Tiny plastic fragments are turning up in milk and cheese, raising urgent questions about how our favorite dairy products travel from farm to fridge, and what we’re really eating.

Study: Assessing microplastic contamination in milk and dairy products. Image Credit: JGLmarket / Shutterstock

Study: Assessing microplastic contamination in milk and dairy products. Image Credit: JGLmarket / Shutterstock

In a recent study published in the journal npj Science of Food, a group of researchers quantified and characterized microplastic (MP) contamination in milk, fresh cheese, and ripened cheese sold in Italian supermarkets.

Background

What if your morning latte came sprinkled with tiny plastic flakes that slip past the tongue? Scientists estimate that people ingest tens of thousands of such fragments yearly, according to recent reviews, yet dairy, a staple for millions, remains understudied.

Plastics line feed bags, milking tubes, cheese molds, and retail wraps, offering countless entry points for debris smaller than 5 millimeters. While seafood and bottled water dominate MP headlines, dairy products also travel equipment-dense routes before reaching consumers.

Identifying when and where fragments accumulate could help redesign processing lines, select safer polymers, and guide smarter packaging policy. Larger, long-term investigations are still needed to pinpoint the riskiest steps and craft effective industry standards.

About the study

Investigators bought 28 commercial dairy items, such as 4 cartons of ultra-high-temperature (UHT) milk, 10 fresh cheeses aged less than 1 month, and 14 ripened cheeses matured for more than 4 months, from major northern-Italian retailers.

Products arrived on ice at the European Center for the Sustainable Impact of Nanotechnology (ECSIN) and were stored at –20°C until analysis. After thawing, 100 mL of milk or 10 g of quartered cheese underwent sequential enzymatic and alkaline digestion to dissolve organic matter.

Samples received trypsin solution, potassium hydroxide, and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) in a temperature-controlled shaker, then were vacuum-filtered through 3 μm silver membranes.

Dense particles were separated by triple flotation in saturated sodium chloride (NaCl), refiltered, and oven-dried. Each membrane was scanned with micro Fourier-Transform Infrared spectroscopy in attenuated total reflectance mode (μ-FTIR-ATR); spectra matching at least 80% confirmed polymer identity.

All work took place inside an International Organization for Standardization (ISO) class 7 cleanroom equipped with high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration. Procedural blanks never exceeded 10 fragments, and spiked-water recoveries averaged 84%, supporting analytical reliability.

Study results

MP appeared in 26 of 28 samples, demonstrating that dairy consumers ingest plastic before food even leaves the refrigerator. Across all items, scientists counted 266 particles spanning 20 polymer types. Poly(ethylene terephthalate) led detections, present in 19 samples, followed by polyethylene in 15 and polypropylene in 12.

Concentrations mirrored processing intensity: ripened cheese averaged 1,857 MP/kg, fresh cheese 1,280 MP/kg, and milk 350 MP/kg, with least-square means differing significantly at P < 0.05. These values echo earlier reports that high-fat, highly processed dairy products such as butter and milk powder harbor the greatest MP loads.

Fragments dominated particle shape, accounting for 77% of observations, whereas fibers comprised 22% and beads less than 1%. Such irregular shards likely arise from friction inside pumps and shredders or abrasion of plastic films.

Size skewed small: one-third measured 51-100 μm, and 20% fell below 50 μm. Smaller dimensions matter because tiny plastics can traverse intestinal barriers more readily than visible debris, which raises toxicological concerns but was not specifically addressed in this study.

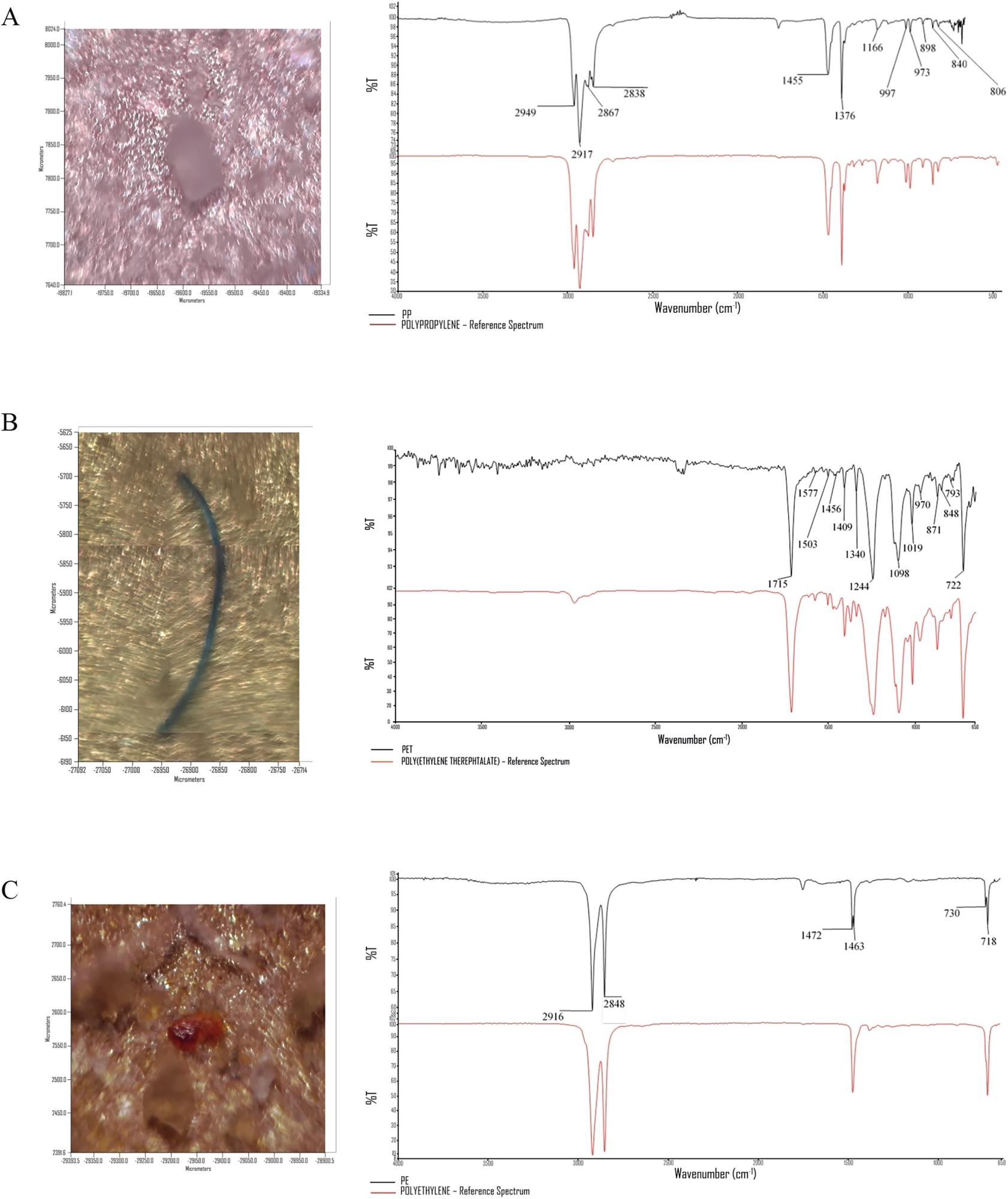

Images and Fourier-transformed infrared micro-spectroscopy in attenuated total reflectance mode analysis (μ-FTIR-ATR) spectra of three identified MP with different shapes and colors: A polypropylene, B poly(ethylene terephthalate), and C polyethylene (black line for MP spectra from dairy products, red line for MP spectra from reference libraries).

Images and Fourier-transformed infrared micro-spectroscopy in attenuated total reflectance mode analysis (μ-FTIR-ATR) spectra of three identified MP with different shapes and colors: A polypropylene, B poly(ethylene terephthalate), and C polyethylene (black line for MP spectra from dairy products, red line for MP spectra from reference libraries).

Color analysis offered origin clues: gray particles (68%) were common in polyethylene, polystyrene, and polyvinyl chloride, polymers widely used in gaskets, conveyor belts, and stretch wrap. Transparent fragments, limited to poly(ethylene terephthalate), pointed to bottle-grade plastics, while blue and red flecks suggested food-contact gloves or line markings.

Statistical dispersion, expressed as the coefficient of variation (CV), differed by polymer. Silicone showed the widest spread (CV ≈ 127%), hinting at sporadic equipment failures, whereas polyacrylate and polyvinyl chloride were more uniformly present (CV ≈ 35-38%). The consistent detection of polyacrylate underscores the need to examine recurring process aids such as cheese-coating resins.

Comparing matrices highlighted cheese-making’s concentrating effect. During curd formation, whey removal reduces mass yet traps solids, including MP. Extended aging intensifies this by evaporating moisture, explaining why ripened cheese contained five times more particles than milk.

The pattern matches studies showing that purified powders and shelf-stable spreads are MP-dense; lengthy contact with plastic molds, aging racks, and barrier wraps appears to be a critical pathway. Together, the data reveal a progressive accumulation of MP along the dairy chain, from farm tubing to supermarket shelf.

Conclusions

To summarize, MP contamination is embedded in everyday dairy products and escalates with each processing and packaging step. Ripened cheeses, celebrated for complex flavor, also concentrate the highest MP loads, many small enough to bypass gastrointestinal defenses.

Findings highlight the urgency of auditing every link in the dairy supply chain, replacing abrasion-prone polymers, bolstering clean-room standards, and developing and testing biodegradable alternatives.

Until such interventions mature, informed consumers, vigilant regulators, and proactive manufacturers share responsibility for reducing invisible plastics that journey from production line to breakfast table, safeguarding both public health and the integrity of a global food staple.