Introduction

What are UPFs?

An overview of brain development

How UPFs affect the brain

Human evidence

Practical guidance for parents

References

Further reading

Ultra-processed foods (UPF) can interfere with healthy brain development, emotional regulation, and cognitive function in children and adolescents. Reducing UPF intake and prioritizing nutrient-dense whole foods supports better learning, mood stability, and long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Image Credit: ibragimova / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: ibragimova / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are industrial formulations made from refined substances extracted from whole foods, with flavorings, colors, and cosmetic additives, and minimal intact food content. This article explains how UPFs may affect children’s brain development, metabolic regulation, emotional health, and attention during critical developmental windows.3

What are UPFs?

UPFs are not modified whole foods; instead, these products are formulations made mostly or entirely from substances derived from foods, with little or no intact food content. Typical ingredients of UPFs include refined starches, added sugars, fats, and salt, combined with industrial additives such as emulsifiers, stabilizers, colors, flavors, flavor enhancers, and non-sugar sweeteners.

Manufacturing of UPFs often uses processes with no culinary equivalent, such as hydrogenation, hydrolysation, extrusion, molding, and pre-processing for frying.2 These processes lead to the production of convenient and packaged items that are durable, aggressively marketed, and designed to be hyper-palatable.

Common examples of UPFs include soft drinks, sweet or savory packaged snacks, reconstituted meat products, and pre-prepared frozen dishes. Diets high in these products are often energy-dense, high in unhealthy fats, refined starches, free sugars, and sodium, while also low in dietary fiber and key micronutrients.

Many UPFs also provide a high glycaemic load, which can interfere with satiety signaling and increase the risk of excessive caloric intake and weight gain in children.6 The formulation and marketing of UPFs often promote overconsumption, which displaces minimally processed foods and freshly prepared meals from daily eating patterns.2

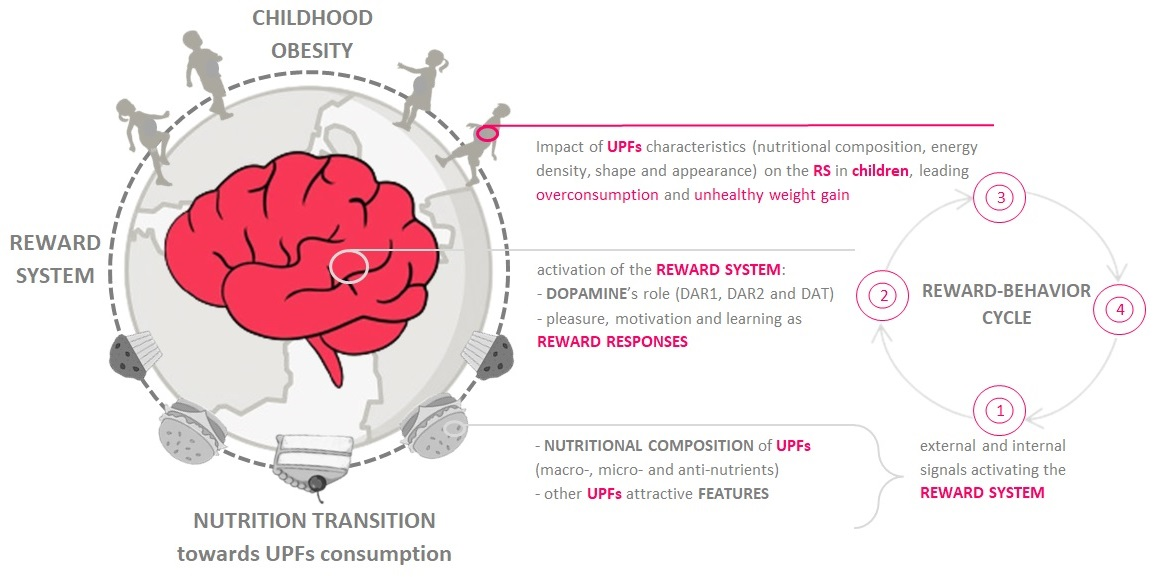

Ultra-processed food, reward system and childhood obesity1

An overview of brain development

During early childhood, myelination and synapse formation accelerate, especially from the late fetal period into early neonatal life, to support cognition, reward regulation, and sensory processing. Long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are involved in synaptogenesis and membrane function, whereas dietary choline contributes to neurotransmission and membrane phospholipids. Iron is also essential for myelination and neurotransmitter synthesis, with its deficiency leading to disrupted hippocampal and frontal-cortical energy metabolism.

Zinc supports presynaptic release and structural growth in the cerebellum, limbic system, and cortex. Together with adequate protein and B vitamins, these nutrients protect neuroanatomy, neurochemistry, and neurophysiology during periods of rapid plasticity.3

UPFs often replace nutrient-dense foods in children’s diets, reducing intake of iron, zinc, omega-3 fatty acids, and B vitamins that are needed for optimal brain maturation.6 Prioritizing foods rich in omega-3 PUFAs, iron, zinc, B-vitamins, and choline during infancy and early childhood is crucial for myelination, efficient synaptic signaling, and healthy executive and emotional development, while limiting UPFs reduces the risk of deficits that can have lasting cognitive effects.3

How UPFs affect the brain

Refined carbohydrates and fast-absorbed sugars in UPFs directly contribute to fluctuations in blood glucose levels that interfere with reward and satiety signaling, and they also promote cravings, distractibility, and weaker cognitive control. Chronic UPF exposure leads to inflammation and oxidative stress in the brain, with cytokine-driven neuroinflammation associated with mood symptoms, impaired learning, and long-term cognitive decline.3,4

UPFs disrupt microbiome diversity and increase intestinal permeability, thereby allowing inflammatory molecules to enter circulation and induce neuroinflammation. The microbiome produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) from dietary fiber that can cross the blood-brain barrier to regulate energy homeostasis and brain function. UPF-linked dysbiosis reduces SCFA levels and alters neurochemistry, including serotonin and brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which are critical for emotional regulation, learning, and memory.3,4

Food emulsifiers, such as carboxymethylcellulose and polysorbate-80, also affect microbiota composition, reduce the integrity of the mucus barrier, and increase lipopolysaccharide and flagellin levels, all of which contribute to low-grade systemic inflammation. To this end, animal studies report reduced microbial diversity, expansion of pro-inflammatory taxa, and pro-inflammatory metabolism after emulsifier exposure.3,4

UPF consumption in early life may also influence reward pathways, including dopaminergic signaling, thereby altering eating behaviors and preferences for highly palatable foods.1,3

Glycemic volatility, cytokine-mediated neuroinflammation, and gut-brain axis disruption, exacerbated by additive-induced microbiome changes and reduced SCFAs, demonstrate how high-UPF diets correlate with mood instability, poor focus, and weaker cognitive performance across the life course.3,4

Human evidence

Across observational studies, higher UPF intake correlates with poorer cognitive performance in youth and young adults. Evidence from large pediatric and university cohorts shows that UPF consumption is linked to lower executive function, decreased physical and mental quality of life, and higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms.5,6 Diets high in UPFs can impair neurodevelopment and cognitive performance during adolescence, with cohort data in European youths linking each 10% rise in UPF energy intake to reduced composite executive-function scores, independent of adiposity and socioeconomic status.3,5

Higher UPF exposure is also associated with greater mental distress and lower health-related quality of life among university students.3,5 Adolescent studies have similarly confirmed that UPF consumption increases the risk of anxiety, depressive symptoms, and broader psychosocial issues.

Although observational evidence consistently shows associations, causality cannot be inferred. Factors such as sleep, stress, socioeconomic status, and screen time may influence cognitive and emotional outcomes.5 Despite these observations, most evidence is cross-sectional or observational, which are vulnerable to residual confounding. Thus, longitudinal and interventional studies are needed to determine whether lowering UPF intake improves mood, cognition, and academic outcomes.3,5

Practical guidance for parents

Parents are advised to replace chips, cookies, and sugary drinks with whole-food options like fruit, unsalted nuts, plain yogurt with fruit, popcorn, boiled eggs, or water. Prioritizing family meals that include vegetables, protein, and whole grains, parents can further reduce reliance on UPFs.6

Evidence-based pediatric guidance recommends gradual substitutions, consistent family eating routines, and reducing exposure to marketing of sugary beverages and snack foods. For school or work lunches, minimally processed combinations such as meat with vegetables, fresh fruit, and plain yogurt are ideal, while avoiding packaged desserts and sweetened beverages. These family-centered, stepwise changes are easier to sustain and align with pediatric counseling evidence on reducing UPF exposure.6

References

- Calcaterra, V., Cena, H., Rossi, V., et al. (2023). Ultra-Processed Food, Reward System and Childhood Obesity. Children 10(5). DOI:10.3390/children10050804, https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9067/10/5/804

- Monteiro, C. A., Cannon, G., Moubarac, J. C., et al. (2018). The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutrition 21(1); 5-17. DOI:10.1017/S1368980017000234, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/public-health-nutrition/article/un-decade-of-nutrition-the-nova-food-classification-and-the-trouble-with-ultraprocessing/2A9776922A28F8F757BDA32C3266AC2A

- Mottis, G., Kandasamey, P., & Peleg-Raibstein, D. (2025). The consequences of ultra-processed foods on brain development during prenatal, adolescent and adult stages. Frontiers in Public Health 13. DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2025.1590083, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1590083

- Rondinella, D., Raoul, P. C., Valeriani, E., et al. (2025). The Detrimental Impact of Ultra-Processed Foods on the Human Gut Microbiome and Gut Barrier. Nutrients 17(5). DOI:10.3390/nu17050859, https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/17/5/859

- Öztürk, Y. E., & Uzdil, Z. (2025). Ultra-processed food consumption is linked to quality of life and mental distress among university students. PeerJ 13. DOI:10.7717/peerj 19931, https://peerj.com/articles/19931/

- Chamarthi, V. S., Shirsat, P., Sonavane, K., et al. (2025). The Impact of Ultra-Processed Foods on Pediatric Health. Obesity Pillars 16. DOI:10.1016/j.obpill.2025.100203, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2667368125000476

Further Reading

Last Updated: Nov 18, 2025