Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia worldwide (60-70% of all dementia cases) and is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder. Though around 10-15% of cases are genetic, the vast majority of cases are sporadic and attributed to many risk factors. There is, at present, no cure or disease-modifying treatments for Alzheimer’s disease.

Image Credit: Naeblys / Shutterstock

Key Symptoms: Initially mild cognitive impairment and subtle memory loss of recent events before progressing to more severe cognitive impairment with profound amnesia, in addition to personality, behavioural and motor changes, which ultimately lead to death.

Prevalence: Currently 50 million people worldwide have dementia, and of all dementia cases, 6 in 10 have Alzheimer’s – 5.8 million in the US and 850,000 in the UK (as of 2018).

Onset & Prognosis: Usually over the age of 65, with death occurring 3-9 years after onset.

Skip to:

What is Alzheimer’s Disease?

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) accounts for around 60% of all dementia cases worldwide, making it the most common form of dementia. Alzheimer’s is a progressive neurodegenerative disease with symptoms gradually worsening over a period of a few years. As with most dementias, Alzheimer’s symptoms usually begin with subtle difficulties in remembering recent memories before gradually progressing to more severe symptoms (outlined below).

Alzheimer’s is generally a disease of advanced age and becomes more common over the age of 65. However, developing dementia is not a normal or healthy part of ageing. In rarer cases, Alzheimer’s can affect individuals much younger (between 30-40 years old) with approximately 5% of cases occurring in people under the age of 65. Though the disease is the same, the causes of early-onset Alzheimer’s are usually slightly different to what is known as sporadic Alzheimer’s disease.

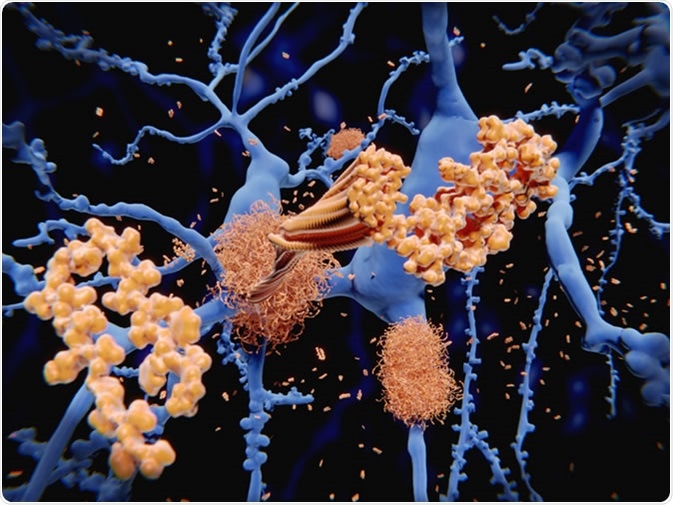

Irrespective of the exact cause of Alzheimer’s, which is still poorly understood, two key pathological hallmarks are key to Alzheimer’s: amyloid plaques and tangles (discussed in detail later). Over time, these abnormal proteins contribute to the death of neurons leading to a generalised shrinkage of the brain (cortical atrophy), which leads to the symptoms of Alzheimer’s, as well as death within 9 years after symptoms start.

Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid-beta peptide accumulates to amyloid fibrils that build up dense amyloid plaques. 3d rendering - Image Credit: Juan Gaertner / Shutterstock

Alzheimer’s Disease Signs & Symptoms

As Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disease, symptoms are initially subtle and mild, before gradually worsening over a period of several years. The onset, progression severity and speed, as well as time to death varies significantly between affected individuals, depending on the exact cause and mechanism involved.

The symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease can be broken down into three stages:

1. Early-Stage Symptoms:

- Subtle memory loss of the most recent events e.g. forgetting a recent conversation or event, as well as repetitive questioning and the inability to select certain words in conversations

- Subtle mood changes or behavioural changes which are not normal for the individual – these can manifest as increased anxiety and confusion

- Other cognitive symptoms may include increased difficulty in making decisions and becoming more hesitant in certain things

It is important to note that misplacing items or forgetting things occasionally is a normal part of ageing – however, when this becomes routine, is often a sign of dementia.

2. Middle-Stage Symptoms:

- Worsening of memory loss which progresses to forgetting names of people close to them, as well as forgetting the faces of loved ones

- Mood changes become more profound with increased anxiousness, frustration and signs of repetitive or impulsive behaviours

- Depressive symptoms alongside anxiety – including loss of motivation

- In some cases, there may be signs of delusions and hallucinations

- Insomnia and disturbed sleep patterns are common

- The emergence of motor difficulties including aphasia (speech problems)

At this stage, activities of daily living become impaired and patients usually require some level of care and assistance, especially as the disease progresses.

3. Late-Stage Symptoms:

- All of the above symptoms become more severe, behavioural, mood, motor and cognitive – with increased distress for both the patient and caregiver

- Violence towards caregivers is not uncommon and patients can become suspicious of those around them, including loved ones

- Due to feeding issues, severe weight loss can occur in some patients

- As motor problems worsen, there may be severely impaired speech, difficulty in positioning oneself, urinary and bowel incontinence

At this stage, activities of daily living become severely impaired and patients usually require full-time care and assistance. Patients become more withdrawn from life and symptoms decline eventually leading to death.

In a lot of cases, the progression of disease course can be enhanced by other factors independent of Alzheimer’s pathology. These include infections, strokes, head injuries and delirium. Sometimes, certain medications can also worsen the symptoms of dementia. In general, death occurs anywhere from 3-9 years after the first symptoms appear.

There is much overlap between symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. It is also common for patients with Alzheimer’s over the age of 65 to also experience symptoms and pathology of vascular dementia, which often initially manifests with more marked motor impairment.

New definition of Alzheimer’s changes how disease is researched

Causes of Alzheimer’s Disease

The exact cause of the majority of Alzheimer’s cases (sporadic) is still not fully known, however, around 5-10% of all cases are due to genetic differences, which are now well characterised.

Genetics

5-10% of all cases are what is termed familial Alzheimer’s disease, and are due to inherited genetic mutations to key genes. Less than 1% of all cases of Alzheimer’s are due to autosomal dominant inheritance and its associated early-onset Alzheimer’s before the age of 65 (rare).

There are three key deterministic genes (directly causative) associated with genetic forms of Alzheimer’s: APP, PSEN1 & PSEN2. These genes are all involved in amyloid processing and the production of beta-amyloid plaques, the main pathological hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.

Therefore, having a family history of dementia may suggest that specific genetic mutations may exist in the gene pool of the family, and that you may have an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s. Genetic screening and genetic counselling may be offered if this is the case.

There are several risk factor genes that have been associated with but not proven causative of Alzheimer’s. The most common of these genes is the APOE4 allele (form of APOE gene) that increases the risk of developing Alzheimer’s by 3-15 times depending on the inheritance of APOE4 alleles. It is estimated that around 60% of all people with Alzheimer’s have at least one APOE4 allele. Having APOE4 alleles in combination with other deterministic genes, or other risk factors (outlined below) may exacerbate disease severity and progression.

Other implicated genes include autosomal dominant mutations to ABCA7 and SORL1. Allelic variations of TREM2 (microglia implicated) are also thought to confer up to a 3 times higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. There are many polymorphisms (subtle genetic changes; SNPs) in up to 20 other genes that are associated with an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

Risk Factors (Protective & Destructive)

Aside from genetic causes of Alzheimer’s disease, the exact mechanism of how Alzheimer’s develops is still poorly understood, though there are several key risk factors involved.

Factors associated with increased Alzheimer’s risk:

- Advancing age – 1 in 6 people over the age of 80 have dementia, and the risk of developing Alzheimer’s doubles every 5 years after 65.

- Head injuries – There is an association with severe head injuries and the development of Alzheimer’s. Furthermore, having head injuries when dementia is present can actually worsen the symptoms and prognosis.

- Cardiovascular disease – Lifestyle factors that are associated with heart disease such as diabetes, high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol levels, smoking and obesity are also all associated with an increased risk of both vascular dementia (primarily) as well as Alzheimer’s.

- Down’s syndrome – The genetic basis for Down’s syndrome (trisomy 21) which has a 3rd copy of chromosome 21, also carries an extra copy of the APP gene which produces beta-amyloid. Having an extra copy of the APP gene leads to a 50% increase in amyloid is production over normal levels. Therefore, persons with Down’s syndrome are at higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

- Other common risk factors that may contribute to developing Alzheimer’s also include having a sedentary lifestyle, hearing loss, stress and untreated depression.

- A single study has also shown an association between calcium supplementation and Alzheimer’s disease, but only among older women who have a history of stroke https://www.news-medical.net/health/Alzheimere28099s-Disease-and-Calcium-Supplements.aspx

As previously mentioned, in the vast majority of cases, dementia is not a normal part of ageing, and you can actively minimise your risk of developing Alzheimer’s and other dementias. Many active lifestyle changes can reduce your risk. These include:

- Reducing your risk of getting cardiovascular disease – stopping smoking, having an active non-sedentary lifestyle, losing weight if you are overweight, eating a healthy balanced diet with fresh fruit and vegetables as well as drinking less alcohol.

- If you have diabetes, keep on top of your medication and make active lifestyle changes such as managing you blood pressure and blood sugar levels.

- Keeping yourself mentally active – even something as simple as reading, doing crosswords or playing Sudoku.

- Brain training games have a beneficial short-term effect in improving cognition

- Loneliness and social isolation can also increase your risk of dementia, therefore volunteering in local communities or doing group sports is beneficial.

Brain Changes in Alzheimer’s Disease

There are two key pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s: beta-amyloid plaques, which form within brain tissue and around vessels (cerebral amyloid angiopathy) and tangles within neurons of a protein called tau. Together, these contribute to the neurodegeneration (death of neurons and synaptic connections) which leads to the overall shrinkage (atrophy) of brain matter within the cortex and hippocampus. The death of neurons and atrophy of key brain regions correlates with disease progression and symptom severity.

There are many symptomatic and pathological overlaps among the types of dementias. Lewy bodies of alpha-synuclein (the key protein involved in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy Bodies) can also sometimes be found in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. There may also be the build-up of fatty plaques (atherosclerosis) within the vessels of the brain which cause vascular dementia and stroke. There may also be the presence of TDP-43 (key motor-neuron disease protein) in the brain of Alzheimer’s patients. The combination of two or more dementias together is called mixed dementia, and the most common mixed dementia is Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.

It is now known that up to one-third of all supposed Alzheimer’s cases over the age of 85 might actually not be Alzheimer’s at all. A newly identified form of dementia, called limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy or LATE, produces symptoms that are nearly identical to those of AD in older persons, but are caused by the TDP-43 protein rather than amyloid. This discovery has major implications for correct diagnosis, treatment strategies, prognosis, and for scientists researching mechanisms and treatments for Alzheimer’s.

What You Can Do to Prevent Alzheimer's | Lisa Genova | TED

Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis

Short-term memory loss or subtle, early symptoms of dementia may be overlooked or attributed to medications, stress, depression and anxiety, which can mimic AD. However, if these symptoms gradually worsen and persist, then that may be a sign of dementia.

Unfortunately, there is no single test for diagnosing Alzheimer’s or any other dementia. If your GP is concerned that the symptoms may be due to dementia, they may refer you to a specialist – usually a neurologist and/or psychiatrist at a dedicated memory clinic. A neurologist will assess for physical signs of dementia, whereas a psychiatrist will evaluate the cognitive symptoms. A neurologist may also recommend a CT or MRI scan of the brain to assess any brain pathology to rule-out or confirm diagnosis.

At the memory clinic, a standardised questionnaire called the mini mental state examination (MMSE) is used to assess cognitive ability. This is a set of 30 questions, in which a score greater than 24 indicates normal cognitive abilities. Mild cognitive impairment is usually considered between 19-23 points, moderate cognitive impairment between 10-18 points, and severe cognitive impairment at 9 points or lower. However, these scores need to be adjusted for educational attainment and age.

In combination with the MMSE, brain scans, and exclusion of other causes (e.g. by blood tests for medication interactions), a positive diagnosis can eventually be made. This can take some time due to the subtlety of early symptoms. However, as the disease progresses, diagnosis may become easier.

Treatment Strategies & Prognosis for Alzheimer’s Disease

There is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease at present, nor are there any major disease modifying therapies. However, there are various medications can temporarily improve symptoms.

Current Medications

- Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Inhibitors – the levels of a key neurotransmitter, acetylcholine, is thought to be reduced in Alzheimer’s disease. AChE inhibitors work to prevent the breakdown of acetylcholine, thus increasing the levels in the brain. These include rivastigmine and donepezil.

- Glutamate Inhibitors – such as memantine

- Antidepressants e.g. SSRIs and Antipsychotics e.g. risperidone

These medications only manage the condition by helping treat some of the symptoms; however, none of them treats the underlying causes and pathology. Underlying cardiovascular disease and its risk factors can be modified using medications for diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol (such as statins) and heart problems (such as aspirin).

Non-Medication Approaches

- Cognitive Rehabilitation – in conjunction with a trained therapist, as well as caregiver, personal goals such as performing everyday tasks can be slowly achieved

- Cognitive Stimulation – taking part in social/group activities that can help improve memory and problem-solving skills

- Reminiscence – actively talking about events from the past by using visual aids (e.g. photographs) and music. This can improve mood and wellbeing.

- Music from the past has also been shown to stimulate forgotten memories, as well as improve mood and behaviour (calming effect). It has also reduced social isolation and encourage social interaction and in the expression of feelings.

As with medications; which may be used in combination with non-medication approaches, symptoms are only transiently ameliorated, and the disease course will gradually worsen.

Alternative Treatments & Preventions

There are numerous alternative therapies that are thought to help patients with dementia, though evidence for the effectiveness is lacking. Some of these include:

The effectiveness of these supplements is not yet fully proven, but these supplements usually will not cause harm if used in moderation. As with most alternative medicines, the majority of large-scale studies do not seem to show any significant effects of such medicines on the positive treatment of health conditions. When considering alternative medicines, patients and caregivers should not forgo conventional medicines and therapies in favour of alternative medicines.

Current Clinical Trials

There are several notable clinical trials in progress that aim to study the effects of various treatments:

- Sargramostim – reduces the accumulation of beta-amyloid

- MK8931 – selective beta-secretase inhibitors (reduced production of amyloid)

- CAD106 – induces immunity to beta-amyloid without triggering an autoimmune response

- TRx0237 – inhibits the accumulation of tau

- Intranasal insulin – improvement of blood sugar control and insulin resistance in the brain

Whether these therapies are able to effectively modify disease course and improve symptoms significantly is yet to be seen.

Support for Individuals and Caregivers

Getting a dementia diagnosis can be a difficult and upsetting for the individual and close family and friends. However, there are many excellent organisations that offer support for patients and caregivers.

In the UK, there is Alzheimer’s Research UK & Alzheimer’s Society. In the US, there is the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America & Alzheimer’s Association. There are also international organisations such as Alzheimer’s Disease International. Their websites contain lots of information about accessing support services, as well as more information about the condition.

Sources

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/alzheimers-disease/

- Shabir et al, 2018. Neurovascular dysfunction in vascular dementia, Alzheimer's and atherosclerosis. BMC Neuroscience. 19:62. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30333009

- Pangman et al, 2000. An examination of psychometric properties of the mini-mental state examination and the standardized mini-mental state examination: implications for clinical practice. Appl Nurs Res. 13(4):209-13 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11078787

- www.brightfocus.org/.../clinical-trials-alzheimers-disease-whats-new

Further Reading

Last Updated: Oct 25, 2019