Introduction

What is Kava?

Clinical Applications: Evidence-Based Benefits

Safety and Toxicology: The Liver Toxicity Controversy

Regulatory Status and Public Health Perspective

Guidelines for Safe Use

Conclusions

References

Further Reading

Kava, a traditional Pacific Island beverage, is increasingly recognized in Western wellness circles for its anxiolytic and calming properties, supported by clinical research. However, concerns regarding liver toxicity highlight the need for safe preparation, standardized regulation, and informed consumer use.

Kava, also known as kava kava (Piper methysticum; from Latin 'pepper' and Latinized Greek 'intoxicating'), is a member of the pepper family indigenous to the Pacific Islands. The term 'kava' originates from the Tongan and Marquesan languages, meaning 'bitter.' Kava refers both to the plant itself and to the psychoactive beverage traditionally prepared from its root.. Image Credit: Andika Purnama / Shutterstock.com

Kava, also known as kava kava (Piper methysticum; from Latin 'pepper' and Latinized Greek 'intoxicating'), is a member of the pepper family indigenous to the Pacific Islands. The term 'kava' originates from the Tongan and Marquesan languages, meaning 'bitter.' Kava refers both to the plant itself and to the psychoactive beverage traditionally prepared from its root.. Image Credit: Andika Purnama / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Kava is becoming increasingly popular in Western wellness circles as a natural remedy for stress, anxiety, and insomnia. This rising interest has renewed focus on its cultural origins in the South Pacific, where it has been used for centuries in ceremonial and healing practices.

Although widely valued for its calming effects, kava has also raised concerns regarding safety, particularly in relation to liver health. As its popularity grows, there is an urgent need to examine the scientific evidence, regulatory landscape, and guidelines for safe and informed use.1

What is Kava?

Kava, botanically known as Piper methysticum, is a perennial shrub native to the Pacific Islands, particularly in regions such as Vanuatu, Fiji, and Tonga. Kava belongs to the pepper family and has been consumed for centuries in ceremonial and social contexts throughout Oceanic regions. Traditional kava preparations involve grinding the plant’s roots, which are its most pharmacologically active part, into a powder. This powder is then mixed with water or coconut milk to form a cloudy beverage.1,2

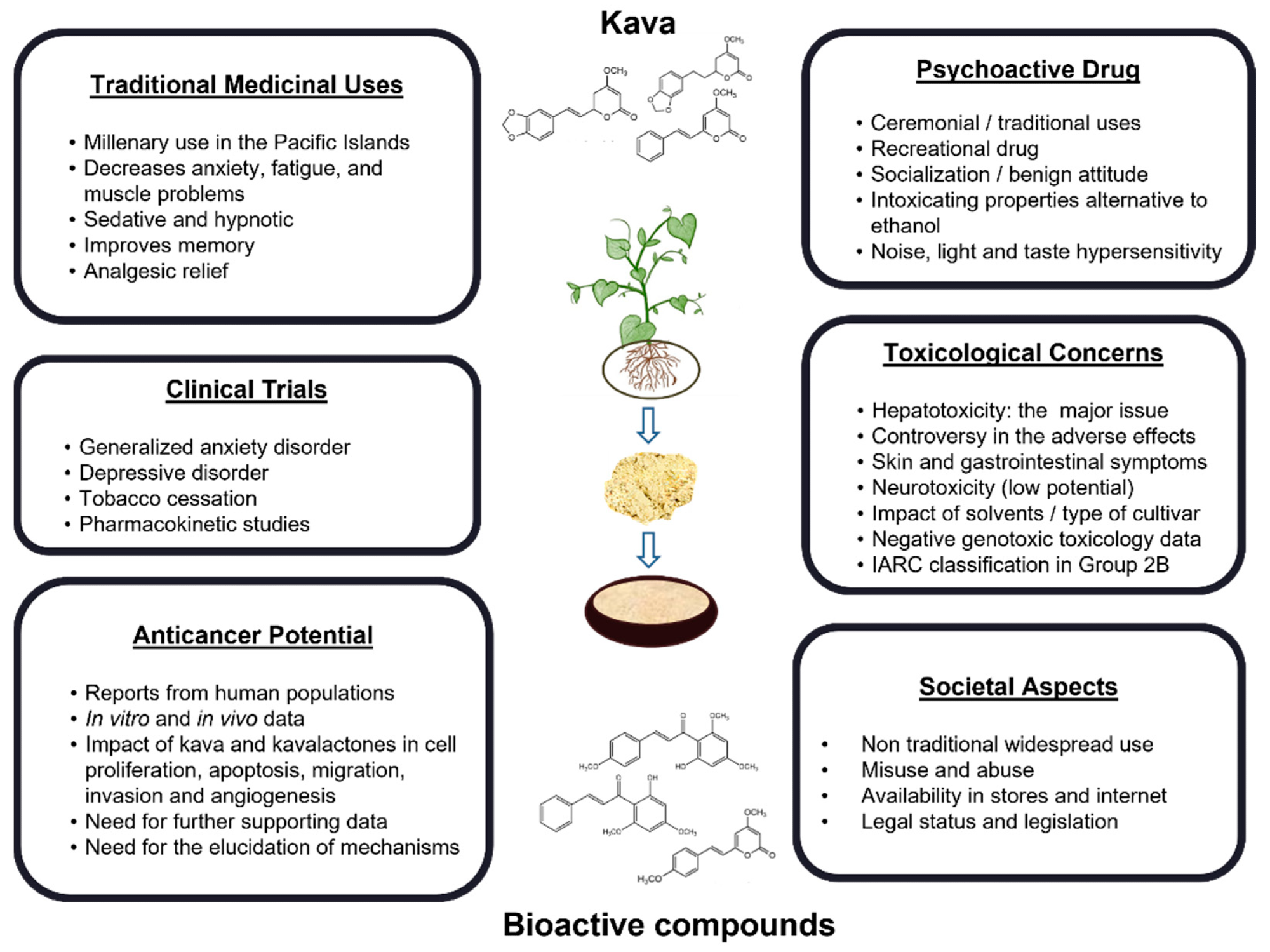

Different contexts in which kava can be studied.2

Different contexts in which kava can be studied.2

The active ingredients in kava are a unique group of lipophilic compounds called kavalactones, which are nearly exclusive to this plant. These compounds are credited with kava’s psychoactive properties, particularly its calming, anxiolytic, and muscle-relaxing effects.

Among the 19 identified kavalactones, six account for the majority of their pharmacological action, including kavain, dihydrokavain, methysticin, dihydromethysticin, yangonin, and desmethoxyyangonin. These compounds primarily act by modulating gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) pathways in the brain.1,2

Kava is consumed as a traditional drink, as well as in tablet or capsule form as a herbal anxiolytic. Importantly, the type of cultivar, plant part used, and method of extraction can influence its chemical composition and safety profile.1,2

Image Credit: ChameleonsEye / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: ChameleonsEye / Shutterstock.com

Clinical Applications: Evidence-Based Benefits

Peer-reviewed studies suggest that kava, particularly its active components like kavalactones, provides significant anxiolytic benefits, especially for mild to moderate anxiety. Multiple double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have reported that standardized kava extracts effectively reduce anxiety symptoms, often with results comparable to those achieved using benzodiazepines, but with fewer adverse effects. These benefits have also been observed in individuals experiencing anxiety related to menopause and medical procedures.2,3

Pharmacologically, kava produces calming effects by modulating GABA type A receptors. Kava also enhances ligand binding and increases receptor availability, particularly in limbic brain regions such as the amygdala and hippocampus, which are associated with emotion and stress regulation. This GABAergic activity is similar to that of benzodiazepines but does not impair cognitive function.

Kava has also been shown to inhibit voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels, which reduces excessive neuronal firing, as well as prevent the reuptake of norepinephrine, which contributes to mood stabilization. Kava also promotes better sleep quality and reduces stress-induced restlessness, thus making it a versatile option for managing anxiety-related conditions.2,3

Safety and Toxicology: The Liver Toxicity Controversy

The safety of kava has been widely debated due to reports linking its use to liver toxicity, including acute liver failure. Regulatory authorities in countries such as Germany, the United Kingdom, Canada, and parts of Europe have enacted bans or restrictions following over 90 reported cases of hepatotoxicity, with some resulting in liver transplants or death.

Despite these actions, investigations conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) and Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) have noted that many of these cases lacked complete data and that causality was often unconfirmed. Most serious reactions were linked to acetonic and ethanolic extracts, which differ chemically from traditional water-based preparations. Other factors that may have increased the toxicity of kava include the use of aerial plant parts, poor-quality cultivars, high doses, and interactions with other hepatotoxic drugs or alcohol.2,3,4

Traditional water-based kava, which has been primarily used in Pacific Island cultures, has not been associated with liver injury in epidemiological studies. WHO and TGA reviews emphasize that, when properly prepared from peeled roots of noble cultivars and consumed in moderation, kava is likely safe.

Both WHO and TGA recommended avoiding products made with organic solvents and highlighted the need for standardization, post-marketing surveillance, and pharmacogenetic research to further clarify the risks.3,4

Regulatory Status and Public Health Perspective

The regulatory status of kava varies significantly across regions, reflecting diverse views on its safety and public health implications. In the United States, kava is legally available as a dietary supplement, although the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued consumer warnings about potential liver toxicity.

The European Union previously imposed a ban on kaca following reports of hepatotoxicity; however, some countries have since partially reversed this decision. Australia and New Zealand permit regulated access to kava with specific rules on dosage, preparation, and labeling.4,5

The WHO recognizes the traditional use of kava in Pacific Island cultures and has called for stricter quality control measures, standardized preparation techniques, and more safety research. This has created friction between supporters of traditional medicine, who highlight centuries of ceremonial use, and regulatory agencies that rely on clinical safety data.4,5

Within the supplement industry, inconsistent product labeling and a lack of standardization have led to consumer confusion. Many products fail to clearly state the kava variety, extraction method, or concentration of kavalactones, all of which are crucial for determining safety and effectiveness. As interest in natural anxiety remedies increases, better regulation and consumer education are crucial to support safe and culturally respectful use.4,5

How the Kava Plant Produces Its Pain-Relieving and Anti-Anxiety Molecules

Guidelines for Safe Use

The safe use of kava depends on proper dosage, preparation, and the quality of the product. For standardized extracts such as WS 1490, a pharmaceutical-grade ethanolic extract of Piper methysticum standardized to 70 percent kavalactones, clinical studies support daily doses of up to 300 milligrams of kavalactones. Traditional water-based preparations made from the peeled root or rhizome generally contain lower concentrations and are considered safer than those extracted with acetone or ethanol.5

Long-term users should avoid combining kava with alcohol or other liver-affecting substances. Regular monitoring of liver enzymes is recommended for prolonged use, especially with non-traditional extracts.

Consumers are advised to purchase products made from noble cultivars using only the peeled root or rhizome. Stem peelings and aerial parts may contain toxic alkaloids like pipermethystine. High-quality products are solvent-free and confirmed through third-party testing for purity and kavalactone content.5

The WHO advises that pharmaceutical-grade kava should be available only by prescription and include warnings about potential interactions with medications such as anxiolytics, antipsychotics, and anticoagulants. Choosing reputable, water-based preparations and adhering to safety recommendations helps minimize health risks while preserving kava’s therapeutic potential for stress and anxiety relief.5

Mixed ethnicity kava users seated on fala/ibe (woven mats) and engaging in talanoa in Tāmaki Makaurau, Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand. Reproduced with permission from photographer: Todd M. Henry, 2022.7

Mixed ethnicity kava users seated on fala/ibe (woven mats) and engaging in talanoa in Tāmaki Makaurau, Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand. Reproduced with permission from photographer: Todd M. Henry, 2022.7

Conclusions

Kava presents a promising and culturally significant option for managing anxiety and promoting relaxation, with roots in centuries-old Pacific Island traditions and growing clinical support for its anxiolytic effects. However, the safety profile of kava depends heavily on preparation methods, plant quality, and dosage.

Regulatory oversight remains inconsistent across regions, underscoring the critical need for standardized guidelines, clear labeling, and effective consumer education. Continued clinical trials and pharmacogenetic research are critical to fully understand kava’s benefits and risks.

References

- Bian, T., Corral, P., Wang, Y., Botello, J., Kingston, R., Daniels, T., Salloum, R.G., Johnston, E., Huo, Z., Lu, J. and Liu, A.C. (2020). Kava as a clinical nutrient: promises and challenges. Nutrients, 12(10), 3044. DOI: 10.3390/nu12103044, https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/12/10/3044

- Soares, R. B., Dinis-Oliveira, R. J., & Oliveira, N. G. (2022). An updated review on the psychoactive, toxic and anticancer properties of kava. Journal of clinical medicine, 11(14), 4039. DOI:10.3390/jcm11144039, https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/11/14/4039

- Singh, Y. N., & Singh, N. N. (2002). Therapeutic potential of kava in the treatment of anxiety disorders. CNS drugs, 16, 731-743. DOI:10.2165/00023210-200216110-00002, https://link.springer.com/article/10.2165/00023210-200216110-00002

- World Health Organization. (2007). Assessment of the risk of hepatotoxicity with kava products. WHO Regional Office Europe. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43630/9789241595261_eng.pdf

- Richardson, W. N., & Henderson, L. (2007). The safety of kava–a regulatory perspective. British journal of clinical pharmacology, 64(4), 418. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02933.x, https://bpspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02933.x

- Aporosa, S. A., Itoga, D., Ioane, J., Prosser, J., Vaka, S., Grout, E., Atkins, M. J., Head, M. A., Baker, J. D., Blue, T., Sanday, D. H., Owen, M. W., Murray, C., Sivanathan, K., Cuthers, T., McCarthy, M., Bunn, J., Waqainabete, I., & Turner, H. (2025). Innovating through tradition: Kava-talanoa as a culturally aligned medico-behavioral therapeutic approach to amelioration of PTSD symptoms. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1460731. DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1460731, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1460731/full

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jul 1, 2025