Sponsored Content by BGI GenomicsReviewed by Olivia FrostSep 13 2023

Overview of colorectal cancer in Poland

With the number of new cases and deaths associated with colorectal cancer (CRC) continuing to grow in European countries such as Poland, early screening for CRC is now more important than ever. Thanks to BGI Genomics, highly sensitive and non-invasive fecal DNA testing for CRC is much more accessible than before, allowing individuals to conveniently conduct the test within the comfort of their own homes. COLOTECT® 1.0 DNA test for CRC helps to propel the early discovery of CRC in Poland and reduce the number of cases and CRC-related deaths.

BGI Genomics: A Roundtable Discussion on Colorectal Cancer Detection

BGI Genomics: A Roundtable Discussion on Colorectal Cancer Detection from AZoNetwork on Vimeo.

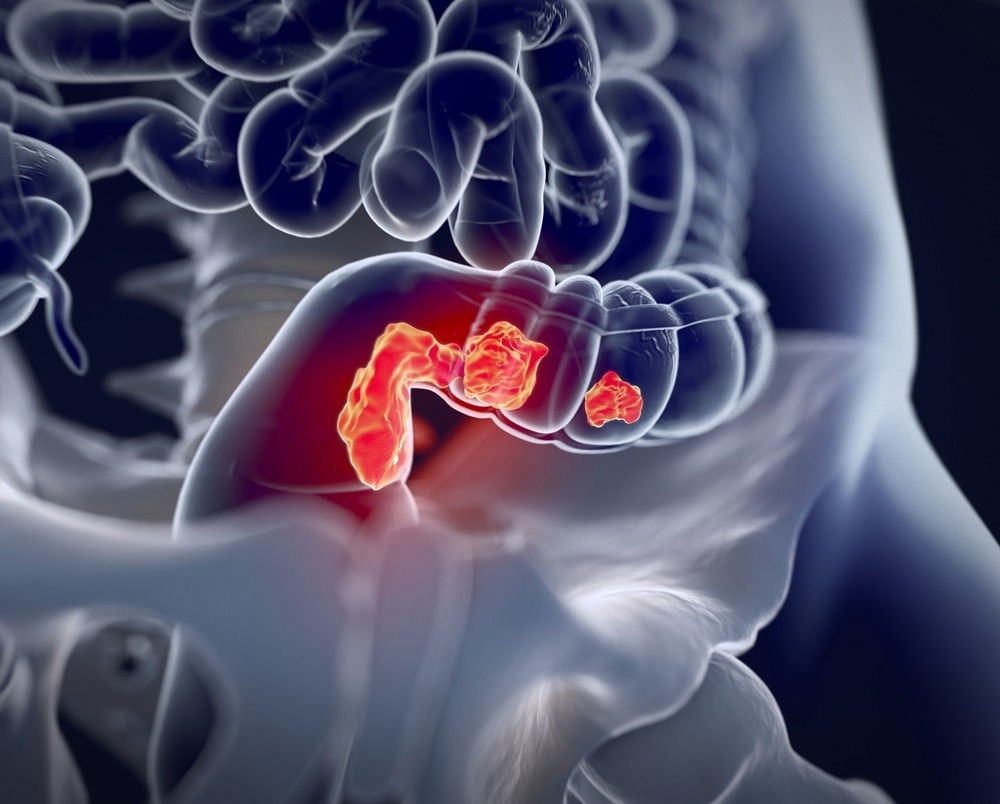

CRC is the third most common type of cancer worldwide, with approximately 1.8 – 1.9 million new cases diagnosed annually and 0.94 million deaths worldwide in 2020.1,2 Most prevalent in developed countries, relating to less healthy diets and lifestyles, it is the second most common cancer in Europe.3 In Poland, CRC is the second most predominant cause of death by cancer in both males and females. Since the 1980s, the number of cases has risen dramatically, having a 3-fold increase in women and a 5-fold increase in men in the 21st century.4 In 2014, 6,400 men and 5,000 women died due to CRC in Poland, and the overall number of CRC-related deaths is estimated to rise to almost 14,400 in 2030.5 The male-to-female gap in CRC-related mortality has also widened since the 1980s. For example, between 2010 and 2014, the mortality ratio between males and females was 1.29 – 1.38, with a predicted increase of over 1.40 each year from 2020 onwards.5

Delving a little further into the matter, an investigation into the spatial clustering of age-adjusted CRC mortalities in Poland revealed that CRC could be directly linked with tobacco use, with a greater prevalence of smokers observed in Poland’s northern and western regions. This underscores the urgency of implementing early screening initiatives in these specific areas, and this information should shape public health policies within these regions. However, patients taking part in early screening are self-selected and follow healthy diets and lifestyle choices, while patients with a higher risk of developing CRC are less likely to partake in such activities; both alcohol and tobacco users are unlikely to participate in early CRC screening; thus, there is a growing need for more targeted screening in Poland.5

Image Credit: Anatomy Image/Shutterstock.com

Compared to other European countries, the participation rate in early CRC screening in Poland is much lower. In 2019 a study showed that only 17% of the population in Poland opted to participate in early CRC screening, compared to 68% in the Netherlands and 65% in Denmark.6 In Poland, individuals more likely to participate in CRC screening tend to be older and have a high socioeconomic class, which only includes a small fraction of the population. Overall, research suggests that socioeconomic status, patient-physician communication, and local availability of health care are significantly related to knowledge of the necessity of participation in early screening for CRC in Poland. Patient-physician communication is thought to be the main factor influencing patients’ knowledge about CRC and the importance of early screening.5 Therefore, spreading more knowledge and information about the importance of early screening for CRC, as well as providing more accessible screening, in Poland is a must.

The need for early screening

Given the significant rise in CRC cases and related fatalities in Poland, along with the issues relating to the self-selected patient system, the implementation of CRC early screening is imperative to mitigate mortality rates associated with CRC. Early detection leads to better treatment efficacy, with CRC survival rates of approximately 90% for localized cancers.7 The progression of precancerous polyps (abnormal tissue growths in the colon or rectum) into cancerous tumors can take up to 10 to 15 years.8 However, most CRC cases (approximately 60%) are only diagnosed when cancer has spread to other body sites because the early stages of CRC development are generally asymptomatic.9 This presents numerous significant challenges when treating and caring for CRC patients and further highlights the necessity of early screening and diagnosis for improved treatment and patient outcomes.

Image Credit: Jo Panuwat D/Shutterstock.com

Timely screening enables the identification and removal of these polyps before their transformation into cancer, underscoring the criticality of early screening in combatting CRC in Poland. Both the government and the public in Poland are becoming more aware of the significance of these statistics, along with the necessity of early screening and detection tests. Consequently, individuals with average risk are encouraged to undergo regular screening from the age of 50 onwards; screening should start earlier for populations with a higher risk.

Direct colon visualization through a colonoscopy is thought to be the gold standard approach, with considerably high specificity (89 – 91%) and sensitivity (75 – 93%).10 However, in Poland, colonoscopies are either the only screening method available for early detection of CRC or the method of choice.11 This method is a highly invasive and potentially uncomfortable experience, accompanied by a risk of procedural complications. It is also a relatively time-consuming procedure that requires bowel preparation, making non-invasive methods more desirable. Such non-invasive methods usually involve a self-sampled stool, which is then sent off and tested for occult blood. In more recent years, the fecal immunochemical test has been used to detect human hemoglobin, which is much more sensitive than traditional guaiac-based fecal occult blood tests.12 Abnormal results from these tests can be indicative of CRC; however, the sensitivity of these tests is questionable, making them less reliable for early CRC diagnosis when compared to a colonoscopy.

Screening of fecal DNA

Due to the limited sensitivity of current methods, new non-invasive approaches complement and improve current CRC screening methods. These methods involve the identification of biomarkers specific to early CRC development.

During the initial development of CRC, affected cells display an accumulation of mutations in both the genome and epigenome. This is a multi-step process that involves the accumulation of specific mutations in oncogenes, tumor suppressors, and DNA repair genes.13 These mutations can be detected as biomarkers from patients’ fecal samples and can be used for early diagnosis when cells from precancerous/cancerous lesions shed their DNA into the patient’s stool.14

Image Credit: Billion photos/Shutterstock.com

Abnormal cells with mutated DNA display specific hypermethylation at CpG sites in the promoter region of DNA repair and/or tumor suppressor genes.14 The methylation of CpG sites is, therefore, an attractive biomarker for the early detection of CRC development, and several methylation markers specific to CRC have been identified.13 Some biomarkers have proven to be successful during clinical screening and early diagnosis of CRC, both alone or in combination with other diagnostic methods.11

One major advantage of abnormal DNA methylation is the fact that it is a positive, stable biomarker that is not masked by any normal functioning tissues nearby. 13. As a result, multiplex methylation-specific PCR (MSP) provides a highly sensitive detection method for CRC screening, where multiple loci can be assessed in a single assay. In addition to this, aberrant DNA methylation is one of the earliest molecular changes to occur during oncogenesis and can be easily detected from cfDNA (cell-free DNA), making it an extremely attractive screening technique for the early detection of CRC.15

COLOTECT® 1.0 non-invasive fecal DNA testing for CRC

As the recognition of its high diagnostic power grows, the use of methylated DNA extracted from fecal samples as a biomarker for detecting the initial phases of colorectal cancer tumors is steadily gaining popularity.16 COLOTECT® 1.0, developed by BGI Genomics, is a non-invasive fecal DNA test for the detection of CRC. This method traces the abnormal methylation of biomarkers associated with CRC using the multiplex MSP technique mentioned above.

This non-invasive, in vitro diagnostic assay qualitatively detects the abnormal methylation of certain genes in a patient’s stool sample as a biomarker for the identification of CRC. This technique is much more sensitive, relatively less costly, and is becoming central to the early detection of precancerous polyps.15 BGI Genomics’ COLOTECT® 1.0 methylation-based fecal DNA test has an overall sensitivity of 88% for identifying CRC and a sensitivity of 46% for identifying advanced precancerous lesions, with a 92% specificity for controls.17

Image Credit: mi_viri/Shutterstock.com

In addition to its high sensitivity, one of the notable advantages of COLOTECT® 1.0 is its non-restrictive nature, as it does not necessitate dietary modifications or medication adjustments prior to the test. Patients can conveniently collect stool samples in the privacy of their own homes, following the provided instructions in the kit. This screening method also boasts a short turnaround time of ten calendar days (from the time the sample arrives at the BGI lab to the time the results are reported), further enhancing its efficacy in promptly identifying early abnormal tissue.

Overall, compared to traditional colonoscopy, the COLOTECT® 1.0 is a much quicker, easier, and more convenient method for CRC detection and shows great potential in accelerating efforts for CRC early detection in Poland. BGI Genomics prides itself in providing precise, fast, convenient, and affordable early CRC tests through COLOTECT® 1.0 and looks forward to facilitating early CRC detection in Poland. With more accessible, more precise, and earlier detection, the future looks brighter in terms of reducing CRC incidences and related mortalities in Poland.

Disclaimer:

- The content is provided for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute providing medical advice or professional services. It should not be used for diagnosing or treating a health problem or disease, and those seeking personal medical advice should consult with a licensed physician.

- The product described or shown is only available in certain countries.

References and Further Reading

- World Cancer Research Fund Organisation. 2020. Colorectal Cancer Rates, https://www.wcrf.org/cancer-trends/colorectal-cancer-statistics/.

- Xi, Y. and Xu, P. 2021. Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Translational oncology. 14(10), p.101174.

- Quirke, P., Risio, M., Lambert, R., von Karsa, L. and Vieth, M. 2012. International Agency for Research on Cancer. European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. –Quality assurance in pathology in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. Endoscopy. 44(Suppl 3), pp.SE116-S130.

- Religioni, U. 2020. Cancer incidence and mortality in Poland. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health. 8(2), pp.329-334.

- Czaderny, K. 2019. Increasing deaths from colorectal cancer in Poland-insights for optimising colorectal cancer screening in society and space. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine. 26(1).

- Navarro, M., Nicolas, A., Ferrandez, A. and Lanas, A. 2017. Colorectal cancer population screening programs worldwide in 2016: An update. World journal of gastroenterology. 23(20), p.3632.

- Burra, P., Bretthauer, M., Buti Ferret, M., Dugic, A., Fracasso, P., Leja, M., Matysiak Budnik, T., Michl, P., Ricciardiello, L., Seufferlein, T. and van Leerdam, M. 2022. Digestive cancer screening across Europe. United European Gastroenterology Journal. 10(4), pp.435-437.

- Sponsored Content by BGI Genomics (2023) How fecal DNA testing can help with early detection of colorectal cancer, News. Available at: https://www.news-medical.net/whitepaper/20230210/How-Fecal-DNA-Testing-can-help-with-Early-Detection-of-Colorectal-Cancer.aspx

- Siegel, R.L., Miller, K.D., Goding Sauer, A., Fedewa, S.A., Butterly, L.F., Anderson, J.C., Cercek, A., Smith, R.A. and Jemal, A. 2020. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 70(3), pp.145-164.

- Lin, J.S., Piper, M.A., Perdue, L.A., Rutter, C.M., Webber, E.M., O’Connor, E., Smith, N. and Whitlock, E.P. 2016. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Jama. 315(23), pp.2576-2594.

- Zavoral, M., Suchanek, S., Zavada, F., Dusek, L., Muzik, J., Seifert, B. and Fric, P. 2009. Colorectal cancer screening in Europe. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 15(47), p.5907.

- Shaukat, A. and Levin, T.R. 2022. Current and future colorectal cancer screening strategies. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 19(8), pp.521-531.

- Anacleto, C., Rossi, B., Lopes, A., Soares, F.A., Rocha, J.C.C., Caballero, O., Camargo, A.A., Simpson, A.J. and Pena, S.D. 2005. Development and application of a multiplex PCR procedure for the detection of DNA methylation in colorectal cancer. Oncology reports. 13(2), pp.325-328.

- Fang, Y., Peng, J., Li, Z., Jiang, R., Lin, Y., Shi, Y., Sun, J., Zhuo, D., Ou, Q., Chen, J. and Wang, X., 2022. Identification of multi-omic biomarkers from fecal DNA for improved detection of colorectal cancer and precancerous lesions. medRxiv. pp.2022-11.

- Raut, J.R., Guan, Z., Schrotz-King, P. and Brenner, H. 2020. Fecal DNA methylation markers for detecting stages of colorectal cancer and its precursors: a systematic review. Clinical Epigenetics. 12(1), pp.1-19.

- Shivapurkar, N. and Gazdar, A.F., 2010. DNA methylation-based biomarkers in non-invasive cancer screening. Current molecular medicine. 10(2), pp.123-132.

- Carethers, J.M. 2020. Fecal DNA testing for colorectal cancer screening. Annual Review of Medicine. 71, pp.59-69.