Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) is one of the most serious congenital heart anomalies, with an incidence of about 0.016-0.036% in North America, and has a mortality of 100% if untreated. Though it accounts for about 2-3% of all congenital heart diseases, it accounts for 23% of all infants who die from such causes.

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome - Image Copyright: Alila Medical Media / Shutterstock

Causes

HLHS is a rare condition among the congenital heart diseases. Its incidence is much higher among males as compared to females. While 1 in 10 of these babies has other heart anomalies as well, the cause of this syndrome is not known. Some genetic factors also predispose to the development of this syndrome, but they have not been identified as yet. 12% of infants with HLHS have other non-heart-related anomalies such as Holt-Oram or Turner syndromes.

Abnormal pathology in HLHS

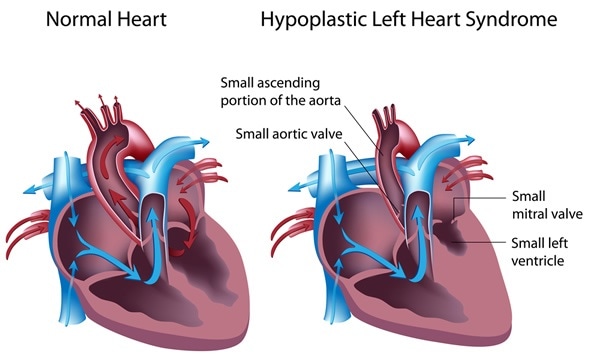

The lack of normal development of the left side of the heart includes:

- A small left ventricle

- Stenosed atrioventricular opening and a small or absent mitral valve

- A closed or small aortic outflow tract with a stenosed or abnormal aortic valve

- Coarctation of the aorta, found in up to 70% of these children

The normal heart has four chambers, namely:

- Two upper chambers called the left and the right atria, which receive venous blood from the lungs and the systemic veins respectively.

- Two lower pumping chambers called the left and the right ventricles, which receive blood from the atria and pump it to the systemic and the pulmonary circulation respectively.

Normally, the left and right sides of the heart are completely separated from each other. In infants with HLHS, the undeveloped left ventricle is unable to sustain its normal pumping function. In addition, the left atrioventricular opening and the mitral valve are usually stenosed or atretic.

The oxygenated blood reaching the left atrium through the pulmonary veins goes to the right atrium instead of to the left ventricle. The normal persistence of the foramen ovale, an opening in the septum separating the two atria, allows this interatrial communication to occur. At this level, therefore, venous deoxygenated blood in the right atrium mixes with the oxygenated blood reaching the left atrium from the lungs.

From the right atrium, the blood passes into the right ventricle which pumps it back to the lungs through the pulmonary trunk. During this circuit, therefore, the aorta is not involved in the pumping of blood. The only way in which oxygen-containing blood reaches the systemic circulation is via the patent ductus arteriosus, a blood vessel connecting the aorta and the pulmonary trunk in fetal life, which normally closes after birth.

In infants with HLHS, however, this ductus carries the blood pumped from the right ventricle into the pulmonary artery to the aorta, and is the only source of oxygen for the systemic circulation. Once the ductus closes, the body is deprived of blood flow and the baby develops acute symptoms, usually around the fourth or fifth day of life. Keeping the ductus arteriosus open is a primary medical goal, therefore, to keep the child alive.

What is hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS)?

Symptoms

The normal changes in blood flow that happen in the first few days of life cause infants with HLHS to become acutely ill as they are deprived of the compensatory shunt between the right and the left side of the heart. These include the increased blood flow to the lungs, the closure of the ductus arteriosus, and the closure of the atrial septal openings.

At the same time, the narrow aorta prevents blood from flowing back into the ascending part, which compromises coronary blood flow. Thus the perfusion of the heart and of the coronary vessels is reduced, leading to hypoxia, metabolic acidosis, and shock. Death usually occurs within 2 weeks in affected infants.

The symptoms with which they present occur within the first three days of life, typically after the first day. They include:

- Breathlessness

- Rapid shallow breathing

- Pounding heartbeat

- Weak pulse

- Mild cyanosis or a bluish-gray discoloration of the lips and around the mouth

- Signs of shock such as sweating and a cold, clammy skin

Severe cyanosis is uncommon.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 26, 2019