Introduction

Food sources

Mechanisms of action

Benefits for skin health

Eye health support

Brain and cognitive effects

Safety and intake considerations

Special groups and safety data

References

Further reading

This evidence-driven review explains how marine-derived astaxanthin (ASX) works at the molecular and clinical level to protect skin, vision, and cognitive function while clarifying what human trials actually support.

Image Credit: DIVA.photo / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: DIVA.photo / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

ASX is a marine xanthophyll carotenoid primarily produced by microalgae like Haematococcus pluvialis, which accumulates the pigment under environmental stress. Dietary ASX can be obtained through seafood, including salmon, trout, shrimp, and krill.1

Natural ASX occurs predominantly as esterified stereoisomers (mainly 3S,3′S), whereas synthetic astaxanthin consists of a mixture of stereoisomers and is non-esterified.1,2 These structural differences influence chemical stability and tissue distribution, although human bioavailability is primarily determined by formulation and co-ingested dietary lipids rather than esterification status alone.2,3

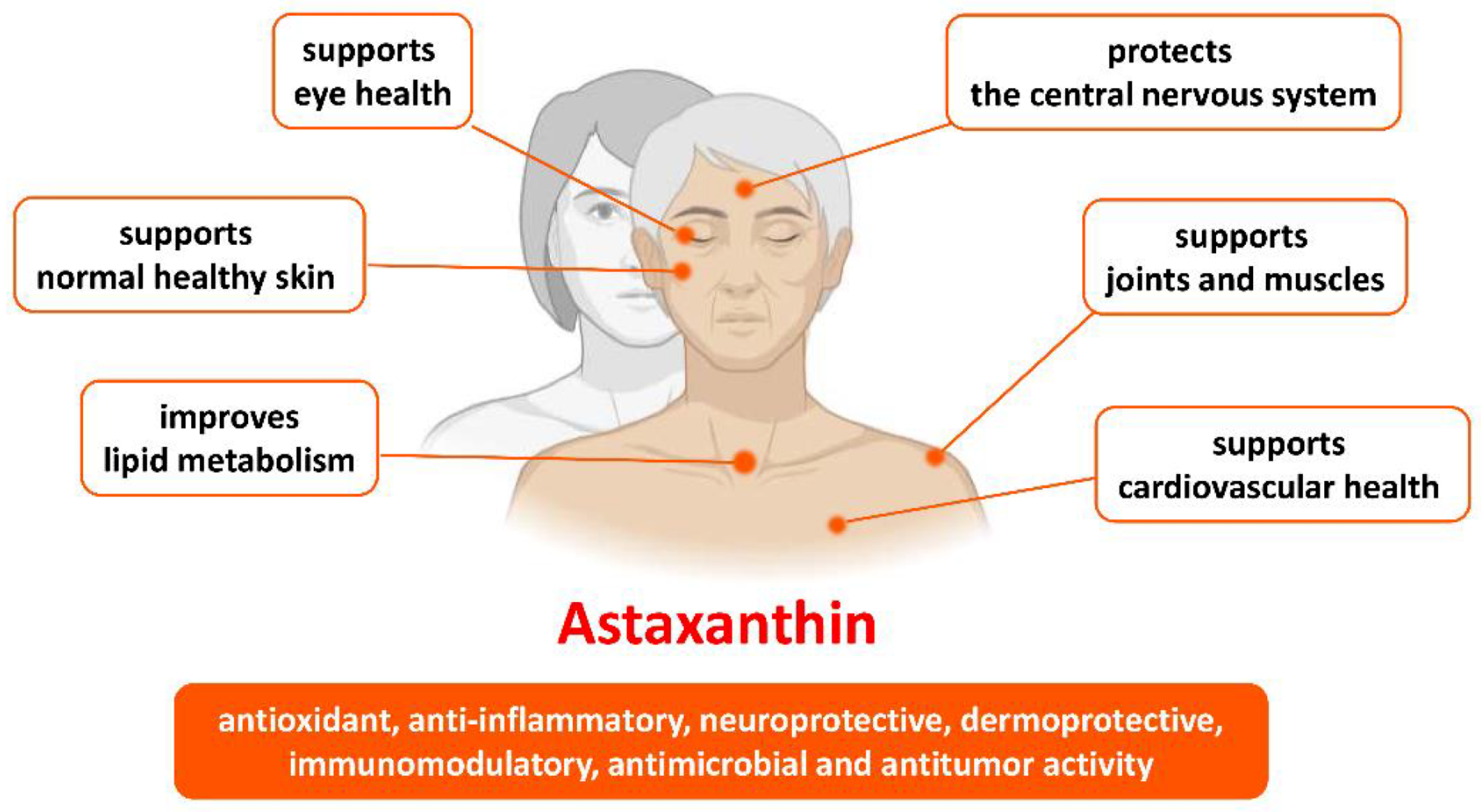

Benefits of astaxanthin in health and age-related conditions.2

Food sources

Wild salmon is one of the richest natural sources of ASX, with sockeye salmon containing approximately 26–38 mg/kg of ASX in the flesh. This is significantly higher than the ASX concentrations found in chum salmon or farmed Atlantic salmon, which typically range from 6–8 mg/kg due to dietary differences.1,13

Other fish species, including rainbow trout and red seabream (Pagrus major), accumulate ASX from plankton-rich diets and serve as other notable dietary sources. Crustaceans like shrimp, krill, crab, and crayfish are also rich in ASX, which is primarily concentrated in their shells.1

Microalgae remain the most concentrated natural producers of ASX, with H. pluvialis accumulating up to ~3–5% of dry biomass under stress conditions.1,4 This species is the principal source approved globally for human supplements, while other organisms such as Chlorella zofingiensis, Chlorococcum spp., and Phaffia rhodozyma are mainly used in feed or experimental nutraceutical contexts.3,4

Mechanisms of action

ASX is a potent singlet-oxygen quencher and lipid-phase antioxidant, demonstrating higher in vitro antioxidant capacity than β-carotene, lutein, and α-tocopherol. However, comparative antioxidant “multipliers” (e.g., thousands-fold stronger than vitamin C) are derived from chemical assays and should not be interpreted as equivalent biological potency in humans.2,3,4

The hydrophilic end of ASX scavenges free radicals at membrane surfaces, whereas the lipophilic polyene chain spans lipid bilayers, reducing lipid peroxidation and preserving membrane integrity.1–3

ASX modulates redox-sensitive signaling pathways, including NF-κB, thereby reducing the expression of inflammatory mediators. Human trials report reductions in oxidative stress biomarkers such as malondialdehyde and lipid hydroperoxides, alongside increases in endogenous antioxidant defenses, including superoxide dismutase.2,9

Preclinical and human pharmacokinetic data indicate that ASX can cross the blood–brain barrier, supporting its potential role in neural protection.2,10

Image Credit: Tatjana Baibkova / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Tatjana Baibkova / Shutterstock.com

Benefits for skin health

ASX has photoprotective properties due to its ability to mitigate UV-induced oxidative damage. Clinical studies show that oral ASX (typically 4–12 mg/day for 8–16 weeks) can reduce UV-induced erythema, improve skin moisture, and support barrier function.1,5,6

Mechanistic studies demonstrate that ASX suppresses UV-induced matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) expression and inflammatory cytokine release, thereby limiting collagen degradation.6

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicate moderate but consistent improvements in skin elasticity and hydration, while effects on wrinkle depth are more variable and study-dependent.7

Eye health support

Oxidative stress contributes to retinal aging and visual fatigue. Supplementation with ASX (typically 4–9 mg/day) has been shown to improve markers of oxidative balance in ocular tissues and enhance visual performance in adults exposed to prolonged work at visual display terminals.1,8

Randomized controlled trials in adults ≥40 years report improvements in visual acuity and accommodative function, with benefits attributed to reduced oxidative stress and improved retinal microcirculation.8

Brain and cognitive effects

ASX targets oxidative and inflammatory pathways implicated in cognitive aging.

Human randomized controlled trials report modest improvements in memory and psychomotor performance with doses of 6–12 mg/day for 8–12 weeks, particularly in middle-aged and older adults.9–11

These cognitive effects are accompanied by improvements in systemic oxidative markers, suggesting that enhanced redox balance may contribute to observed functional outcomes.9,10

Evidence for disease-modifying effects in neurodegenerative disorders remains preliminary, with current support derived mainly from animal models and small human trials.3,12

Image Credit: Madeleine Steinbech / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Madeleine Steinbech / Shutterstock.com

Safety and intake considerations

The EFSA considers the combined intake of up to 8 mg/day of ASX from diet and supplements to be safe for adults, corresponding to an acceptable daily intake of 0.2 mg/kg body weight.15

Clinical studies involving more than 2,000 participants report good tolerability at supplemental doses of 4–12 mg/day for periods up to one year, with no serious adverse effects observed.3,15

Special groups and safety data

Available data do not indicate safety concerns for healthy adults; however, evidence is insufficient for pregnancy, lactation, and pediatric use.15

Caution is advised for individuals using antihypertensive, anticoagulant, or antidiabetic medications due to potential additive physiological effects.3

References

- Ambati, R. R., Moi, P. S., Ravi, S., & Aswathanarayana, R. G. (2014). Astaxanthin: Sources, Extraction, Stability, Biological Activities and Its Commercial Applications - A Review. Marine Drugs 12(1); 128. DOI: 10.3390/md12010128. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-3397/12/1/128.

- Bjørklund, G., Gasmi, A., Lenchyk, L., et al. (2022). The Role of Astaxanthin as a Nutraceutical in Health and Age-Related Conditions. Molecules 27(21); 7167. DOI: 10.3390/molecules27217167. https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/27/21/7167.

- Donoso, A., González-Durán, J., Muñoz, A. A., et al. (2021). Therapeutic uses of natural astaxanthin: An evidence-based review focused on human clinical trials. Pharmacological Research 166. DOI: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105479. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1043661821000633

- Patil, A. D., Kasabe, P. J., & Dandge, P. B. (2022). Pharmaceutical and nutraceutical potential of natural bioactive pigment: astaxanthin. Natural Products and Bioprospecting 12. DOI: 10.1007/s13659-022-00347-y. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13659-022-00347-y.

- Ito, N., Seki, S., & Ueda, F. (2018). The Protective Role of Astaxanthin for UV-Induced Skin Deterioration in Healthy People - A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 10(7); 817. DOI: 10.3390/nu10070817. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/10/7/817.

- Tominaga, K., Hongo, N., Fujishita, M., et al. (2017). Protective effects of astaxanthin on skin deterioration. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition 61(1); 33. DOI: 10.3164/jcbn.17-35. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jcbn/61/1/61_17-35/_article.

- Zhou, X., Cao, Q., Orfila, C., et al. (2021). Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Effects of Astaxanthin on Human Skin Ageing. Nutrients 13(9); 2917. DOI: 10.3390/nu13092917. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/13/9/2917.

- Sekikawa, T., Kizawa, Y., Li, Y., & Miura, N. (2022). Effects of diet containing astaxanthin on visual function in healthy individuals: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel study. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition 72(1); 74. DOI: 10.3164/jcbn.22-65. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jcbn/72/1/72_22-65/_article

- Queen, C. J., Sparks, S. A., Marchant, D. C., & McNaughton, L. R. (2023). The Effects of Astaxanthin on Cognitive Function and Neurodegeneration in Humans: A Critical Review. Nutrients 16(6); 826. DOI: 10.3390/nu16060826. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/16/6/826.

- Hayashi, M., Ishibashi, T., & Maoka, T. (2018). Effect of astaxanthin-rich extract derived from Paracoccus carotinifaciens on cognitive function in middle-aged and older individuals. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition 62; 195-205, DOI: 10.3164/jcbn.17-100. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jcbn/62/2/62_17-100/_article.

- Katagiri, M., Satoh, A., Tsuji, S., & Shirasawa, T. (2012). Effects of astaxanthin-rich Haematococcus pluvialis extract on cognitive function: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition 51; 102–107. DOI: 10.3164/jcbn.D-11-00017. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jcbn/51/2/51_D-11-00017/_article.

- Ito, N., Saito, H., Seki, S., et al. (2018). Effects of Composite Supplement Containing Astaxanthin and Sesamin on Cognitive Functions in People with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 62(4); 1767-1775. DOI: 10.3233/JAD-170969. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.3233/JAD-170969.

- Colombo, S. M., & Mazal, X. (2020). Investigation of the nutritional composition of different types of salmon available to Canadian consumers. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2. DOI: 10.1016/j.jafr.2020.100056. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666154320300375

- Dang, Y., Li, Z., & Yu, F. (2024). Recent Advances in Astaxanthin as an Antioxidant in Food Applications. Antioxidants 13(7); 879. DOI: 10.3390/antiox13070879. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3921/13/7/879

- EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens (NDA), Turck, D., et al. (2020). Safety of astaxanthin for its use as a novel food in food supplements. EFSA Journal 18(2). DOI: 10.2903/j.efsa.2020.5993. https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.2903/j.efsa.2020.5993.

Further Reading

Last Updated: Jan 4, 2026