Humans have been studying microorganisms for hundreds of years. The first compound microscope was invented by the Janssen brothers (Johannes and Zacharias) in 1590, and formed the basis for the many discoveries that followed.

nobeastsofierce | Shutterstock

nobeastsofierce | Shutterstock

The early days of microbiology

From the 16th century onward, many theories were framed as to the way microbes flourished and spread. Contact between infected individuals was proposed in 1546 or earlier.

Once Francesco Redi debunked the theory of spontaneous generation in 1665, the scientific world was electrified by Robert Hooke’s famous theory – that all living creatures are made up of cells.

The microscope developed by Anton van Leeuwenhoek in 1674 was a significant milestone in scientific discovery as it magnified objects up to almost 300 times. He observed microbes (which he called animalcules) for the first time in droplets of pond water. He examined and described protozoa, bact, ria and fungi with accuracy.

Developing the first vaccine

In 1796 an English surgeon, Edward Jenner, developed the concept of vaccination by immunizing an eight-year-old boy against smallpox using cowpox fluid. He later injected smallpox virus repeatedly into the boy, proving that he was indeed immune.

Jenner also showed that the cowpox vaccine could be produced from the blister of a human patient rather than just the cow host. This proved the value of protective immunization against the deadly disease, which killed 10-20 percent of the population at the time.

In 1840 the British government introduced free vaccinations, abolishing the previous unsafe procedure of variolation (inoculation with smallpox virus). Smallpox vaccination spread all over Europe and even to the New World, Southeast Asia and China. A true benefactor to mankind, he was honored by many countries during his lifetime.

%2c_Physician_and_pioneer_of_vaccination%2c_vaccinating_8_year_old_James_Phipps_with_cowpox_to_provide_immunity_against_smallpox%2c_1796._-_By_Everett_Historical.jpg) Illustration of Edward Jenner (1749- 1823) vaccinating 8 year old James Phipps with cowpox to provide immunity against smallpox (Everett Historical | Shutterstock).

Illustration of Edward Jenner (1749- 1823) vaccinating 8 year old James Phipps with cowpox to provide immunity against smallpox (Everett Historical | Shutterstock).

Antiseptic surgery

Joseph Lister pioneered antiseptic surgery in 1865, while still working at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary. He did this by introducing carbolic acid, a harsh organic acid which killed most microbes, as a sterilization agent for surgical instruments and for cleaning wounds. The scientific acceptance of his work was based on the existing germ theory proposed by Pasteur’s work.

In this, his fate was unlike that of the unfortunate Ignace Semmelweiss who reduced puerperal (post-childbirth) infection to less than 1% in 1847. He did this simply by making it compulsory for doctors to wash their hands with chlorinated lime before examining each patient in his maternity wards.

Semmelweis had observed that mothers attended by doctors rather than midwives alone were three times more likely to die of childbed fever, which he suggested that doctors were to blame, spreading infection from patient to patient. Due to a theoretical underpinning, the remarkable findings were rejected and sadly, this ‘savior of mothers’ died in an asylum, just 14 days after a nervous breakdown.

As to why Lister chose carbolic acid, it was based on his observation that it reduced the foul smell from fields irrigated with sewage, but produced no adverse effects on the cattle allowed to graze there later. The massive reduction in post-operative surgery caused by this innovation has led to his being called ‘the father of modern surgery’.

Pioneers in parasitology

Major David Bruce was involved in the detection of the organism that caused Malta fever, in 1886, but it was Themistocles Zammit who actually found it, though Bruce’s name was attributed. He also discovered the cause of African sleeping sickness (Trypanosoma brucei) and its carrier, the tsetse fly.

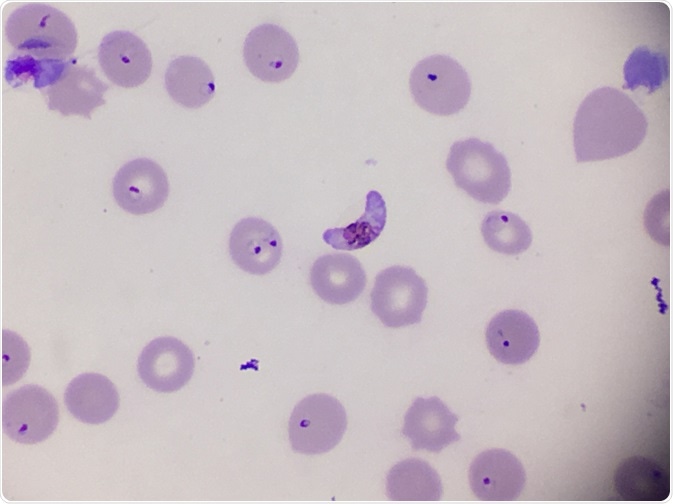

In 1897, Ronald Ross, an army major in the Indian Medical Service of the British Army, published an article simply titled “On some peculiar pigmented cells found in two mosquitoes fed on malarial blood,” which lead to him receiving the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1902. Ross was the first British scientist to receive this prestigous award.

Ross discovered that the Plasmodium parasite lived within the stomach of the mosquito fly, which helped him establish a full life cycle and prove his hypothesis that the disease is transmitted through a small amount of saliva injected into the body during mosquito bite. This allowed the health community to come up with methods of controlling malaria by controlling the number of mosquitoes. In fact, Ross suggested the first practical method of doing so, by keeping the environment free of stagnant water containers.

Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte in blood smear (Pingpoy | Shutterstock).

Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte in blood smear (Pingpoy | Shutterstock).

Antibiotics for the masses

Marjory Stephenson is another British biochemist who carried out basic research on bacterial metabolism, developing fundamental research techniques in this field. She worked with Stickland to isolate a bacterial enzyme for the first time in history, and brought to light enzyme adaptation, among other bacterial processes. She wrote more than twenty papers and one of the most important early textbooks in this field. She became the first female Fellow of the Royal Society in 1945.

In 1929 Alexander Fleming, a Scotsman, discovered penicillin. The fungus Penicillium notatum was accidentally growing on a culture of Staphylococcus aureus and inhibiting the growth of the bacterium. He examined the growth further and found that it kept many bacteria from growing.

Ernst Boris Chain, a German who migrated to Britain, earned the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1945, the year World War II ended, sharing it with his Australian colleague, Howard Florey, and with Fleming, for discovering, characterizing and developing penicillin as a drug.

The science of microbiology is still developing rapidly, and research is going on rapidly to explore the use of microbes in the treatment of cancer, to address waste management issues, and for the industrial production of many substances.

Further Reading

Last Updated: May 17, 2023