The neurological underpinnings of sleepwalking

Triggers and risk factors

Clinical implications and safety concerns

Diagnosis and treatment

References

Further reading

Sleepwalking happens when an individual moves significantly during a deep state of sleep. It is also known as somnambulism, and it is defined as a type of parasomnia in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders.

Image Credit: Pixel-Shot/Shutterstock.com

Parasomnias are a collection of disorders that relate to abnormal behaviors during sleep, falling asleep, and awakening. Other examples include sleep talking, paralysis, night terrors, and auditory hallucinations like Exploding Head Syndrome.

Some people are predisposed to sleepwalking, such as due to genetic factors or parasomniac comorbidities. These predispositions can then be impacted by environmental factors, which can also trigger parasomniac events.

The neurological underpinnings of sleepwalking

There are several potential neuroscientific and psychobiological explanations for sleepwalking. Some understandings rely on neural activity, while others look to the role of the sleep cycle itself.

A study conducted by the Sleep Research Society suggests that perfusion differs in certain brain regions in those who are prone to sleepwalking compared to those who are not. Perfusion refers to the blood flow through tiny vessels across tissue, triggering the exchange of molecules through a semipermeable membrane. It can be used as a measurement of activity in the brain.

Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) was used to measure the perfusion patterns of both sleepwalkers and non-sleepwalkers after 24 hours of sleep deprivation. Trackers indicated that sleepwalkers had reduced levels of activity in several brain areas during both resting-state wakefulness and slow-wave sleep.

Areas that indicated reduced levels of perfusion in sleepwalkers spread across both cerebral and bilateral frontal regions. Increased perfusion was also found in the right parahippocampal gyrus during resting-state wakefulness when compared to their non-sleepwalking peers.

Sleep deprivation is thought to trigger somnambulic events. An adequate amount of slow-wave sleep is needed for someone to have the ability to regulate arousal and awakening properly. When an individual is sleep deprived, they may not have experienced enough slow-wave sleep to awaken properly, leading to sleep movements.

Image Credit: Chaikom/Shutterstock.com

Research indicates that it is most difficult to awaken during slow-wave sleep. This may be indicative of why sleepwalking tends to occur during this phase, as the body fails to end the sleep cycle. Slow-wave sleep happens during stage IV of non-rapid eye movement (non-REM) sleep.

Triggers and risk factors

Genetic factors may partially predict sleepwalking. However, it is difficult to determine the specific genetic material associated with it.

Some research has assessed the role of genes that play a role in the regulation of non-REM sleep, such as the adenosine deaminase gene, but a relationship has not been determined. Despite this, some genes do seem to be associated with parasomnias more generally.

An allele that may be associated with both sleepwalking and general parasomniac events is the HLA DQB1*05:01. Fifty-six patients, with eleven of them demonstrating sleepwalking behaviors, were tested. Several methods were used, including polysomnography, HLA DQB1 genotyping, and the regional matching of reference allele frequencies. The allele was found in 41% of the patients.

The severity of other sleep-related diagnoses may predispose people to sleepwalking. A large-scale cross-sectional study conducted found a positive association between somnambulism and severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA). Of the forms of parasomnia studied, sleepwalking was the only one to correlate with the severity of the OSA diagnosis.

Research indicates that sleepwalking may be more common following an episode of sleep deprivation. Sleep deprivation can impact the ability to have enough slow-wave sleep, potentially leading to a sleep debt. This may then create a window during which someone is more likely to become somnambulatory.

Clinical implications and safety concerns

Sleepwalking can lead to accidents and injuries. This means that, although such events are not necessarily common, safety should be taken into account if sleepwalking episodes begin.

There is a relative gap in the research regarding hospital admissions and sleepwalking-related injuries despite the potential risks posed. However, some research has been conducted. An analysis was published in 2016 investigating the cause of emergency department admissions to a university hospital in Switzerland over a fifteen-year period.

The study analyzed the cause of 620,000 admissions, finding that eleven of them were associated with somnambulism and trauma. The primary cause of admission was falls. Although the figures were relatively small, the impact it had on those patients was meaningful, with 36.4% of these patients requiring further treatment.

What is sleepwalking?

Sleepwalking can be a side effect of some medications. Medication-related sleepwalking has been reported with atypical antipsychotics, antidepressants, beta-blockers, gamma-aminobutyric acid modulators, and benzodiazepine receptor agonists. Although these side effects can be rare, this is a clinical consideration when prescribing medication - particularly to those with other predispositions.

Diagnosis and treatment

There are a range of different diagnoses and treatments available for chronic sleepwalkers. For some people, though, the disorder lessens over time without a specific treatment. Most diagnoses depend on biological measurements. Treatment, on the other hand, can take the form of either psychological therapies or pharmacotherapy.

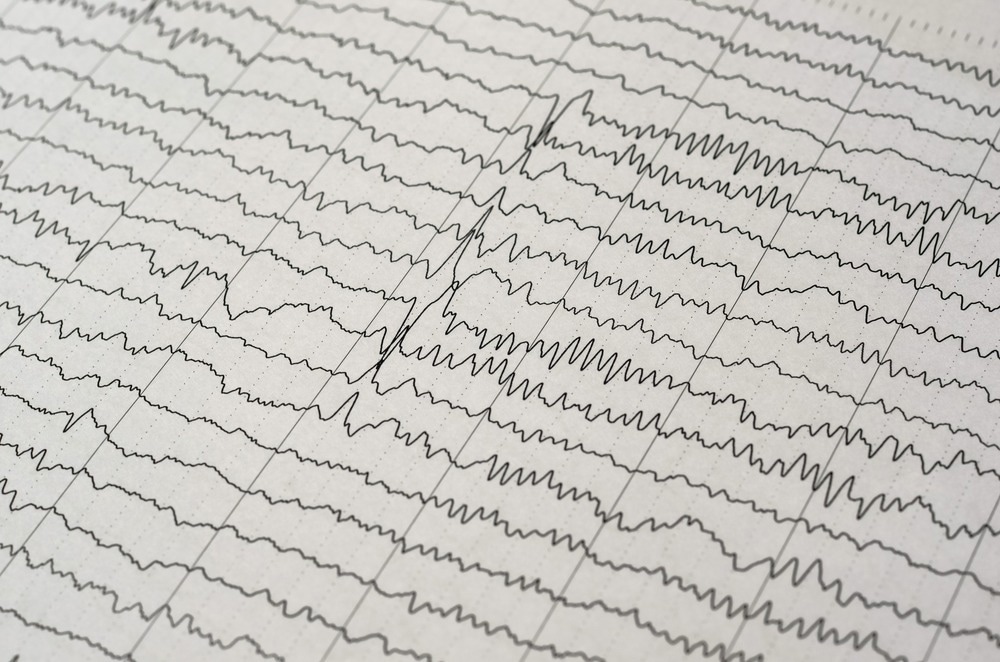

Polysomnography is one way of diagnosing sleep disorders such as somnambulism. The method is a form of sleep study made up of several types of measurement. It focuses on physiological measurements, such as electrocardiography and electroencephalography. It can also be used to diagnose comorbidities that may impact sleepwalking, such as OSA.

The Arousal Disorders Questionnaire is another potential screening tool for sleepwalking. The quotient appeared to have strong accuracy when tested in research settings. Although much further testing and approval would be needed, there may be future applications for the tool in diagnostic settings.

No singular form of treatment has been established as the gold standard. With regards to pharmacological treatments, both clonazepam and methylphenidate have shown promise in managing somnambulism. Behavioral therapies are also being tested as a form of treatment for sleepwalking, although the findings are currently mixed.

The particular conditions and causes of sleepwalking are often taken into account to provide treatment appropriately. For instance, in the case of medication-related sleepwalking, there may be the choice between managing it and altering the original course of treatment. The individual’s needs could be considered holistically to form a treatment plan.

References

- Lundetræ, R. S., Saxvig, I. W., Pallesen, S., Aurlien, H., Lehmann, S., & Bjorvatn, B. (2018). Prevalence of parasomnias in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. A registry-based cross-sectional study. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 1140.

- Scavone, G., Baril, A. A., Montplaisir, J., Carrier, J., Desautels, A., & Zadra, A. (2021). Autonomic Modulation During Baseline and Recovery Sleep in Adult Sleepwalkers. Frontiers in Neurology, 12, 680596.

- Fleetham, J. A., & Fleming, J. A. (2014). Parasomnias. Cmaj, 186(8), E273-E280.

- Copen, W. A., Lev, M. H., & Rapalino, O. (2016). Brain perfusion: computed tomography and magnetic resonance techniques. Handbook of clinical neurology, 135, 117-135.

- Desjardins, M. È., Baril, A. A., Soucy, J. P., Dang-Vu, T. T., Desautels, A., Petit, D., Montplaisir, J. & Zadra, A. (2018). Altered brain perfusion patterns in wakefulness and slow-wave sleep in sleepwalkers. Sleep, 41(5), zsy039.

- Fournier, S., Dauvilliers, Y., Warby, S. C., Labrecque, M., Zadra, A., Boucetta, S., El Gewely, M., Kaddioui, H., Lopez, R., Montplaisir, J.Y., Eric Bareke, E., Tétreault, M., & Desautels, A. (2022). Does the adenosine deaminase (ADA) gene confer risk of sleepwalking?. Journal of Sleep Research, 31(4), e13537.

- Heidbreder, A., Frauscher, B., Mitterling, T., Boentert, M., Schirmacher, A., Hörtnagl, P., Schennach, H., Massoth, C., Happe, S., Mayer, G., Young, P., & Högl, B. (2016). Not only sleepwalking but NREM parasomnia irrespective of the type is associated with HLA DQB1* 05: 01. Journal of clinical sleep medicine, 12(4), 565-570.

- Stallman, H. M., Kohler, M., & White, J. (2018). Medication induced sleepwalking: A systematic review. Sleep medicine reviews, 37, 105-113.

- Chopra, A., Patel, R. S., Baliga, N., Narahari, A., & Das, P. (2020). Sleepwalking and sleep-related eating associated with atypical antipsychotic medications: Case series and systematic review of literature. General Hospital Psychiatry, 65, 74-81.

- Sauter, T. C., Veerakatty, S., Haider, D. G., Geiser, T., Ricklin, M. E., & Exadaktylos, A. K. (2016). Somnambulism: emergency department admissions due to sleepwalking-related trauma. Western journal of emergency medicine, 17(6), 709.

- Rundo, J. V., & Downey III, R. (2019). Polysomnography. Handbook of clinical neurology, 160, 381-392.

- Bušková, J., Piško, J., Pastorek, L., & Šonka, K. (2015). The course and character of sleepwalking in adulthood: a clinical and polysomnographic study. Behavioral sleep medicine, 13(2), 169-177.

- Loddo, G., La Fauci, G., Vignatelli, L., Zenesini, C., Cilea, R., Mignani, F., Cecere, A., Mondini S., Baldelli, L., Bisulli F., Licchetta, L., Mostacci, B., Guaraldi, P., Giannini, G., Tinuper, P., & Provini, F. (2021). The Arousal Disorders Questionnaire: A new and effective screening tool for confusional arousals, Sleepwalking and Sleep Terrors in epilepsy and sleep disorders units. Sleep Medicine, 80, 279-285.

- Nigam, M., Zadra, A., Boucetta, S., Gibbs, S. A., Montplaisir, J., & Desautels, A. (2019). Successful treatment of somnambulism with OROS-methylphenidate. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 15(11), 1683-1685.

- Galbiati, A., Rinaldi, F., Giora, E., Ferini-Strambi, L., & Marelli, S. (2015). Behavioural and cognitive-behavioural treatments of parasomnias. Behavioural neurology, 2015.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Nov 24, 2023