Introduction

The phases of the menstrual cycle

Energy and macronutrient needs

Supporting hormones through food choices

Natural ways to reduce inflammation

Metabolism and blood sugar regulation

Phase-focused food patterns

Potential benefits and limitations of cycle-synchronized eating

Conclusions

References

Further reading

This article examines how hormonal fluctuations across the menstrual cycle influence appetite, energy intake, metabolism, and nutrient utilization. It evaluates the evidence for cycle-synchronized nutrition and emphasizes flexible, individualized dietary strategies over rigid phase-based rules.

Image Credit: E.Va / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: E.Va / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

During the menstrual cycle, hormone fluctuations can influence appetite, energy expenditure, and metabolism. Changes in endogenous estrogen and progesterone concentrations are associated with phase-dependent differences in energy intake, substrate utilization, and resting metabolic rate, which may influence physical performance and perceived fatigue.1–3

Periods of reduced energy intake during phases of lower appetite, particularly the late follicular and peri-ovulatory phases, without corresponding adjustments in physical activity may compromise energy availability, a factor linked to menstrual disturbances and impaired training adaptation in physically active individuals.1 Cycle-synchronized nutrition refers to dietary strategies that align with these physiological fluctuations, with the aim of supporting metabolic stability, symptom management, and overall nutritional adequacy across the cycle.

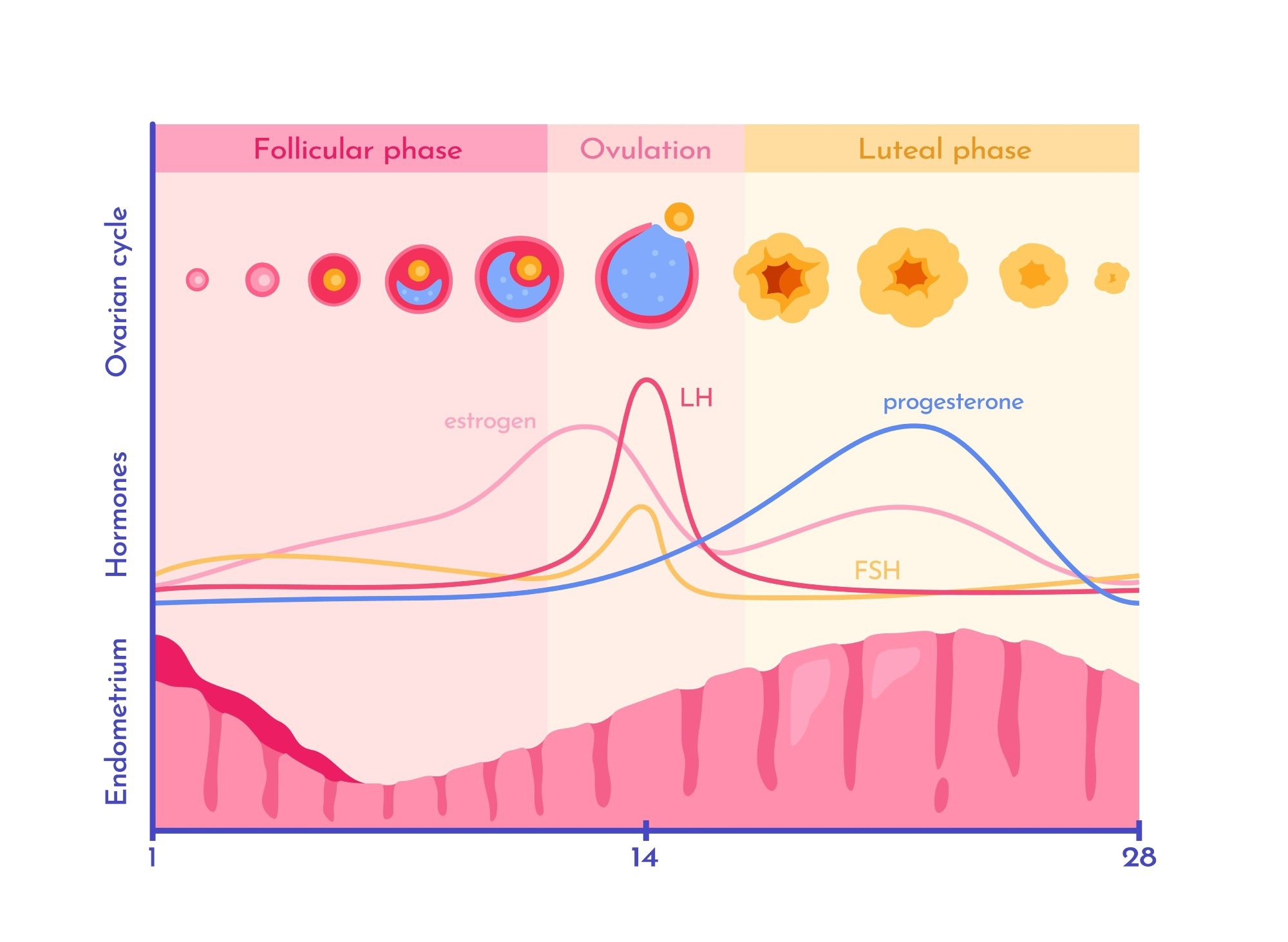

The phases of the menstrual cycle

The menstrual cycle comprises the menstrual (early follicular), follicular, ovulatory, and luteal phases, each characterized by distinct estrogen and progesterone profiles. The menstrual or early follicular phase typically spans days one through five and is associated with menstrual bleeding and low concentrations of both hormones.

During the late follicular and ovulatory phases, estrogen concentrations rise to a peak while progesterone remains low, generally below 6.4 nmol/L. Following ovulation, progesterone increases substantially during the mid-luteal phase, often exceeding 16 nmol/L, while estrogen reaches a smaller secondary peak before both hormones decline prior to the next cycle.1,2

Estrogen is associated with appetite suppression and increased carbohydrate oxidation, whereas progesterone is linked to increased appetite, higher resting energy expenditure, and a shift toward greater fat and protein utilization. These hormonal effects help explain population-level trends in dietary intake across the cycle, although the magnitude and direction of responses vary widely between individuals and between cycles.1–3

Image Credit: mental mind / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: mental mind / Shutterstock.com

Energy and macronutrient needs

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicate that average daily energy intake is higher during the luteal phase compared with the follicular phase. Mean differences of approximately 168 kcal/day have been reported, although individual responses range from negligible differences to increases exceeding 500 kcal/day.1,2

Elevated progesterone and reduced estrogenic appetite suppression during the luteal phase are associated with increased hunger, food cravings, and a modest rise in resting metabolic rate. Conversely, peak estrogen concentrations around ovulation are often associated with lower spontaneous energy intake.2,3

Observational studies also report greater consumption of fat-dense and energy-dense foods during the luteal phase. However, these associations are not universal and are influenced by study design, dietary assessment methods, physical activity levels, and inter-individual variability.1,4

Supporting hormones through food choices

Dietary patterns influence hormonal and reproductive health through micronutrient availability, inflammatory regulation, and metabolic signaling. Cross-sectional and observational studies show that individuals with menstrual disorders often report lower intakes of protein, vitamin D, zinc, magnesium, and calcium, alongside higher intakes of refined carbohydrates and added sugars.5,6

Adequate protein and unsaturated fats contribute to endocrine function by supporting hormone synthesis, cell signaling, and anti-inflammatory pathways. Higher protein intake has been associated with reduced symptom severity in some populations, while omega-3 fatty acids from fish, seeds, nuts, and olive oil have demonstrated modest benefits for dysmenorrhea and inflammatory markers.6,15

Plant-derived phytoestrogens from soy, flaxseeds, legumes, and whole grains can interact with estrogen receptors, exhibiting weak estrogenic or anti-estrogenic effects depending on hormonal context and dose.7,8 The physiological impact of phytoestrogens is further modified by gut microbiota composition, habitual intake, life stage, and baseline endogenous hormone levels, resulting in heterogeneous responses across individuals.8

Dietary fiber supports estrogen metabolism by promoting fecal excretion and reducing enterohepatic recirculation. Fiber-rich diets are also associated with improved insulin sensitivity, gut microbiome diversity, and metabolic health.9

Natural ways to reduce inflammation

Obesity, insulin resistance, and excess caloric intake contribute to chronic low-grade inflammation, which is associated with reproductive disorders such as polycystic ovary syndrome.11 Anti-inflammatory dietary patterns may mitigate these effects.

The Mediterranean dietary pattern - rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, olive oil, nuts, and fish - is consistently associated with lower concentrations of inflammatory biomarkers, including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. These benefits are attributed to monounsaturated fats, omega-3 fatty acids, fiber, and polyphenols.

Antioxidant-rich foods reduce oxidative stress associated with hormonal fluctuations. Polyphenols, carotenoids, and vitamin E found in fruits, vegetables, nuts, and olive oil neutralize reactive oxygen species and protect cellular membranes from lipid peroxidation.12

Fluctuations in glycemic control across the menstrual cycle may influence perceived energy, mood, and food cravings, particularly during the late luteal phase. While direct phase-specific glucose measurements in free-living populations are limited, maintaining stable postprandial glucose responses supports overall metabolic and cognitive function.13

Meals combining complex carbohydrates with protein and fats slow gastric emptying and glucose absorption, reducing glycemic variability. Whole grains, legumes, and fiber-rich vegetables contribute to these effects.

Stable glucose availability is essential for brain function, as glucose serves as the primary substrate for cognition, attention, and mood regulation. Diets emphasizing complex carbohydrates over refined sugars are associated with fewer cravings and improved emotional stability.13

Fiber fermentation by gut microbiota produces short-chain fatty acids, which contribute to appetite regulation, anti-inflammatory signaling, and gut–brain communication. Evidence for the use of specific spices such as turmeric and cinnamon in alleviating premenstrual symptoms remains preliminary and is largely derived from small or short-duration studies.12,15

Phase-focused food patterns

Hormonal fluctuations across the menstrual cycle influence appetite, energy expenditure, and nutrient utilization. Phase-focused eating is best interpreted as a flexible, symptom-responsive framework rather than a rigid dietary prescription.1,14

Image Credit: KucherAV / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: KucherAV / Shutterstock.com

Menstrual phase

Iron-rich foods such as legumes, leafy greens, lean meats, and fortified grains help replenish iron losses associated with menstruation. Vitamin C enhances non-heme iron absorption, while anti-inflammatory foods like fatty fish, ginger, and turmeric may reduce dysmenorrhea severity.14,15

Follicular phase

Rising estrogen levels coincide with improved insulin sensitivity and lower appetite in many individuals. Emphasizing nutrient-dense carbohydrates, lean proteins, and unsaturated fats supports metabolic efficiency and training adaptation.1,12

Ovulatory phase

Protein- and antioxidant-rich foods - including fish, eggs, legumes, berries, and leafy greens - support cellular repair and micronutrient sufficiency during ovulation, when energy intake is often lowest.1

Luteal phase

Higher resting metabolic rate and appetite during the luteal phase may increase energy needs. Balanced macronutrient intake, fiber-rich carbohydrates, and adequate magnesium and calcium are associated with improved blood glucose control and reduced premenstrual symptoms.9,14,15

Potential benefits and limitations of cycle-synchronized eating

A 2024 systematic review of 28 experimental studies reported that targeted nutritional interventions - including vitamin D, calcium, magnesium, zinc, and curcumin - were frequently associated with reductions in menstrual-related symptoms such as pain and fatigue, though study quality, intervention dosage, and outcome measures varied substantially.15

Physiological evidence supports phase-related changes in appetite, metabolism, and energy intake. However, controlled clinical trials directly testing structured cycle-synchronized dietary patterns remain scarce, limiting the ability to draw causal conclusions.1,2

High inter-individual variability suggests that rigid phase-based dietary prescriptions are unlikely to be universally effective. Individualized approaches that account for symptoms, preferences, and lifestyle demands are more consistent with current evidence.1

Conclusions

Cycle-synchronized nutrition integrates evidence on hormonal and metabolic fluctuations with practical dietary considerations. Research confirms modest, phase-related shifts in appetite, energy intake, and metabolic rate, but also highlights substantial variability between individuals and cycles.1–3

Rather than rigid phase-specific diets, adaptable nutrition strategies grounded in dietary adequacy, anti-inflammatory food patterns, micronutrient sufficiency, and glycemic stability are most strongly supported by current evidence.1,15

References

- Rogan, M. M., & Black, K. E. (2023). Dietary energy intake across the menstrual cycle: A narrative review. Nutrition Reviews 81(7); 869-886. DOI: 10.1093/nutrit/nuac094. https://academic.oup.com/nutritionreviews/article/81/7/869/6823870

- Tucker, J. A., McCarthy, S. F., Bornath, D. P., et al. (2025). The Effect of the Menstrual Cycle on Energy Intake: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Nutrition Reviews 83(3); e866-e876. DOI: 10.1093/nutrit/nuae093. https://academic.oup.com/nutritionreviews/article/83/3/e866/7713894

- Benton, M. J., Hutchins, A. M., & Dawes, J. J. (2020). Effect of menstrual cycle on resting metabolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 15(7). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236025. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0236025

- Gorczyca, A. M., Sjaarda, L. A., Mitchell, E. M., et al. (2016). Changes in macronutrient, micronutrient, and food group intakes throughout the menstrual cycle in healthy, premenopausal women. European Journal of Nutrition 55(3); 1181-1188. DOI: 10.1007/s00394-015-0931-0. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00394-015-0931-0

- Güzeldere, H. K. B., Efendioglu, E., H., Mutlu, S., et al. (2024). The relationship between dietary habits and menstruation problems in women: a cross-sectional study. BMC Women's Health 24; 397. DOI: 10.1186/s12905-024-03235-4. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12905-024-03235-4

- Siminiuc, R., & Ţurcanu, D. (2023). Impact of nutritional diet therapy on premenstrual syndrome. Frontiers in Nutrition 10. DOI: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1079417. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/nutrition/articles/10.3389/fnut.2023.1079417/full

- Shanmugaloga, S., & Shilpa, P N. (2024). Phytoestrogens: Unlocking the Power of Plant Based Estrogens. Journal of Ayurveda Integrated Medical Sciences 9(6); 164-167. DOI: 10.21760/jaims.9.6.25. https://jaims.in/jaims/article/view/3273.

- Domínguez-López, I., Yago-Aragón, M., Salas-Huetos, A., et al. (2020). Effects of Dietary Phytoestrogens on Hormones throughout a Human Lifespan: A Review. Nutrients 12(8); 2456. DOI: 10.3390/nu12082456. https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/12/8/2456

- Bulsiewicz, W. J. (2023). The Importance of Dietary Fiber for Metabolic Health. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 17(5); 639. DOI: 10.1177/15598276231167778. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/15598276231167778

- Calcaterra, V., Verduci, E., Stagi, S., & Zuccotti, G. (2024). How the intricate relationship between nutrition and hormonal equilibrium significantly influences endocrine and reproductive health in adolescent girls. Frontiers in Nutrition 11. DOI: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1337328. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/nutrition/articles/10.3389/fnut.2024.1337328/full

- Mazza, E., Troiano, E., Ferro, Y., et al. (2023). Obesity, Dietary Patterns, and Hormonal Balance Modulation: Gender-Specific Impacts. Nutrients 16(11). DOI: 10.3390/nu16111629, https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/16/11/1629

- Hewlings, S. J., & Kalman, D. S. (2017). Curcumin: A Review of Its’ Effects on Human Health. Foods 6(10); 92. DOI: 10.3390/foods6100092. https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/6/10/92

- Arshad, M. T., Maqsood, S., Altalhi, R., et al. (2025). Role of Dietary Carbohydrates in Cognitive Function: A Review. Food Science & Nutrition 13(7). DOI: 10.1002/fsn3.70516. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/fsn3.70516

- Archana, B., Singh, N., Mishra, A. K., & Nanda, A. (2025). A Review on Nutritional Requirements During Menstrual Cycle Phases. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.15519624. https://www.ijpsjournal.com/article/A+Review+on+Nutritional+Requirements+During+Menstrual+Cycle+Phases

- Brown, N., Martin, D., Waldron, M., et al. (2023). Nutritional practices to manage menstrual cycle related symptoms: a systematic review. Nutritional Research Reviews 37(2); 352-375. DOI: 10.1017/S0954422423000227. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/nutrition-research-reviews/article/nutritional-practices-to-manage-menstrual-cycle-related-symptoms-a-systematic-review/F28E2DC079C7DC2F1AC07A0EFCDE0DE1

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 8, 2026