Mar 29 2019

Scientists once thought that mammals entered adulthood with all of the neurons they would ever have, but studies from the 60s found that new neurons are generated in certain parts of the adult brain and pioneering studies from the 90s helped identify their origins and function. In the latest update, a team of researchers has shown in mice that a single lineage of neural progenitors contributes to embryonic, early postnatal, and adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus, and that these cells are continuously generated throughout a lifetime. The study appears March 28 in the journal Cell.

Conceptually, this suggests that our brains have the capacity for continuous improvement, adaptation, and incorporation of new cells into the circuitry. This turns out to be very important, because the hippocampus is well known to be important for learning, memory, and mood regulation."

Senior author Hongjun Song of the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania

Neurogenesis was originally believed to have two phases: the developmental phase, which occurred mostly in embryos and immediately after birth and in which neurons are generated from a stem cell that build up circuitries of the full nervous system. Adult neurogenesis was thought to originate from a specialized population of neural stem cells that were "set aside" and distinct from the precursors generating neurons during embryogenesis. But it turns out it's not so straightforward.

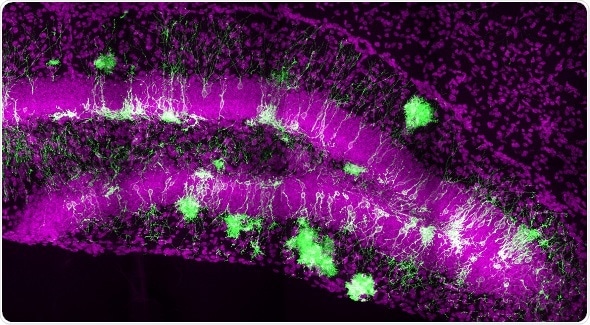

In the current study, the researchers labeled precursor neural stem cells in mice at a very early stage of brain development. They then followed the lineage of cells throughout development and into adulthood. Their findings revealed that new neural stem cells with the precursor cells' label were continuously generated throughout the animals' lifetimes.

RNA-seq and ATAC-seq analyses were used to confirm that all the cells in the lineage had a common molecular signature and the same developmental dynamics.

"Earlier studies have suggested that specific parts of the brain, such as the olfactory bulb and the hippocampus, can generate neurons," Song says. "Until this study, it wasn't clear how this happens. We've shown for the first time in a mammalian brain that development is ongoing from the beginning, and that this one process happens over a continuum that lasts a lifetime."

The prevalence of adult neurogenesis in humans and primates is an area of active discussion in the field and more research is needed to determine whether the process of stem cell generation observed in the mouse pertains to other mammals too. The investigators plan to study the processes of neurogenesis in more detail, to look for ways to potentially increase or preserve it, as well as to determine how it's regulated at the molecular level.

"This paper has implications for understanding how the brain maintains a 'young' state for learning and memory," says co-senior author Guo-li Ming, also of the Perelman School of Medicine. Additionally, "if we could harness this capacity and this mechanism, we may be able to repair and regenerate parts of the brain," she concludes.

Source: http://www.cellpress.com/