved in other chronic diseases. For example, immune dysregulation can also cause the immune system to attack our own body tissues causing diseases such as multiple sclerosis and type 1 diabetes.

Why have we lost contact with the “Old Friends” microbes?

Time has shown that there's probably no one single cause; it's the combined result of a whole range of public health, lifestyle and medical changes that have occurred over the last two hundred years.

The most obvious are things like clean water and sanitation and cleaner food, which we've developed to protect us from infectious diseases. Although these changes have been vital to protecting us against infectious disease, they have also deprived us of exposure to Old Friends microbes which tend to occupy the same habitats.

On top of that, it has become apparent that old friends exposure is particularly important in early life, both prenatally, immediately after birth and on through into early childhood.

We have been losing contact with the old friends that we would normally get at these times through things such as caesarean section and lack of breastfeeding. Less time spent outdoors in green spaces means that children are also getting less exposure to environmental microbes.

It's not just about contact with Old Friends microbes. Many of these species take up residence on our skin surface and within our gut, respiratory tract and so on to build our microbiome, the millions of organisms which have a permanent home in our body.

Building and sustaining a diverse microbiome is important for a number of aspects of our health in addition to its interaction with the immune system to sustain immune tolerance to things like allergens.

We now know that overprescribing of antibiotics in early childhood can have a detrimental effect on the gut microbiome There is now good evidence that children who have excessive antibiotics prescriptions in early childhood are more prone to asthma and allergies.

Diet is another factor. We believe that the diet can very much affect the way in which the microbiome builds and is sustained. The wrong sort of diet can mean the wrong sort of microbiome and, again, this can affect the balance of our immune system and lead to increased risk of allergies and other inflammatory diseases.

How much evidence is there that domestic hygiene and cleanliness is responsible for the loss of vital microbial exposures?

Very little. If our day to day hygiene (the things we do to protect ourselves from infection) and cleanliness (keeping our homes free from visible dirt) habits contribute, their role is likely to be small relative to other factors.

Our modern homes are “teeming with microbes” which originate from the people and domestic animals living there, the food they eat, together with input from the local outdoor environment.

The idea that we could create “sterile” homes through excessive cleanliness is implausible; as fast as microbes are removed, they are replaced, via dust and air from the outdoor environment, and microbes shed from the human body and our pets, and contaminated foods brought into the homes.

If the microbial content of modern urban homes hasn’t been altered by home and personal cleanliness, what has happened in our homes and everyday lives which has caused us to interact with a different and less diverse mix of microbes?

The key point may be that the microbial content of modern urban homes has altered, not because of home and personal cleanliness, but because, prior to the 1800s, people lived in predominantly rural surroundings, had very different diets and no access to antibiotics.

As a result we now interact with an altogether different and less diverse mix of microbes - the microbes that used to be there just aren't there anymore.

For example, the microbiome of our own bodies has changed, so the microbes we shed into our home environment are different. In the same way, most of us live in an urban home surrounded by a concrete jungle which means that the microbes we previously used to live with and need from our rural environments just aren't getting into our homes.

The fact is that they're just not there – or not there in the same abundance, so it doesn't matter how clean or how hygienic we are in terms of our daily lives, they're just not there.

Could strategies which help us restore interaction with our old friends help to reverse the trends in allergic diseases?

Although there is mounting evidence that a range of lifestyle changes have reduced or altered exposure to vital microbes, at present we have little or no data indicating whether or to what extent strategies, such as encouraging natural childbirth, breast feeding, increased social exposure through sport and other outdoor activities, less time spent indoors, diet and appropriate antibiotic use might help to restore the microbiome and reduce risks of allergic disease.

Much further work is needed to understand what is happening, and most importantly to measure the impact of lifestyle changes on allergy rates in human populations

First of all, we don't know whether some microbial species are more important than other and if so which ones – or whether it is diversity of microbe exposures which is the key

We don't know what times of life are important. We know that early childhood is very important, but we don't know the extent to which those exposures need to be sustained as we go on into adulthood.

We certainly don't know whether or to what extent, once we've developed these inflammatory diseases, restoring that microbial exposure could reverse those diseases.

How can we protect ourselves against harmful microbes whilst at the same time restoring contact with our old friends?

Although we still have a long way to go before we can use our new knowledge to tackle the rise in allergies, the fact that allergies are not the price we have to pay for protection against infectious diseases is good news for hygiene.

But, if we are to maximize protection against infection whilst at the same time sustaining exposure to “Old Friends” microbes, we need smarter approaches to hygiene than the “scrupulous cleanliness” approach advocated by Florence Nightingale. We need to understand that hygiene is something more than “keeping our home spotlessly clean”.

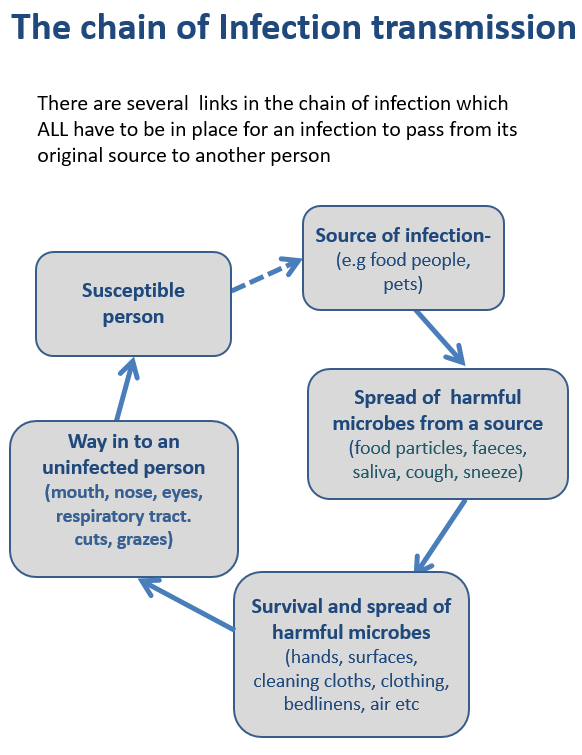

What we believe is that smarter hygiene is “targeted hygiene”. This starts from understanding where the harmful microbes are coming from and how they're being spread – what we call the “chain of infection”.

Looking at the home, harmful microbes mostly enter our home via people, the animals we live with, and the food that we handle, particularly raw foods.

Targeted hygiene is also based on understanding the key routes (via hands, hand contact surfaces, food contact surfaces and cleaning cloths etc.) by which harmful organism are transmitted around the home and other environments, and targeting hygiene practices in these places and at the times that matter, most particularly those associated with activities such as preparing food, coughs and sneezes, going to the toilet, doing the laundry etc. The aim is to break the chain of infection and prevent us from being exposed to these organisms.

It’s important to understand that hygiene is not about the state of our homes and how clean it is. It’s about the habits we adopt, what we do during our daily life activities to reduce the risk of spread of infection

How important is microbiome science going to be in the future of healthcare?

Hugely important because what we are now seeing is that the microbiome is important to all sorts of aspects of our health. It’s not just important for immune function; it's also important for our digestive and other aspects of our health.

Microbiome science shows us that our microbiome constitutes an organ, as essential to health, as our liver and kidneys. The microbiome is an essential part of healthy living.

In short, we're just going to have to view our microbial world very differently in the future. We've learned to live with our animal world and know that some of them are beneficial to us, while others such as lions, tigers and poisonous snakes are a danger to us.

We need to recognize that microbes are just another part of the animal world and are vital to our health - but at the same time we must respect that some species are harmful to us.

What needs to be done to change public health and professional perceptions around hygiene?

We've got to view our microbial world very differently and, like our animal and plant world, see it as something we are part of rather than something alien.

It's largely about changing our perceptions about microbes and what they are. As children we are brought up seeing pictures of germs as being horrid, slimy, green creatures and things that make us think ”yuk.”

The media will pick up a story for example and say there are millions of germs on our toilet seats or on a chopping board, for example, when, in fact, what has been found are millions of microbes, a proportion of which are our old friends.

The dictionary definition of 'germs' is "Pertaining to small organisms, most particularly those which are harmful to us." We've got to stop using this term 'germs' to instill fear.

The other thing I think we also need to understand is that that there is a difference between cleanliness and hygiene.

Cleanliness is a state that I think we're hardwired to seek after. It's part of building a feeling of well-being which in turn contributes to our health. Although cleanliness contributes to hygiene, (protection against infection) it's not hygiene in itself.

We think we'll keep our homes clean; we'll keep our homes hygienic. Hygiene is not a state, hygiene is something more than just cleanliness, it's about what we do at the times that matter to prevent the spread of germs and become infected.

I think a lot of education is needed and it's not just about restoring confidence in hygiene, which is vital part of containing the burden of infectious disease.

We now know that failure to build a diverse microbiome may be associated with rising levels of allergic diseases, autoimmune disease, type 1 diabetes and inflammatory bowel disease. It may also contribute to cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorders, depression and reduced stress resilience.

We will not be able to tackle these issues, whilst we remain wedded to the original concept of the hygiene hypothesis; that children have more infections and that children living in homes that are too clean are more likely to get allergies.

Changing perceptions of the public, the media and public health experts represents a real challenge – but it’s time we recognised that using home and personal cleanliness as a scapegoat for a problem which has a much more complicated set of causes is not only unjustified but is also diverting effort and attention from finding the true causes and workable solutions

Where can readers find more information?

- http://www.ifh-homehygiene.org/books/simple-guide-healthy-living-germy-world

- Bloomfield SF, Rook GAW, Scott EA, Shanahan F, Stanwell-Smith R, Turner P. Time to abandon the hygiene hypothesis: New perspectives on allergic disease, the human microbiome, infectious disease prevention and the role of targeted hygiene. Perspectives in Public Health 2016; 136(4): 213–224.

- Bloomfield SF In Future we are going to have to view our microbial world very differently Perspectives in Public Health 2016; 136(4): 183-184.

About Professor Sally Bloomfield

Sally Bloomfield is currently Chairman of the International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene (IFH, www.ifh-homehygiene.org). She is also an Honorary Professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Her work is devoted to raising awareness of the importance of hygiene in preventing the transmission of infectious disease in home and everyday life settings, and developing and promoting hygiene practice based on sound scientific principles.

She is also working to develop understanding of “hygiene issues” such as the “hygiene hypothesis” and “antimicrobial resistance”.

Sally was previously a Senior Lecturer at Kings College London from 1972 to 1997, She now works as a consultant in infectious disease prevention. She has published over 100 papers on the subject of infection prevention, hygiene and the action of antimicrobial agents.