Introduction

Definition and Basics

Common Reasons for Compounding

Types of Compounded Medications

Regulation and Oversight

Benefits and Controversies

The Future of Compounding

Conclusion

References

Discover how compounding pharmacies are transforming healthcare by creating tailor-made medications for patients with unique needs, offering critical alternatives when standard drugs fall short, and driving the next frontier in personalized medicine.

Image Credit: Mai.Chayakorn / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Imagine a patient with a life-threatening allergy to a dye commonly used in commercial medications. Despite the availability of effective drugs, they face dangerous reactions simply due to a non-active ingredient. Or consider a child who cannot swallow pills, yet requires medication only available in tablet form.

In these cases, compounded medication becomes vital when a standardized, mass-produced drug falls short.

Compounded medications are formulations created to meet individual patient needs when commercial drugs are unsuitable, unavailable, or intolerable. These custom-made drugs exemplify personalized medicine in practice, offering solutions that standard medications often cannot provide. Whether modifying dosage forms, excluding allergens, or combining multiple therapies into one, compounding enables clinicians to fine-tune treatments for unique patient profiles.1

Although representing a small percentage of prescriptions, compounded drugs play an essential role in ensuring personalized and accessible care. This article explores what compounded medications are, why they matter in modern healthcare, and how their benefits and risks shape regulatory and clinical decisions.

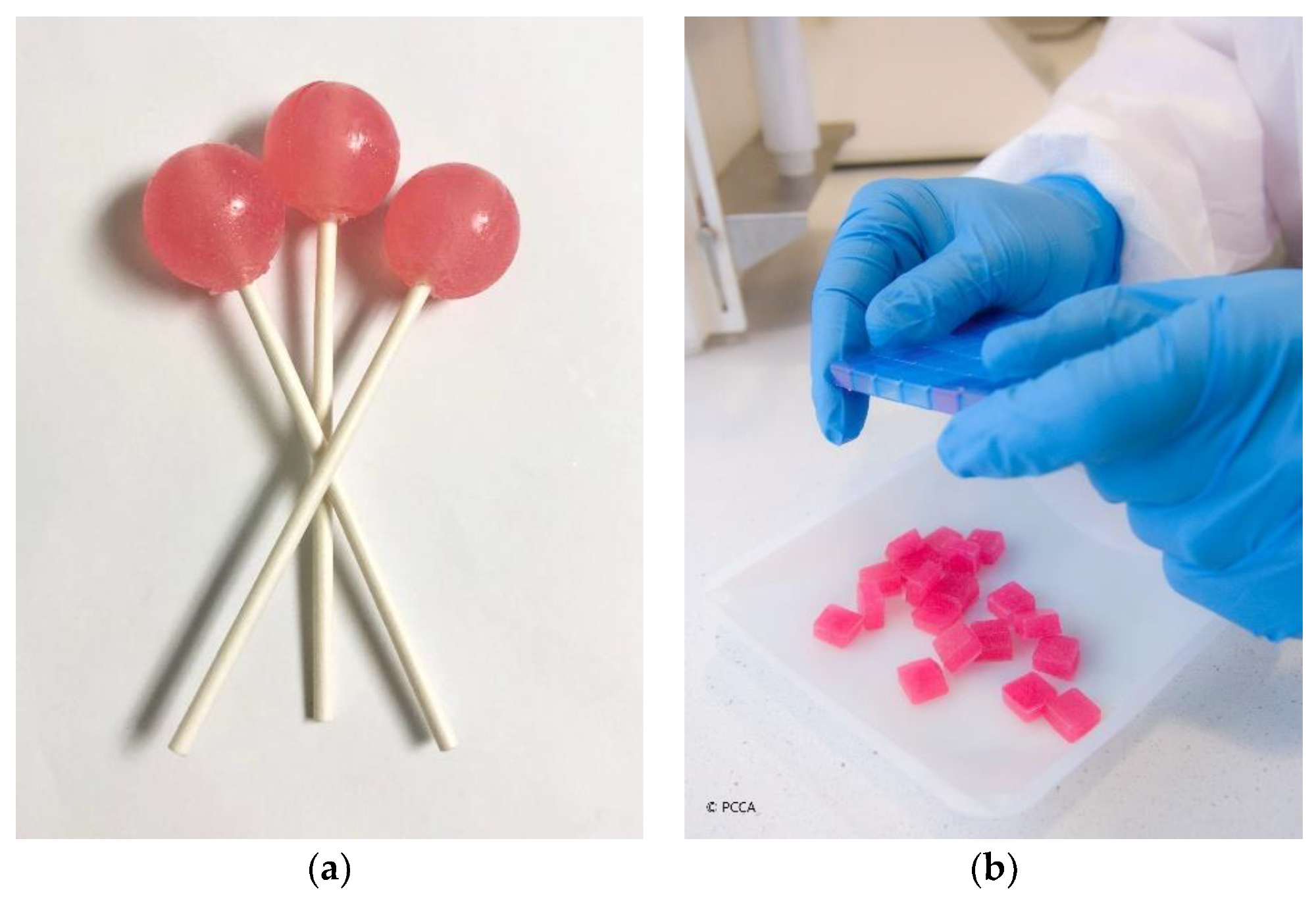

Child-friendly dosage forms: (a) medicated lollipops; (b) medicated lozenges (troches) (courtesy of PCCA, 2021).1

Definition and Basics

Pharmaceutical compounding is the customized preparation of medications by combining, mixing, or altering ingredients to accommodate the specific needs of a patient. Unlike commercially manufactured drugs approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), compounded medications are not standardized products. Instead, these formulations are made by licensed pharmacists or physicians in compounding pharmacies, typically based on a prescription for an individual.2

Compounding provides therapeutic solutions for patients who cannot use mass-produced medications due to allergies, dosage requirements, or drug unavailability.3 Compounding also enables healthcare providers to adapt drug formulations to unique clinical circumstances, such as combining active ingredients into a single dosage form or modifying the route of administration.

This customization is particularly valuable for managing chronic conditions, treating rare diseases, or addressing the needs of vulnerable populations like pediatric and geriatric patients.4

Common Reasons for Compounding

Allergies or Sensitivities

Some individuals are allergic to dyes, preservatives, or fillers that are often present in commercial drugs. Compounding allows for formulations to be free from these excipients.3

For example, a patient with a severe reaction to a preservative commonly used in oral suspensions may require a specially compounded version of the same drug without the preservative that causes an adverse reaction.

Discontinued or Unavailable Drugs

When a commercially manufactured drug is backordered or discontinued, compounding can be utilized. This is especially critical in cases where no alternative treatment exists, such as a discontinued thyroid medication with specific dosages not available in commercial products.1

Pediatric or Geriatric Needs

Children and older adults often require dose adjustments or alternative dosage forms such as liquids or lozenges, which may not be available commercially. For example, a child who cannot swallow tablets may be given a flavored liquid formulation to ensure accurate dosing and adherence.1

Alternative Dosage Forms

Transforming a pill into a topical cream, liquid, or suppository to accommodate the patient’s needs is a frequent reason for compounding. A patient with severe nausea who cannot retain oral medication might benefit from an injectable or suppository version of their prescribed drug.2

Palatability Improvements

Adding flavor to medications can enhance adherence, particularly among pediatric patients. A bitter-tasting antibiotic, for example, can be compounded into a palatable, fruit-flavored liquid to improve acceptance and ensure that the child completes the antibiotic course. 1

Types of Compounded Medications

Custom-compounded bioidentical hormones are frequently prescribed to manage menopausal symptoms, particularly when patients require specific dosage forms or combinations not available in FDA-approved products.2 Pain management creams may also contain multiple active ingredients such as ketamine, gabapentin, and lidocaine, which allow for localized pain relief while reducing systemic side effects.1

In veterinary medicine, animals often require formulations that differ in dosage strength, form, or flavor from those approved for human use. For example, a cat might receive a tuna-flavored liquid instead of a bitter pill.5 Compounding can also be used to create custom treatments for skin conditions such as eczema, psoriasis, or acne, often by adjusting the base or active ingredient to improve tolerability and efficacy.1

Sterile Compounding Pharmacy: How Sterile Medications are Made at Town & Country Compounding

Regulation and Oversight

Unlike FDA-approved drugs, compounded medications are not subject to pre-market approval. However, these therapies are regulated by a combination of federal and state laws aimed at ensuring safety and quality.2

In the U.S., compounding is governed under distinct federal and state frameworks, with practices divided into two primary categories. These include 503A pharmacies, which are traditional pharmacies that compound medications according to patient-specific prescriptions. Importantly, these pharmacies must comply with U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) standards, which regulate drug quality, but are exempt from certain FDA manufacturing regulations.6

Created after the 2012 fungal meningitis outbreak, 503B outsourcing facilities facilitate large-scale sterile compounding without patient-specific prescriptions. Importantly, these pharmacies must similarly comply with current Good Manufacturing Practices and register with the FDA.6

Although the ingredients used in compounding medications are often FDA-approved, the final compounded product is not. This distinction raises concerns about product consistency, potency, and sterility, especially for sterile injectables, which carry a higher risk of contamination.8

Benefits and Controversies

Compounded medications are associated with numerous benefits, the most important of which is the ability to customize medication according to an individual’s specific needs, which can significantly enhance therapeutic outcomes. Patients also benefit from alternatives when commercially available drugs are unavailable or unsuitable.1

However, poor compounding practices can result in contamination or incorrect dosages. For example, the 2012 meningitis outbreak caused by contaminated steroid injections from the New England Compounding Center led to 64 deaths, which prompted sweeping regulatory reforms.8

Since compounded medications are not FDA-approved, they lack uniform labeling, standardization, instructions, and robust post-market surveillance.4 Compounded bioidentical hormone therapies are also widely promoted, despite limited clinical evidence supporting their efficacy or safety as compared to FDA-approved alternatives.2

The Future of Compounding

The landscape of pharmaceutical compounding is evolving in response to regulatory, technological, and clinical trends. As a result, the U.S. FDA and Pharmacopeia continue to update guidelines on how to improve quality control in both sterile and non-sterile compounding.6

Drug shortages and personalized medicine trends are increasing the demand for compounded medications. The use of compounded medications in veterinary care and alternative medicine is also expanding the scope of this production process. Meanwhile, improvements in educating pharmacists about compounding and digital tools for compounding protocols are improving safety and consistency.3

Conclusions

As the healthcare system continues to evolve toward personalized and precision medicine, the role of compounding will likely grow. However, ensuring robust regulatory frameworks, ongoing pharmacist training, and public health vigilance will be critical to maximizing benefits while minimizing risks.

References

- Carvalho, M., & Almeida, I. F. (2022). The Role of Pharmaceutical Compounding in Promoting Medication Adherence. Pharmaceuticals, 15(9), 1091. DOI: 10.3390/ph15091091, https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8247/15/9/1091

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2018). Compounding and the FDA: Questions and Answers. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/compounding-and-fda-questions-and-answers [Accessed on May 20, 2025]

- Dooms, M., & Carvalho, M. (2018). Compounded medication for patients with rare diseases. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 13(1), 1. DOI:10.1186/s13023-017-0741-y, https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-017-0741-y

- Gudeman, J., Jozwiakowski, M., Chollet, J., & Randell, M. (2013). Potential risks of pharmacy compounding. Drugs in R&D, 13(1), 1–8. DOI:10.1007/s40268-013-0005-9, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40268-013-0005-9

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2023, May 1). Animal Drug Compounding. https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/unapproved-animal-drugs/animal-drug-compounding [Accessed on May 20, 2025]

- Watson, C. J., Whitledge, J. D., Siani, A. M., & Burns, M. M. (2021). Pharmaceutical Compounding: a History, Regulatory Overview, and Systematic Review of Compounding Errors. Journal of Medical Toxicology, 17(2), 197–217. DOI: 10.1007/s13181-020-00814-3, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13181-020-00814-3

- Coukell A. (2014). Risks of compounded drugs. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(4), 613–614. DOI:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12812, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/1819570

- Staes, C., Jacobs, J., Mayer, J., & Allen, J. (2013). Description of outbreaks of health-care-associated infections related to compounding pharmacies, 2000-12. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 70(15), 1301–1312. DOI:10.2146/ajhp130049, https://academic.oup.com/ajhp/article/70/15/1301/5112253

Last Updated: Nov 13, 2025