Introduction

Key Metabolic Pathways in Tumor–Immune Interactions

TME Competition

Therapeutic Implications

Emerging Technologies

Conclusions

References

Further Reading

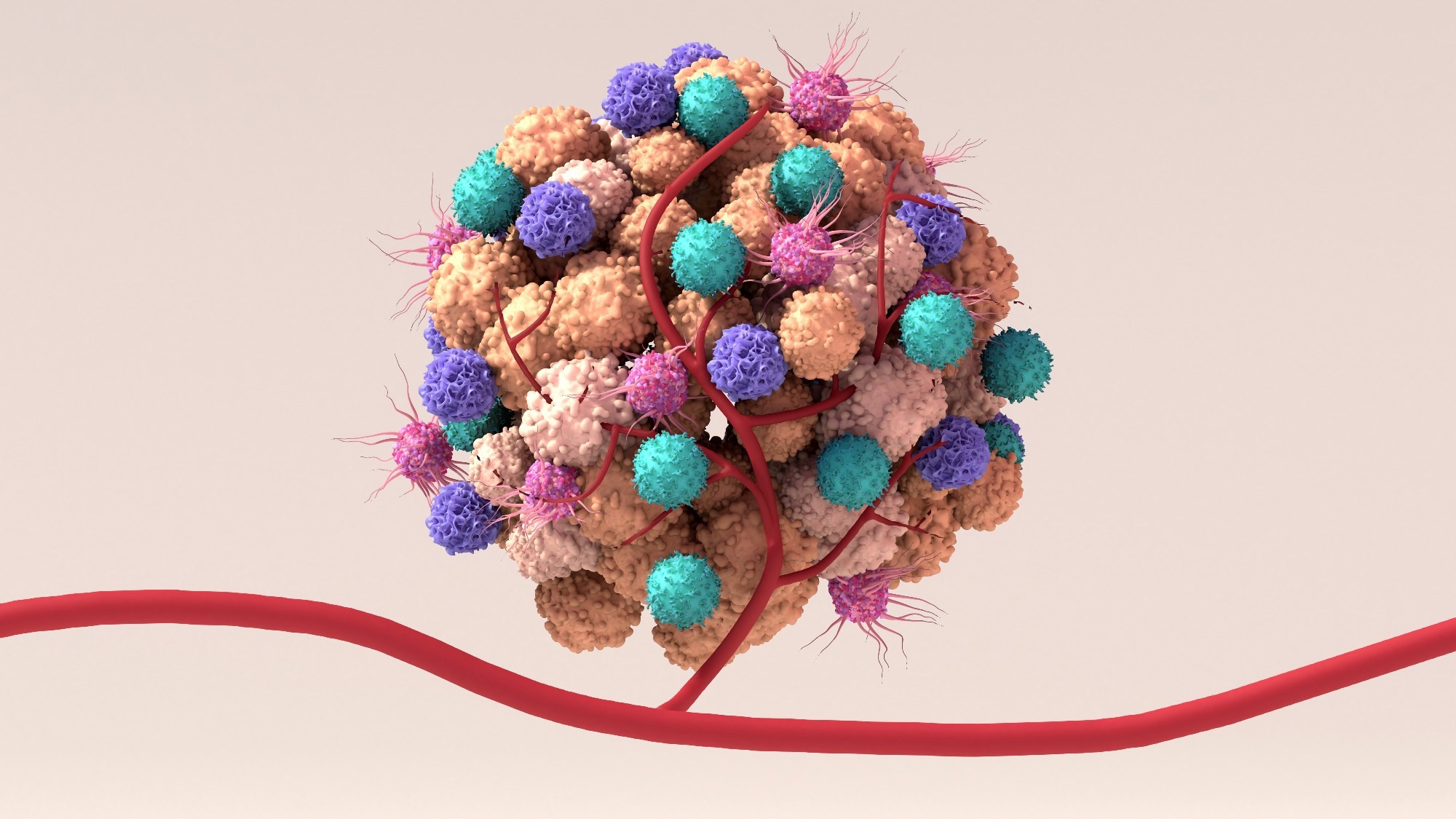

The article explores how metabolic reprogramming within the tumor microenvironment shapes immune cell function and resistance to therapy. It highlights therapeutic strategies that rewire cancer metabolism to restore antitumor immunity and enhance immunotherapy outcomes.

Image credit: Design_Cells/Shutterstock.com

Image credit: Design_Cells/Shutterstock.com

Introduction

Tumor growth unfolds within a tumor microenvironment (TME) defined by metabolic–immune crosstalk. Emerging evidence indicates that cancer cells not only reprogram glycolysis but also alter amino acid, lipid, and oxidative metabolism to evade immune surveillance. Cancer cells rewire glycolysis to meet adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and biosynthetic demands while altering the immune response.1

The Warburg effect elevates lactate, adenosine, and reactive oxygen species (ROS), reshaping the TME to promote immune evasion and exhaustion. Effector T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and dendritic cells (DCs) are suppressed as extracellular lactate acidifies niches and signals through receptors. Additionally, mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS accumulation further suppress effector cell metabolism.1

Nutrient competition for glucose and amino acids further starves lymphocytes, thereby weakening the function of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs). Tumor metabolism is not fuel; it is a program that suppresses antitumor immunity and steers outcomes.1

This article explains metabolic–immune crosstalk, how tumor metabolism suppresses immunity and drives resistance, and therapeutic tactics to rewire pathways and improve immunotherapy.

Aerobic glycolysis in tumors accelerates lactate production, lowering intratumoral pH and creating an acidic, hypoxic, nutrient-poor niche. This lactic acidosis impairs CTL migration and killing, reduces interferon-gamma output, and shifts the balance toward immunosuppressive Regulatory T cells (Tregs), producing a two-pronged brake on antitumor immunity. Lactate accumulation also stabilizes HIF-1α and induces vascular remodeling that limits immune cell infiltration. Targeting lactate handling or buffering acidity can help restore T-cell function.2

The tryptophan–kynurenine axis functions as a metabolic immune checkpoint. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) expressed by tumors depletes local tryptophan and accumulates kynurenine, driving T-cell proliferative arrest via the general control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2) stress kinase and increasing immune-checkpoint marker expression on tumor-infiltrating Cluster of Differentiation 8-positive T lymphocyte (CD8⁺ T) cells.

Kynurenine also acts through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) to enhance Treg differentiation and suppress effector signaling. Pharmacologic IDO1 blockade has synergized with checkpoint inhibitors and improved antitumor responses in preclinical and clinical studies.2

Lipid metabolism shapes T-cell fate in glucose-depleted tumors. CD8⁺ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes can sustain longevity by switching to fatty-acid oxidation (FAO) through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha (PPAR-α) signaling and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A (CPT1A).

However, excess long-chain fatty-acid uptake via cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36) promotes lipid peroxidation, ferroptosis, and loss of effector function. Meanwhile, Tregs preferentially rely on FAO, giving them a survival and functional advantage in the TME. Recent data highlight that inhibiting CD36 or enhancing mitochondrial FAO balance can rejuvenate exhausted T cells. These nodes, PPAR-driven FAO, CD36-mediated uptake, and Treg lipid reliance, offer levers to reprogram immunity.2

TME Competition

In the TME, cancer cells and lymphocytes compete for scarce nutrients, driving immune dysfunction. Limited glucose availability, together with lactate accumulation, impairs CTL proliferation and interferon-γ production, while forcing T cells to rewire toward fatty-acid use or acetate-supported histone acetylation just to maintain effector programs.

Similar competition extends to amino acids: glutamine supports T-cell activation, and depletion blunts effector differentiation; low l-arginine reduces oxidative phosphorylation and survival of T cells, favouring exhausted, less persistent phenotypes. Tumor cells further secrete immunosuppressive metabolites, such as adenosine and prostaglandin E₂, which compound nutrient stress–mediated suppression.3

Tumours also upregulate transporters and enzymes to capture these fuels, outcompeting nearby immune cells and tipping the niche toward immune suppression.3

Hypoxia is a parallel pressure that reshapes infiltration and function through hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α). In macrophages and other myeloid cells, tumour-derived lactate stabilizes HIF-1α, induces vascular endothelial growth factor, and drives a protumoural, M2 (alternatively activated) macrophage-like polarization that correlates with poor CD8+ T-cell and NK-cell entry. Conversely, pharmacologic HIF-1α modulation can normalize vessels and enhance immune access to tumor cores.3

Hypoxic tumour-associated macrophages show altered glycolysis and vessel-normalizing effects when this axis is perturbed, underscoring how oxygen tension and HIF-1α signalling pattern the immune landscape. Together, nutrient deprivation (glucose, arginine, glutamine) and hypoxia–HIF-1α signalling create a metabolically hostile TME that exhausts effector cells and restricts their infiltration, central barriers that metabolic and immunologic therapies now seek to reverse.3

Therapeutic Implications

Targeting tumor metabolism can relieve metabolic constraints on antitumor immunity and enhance the efficacy of checkpoint blockade. Inhibiting IDO1 reverses tryptophan depletion and kynurenine accumulation, thereby restoring CTL function and reducing the dominance of regulatory T cells. Blocking lactate flux with monocarboxylate transporter (MCT) inhibitors, such as AZD3965, or disrupting the CD147–MCT-1 axis lowers extracellular acidification, which otherwise suppresses T-cell cytokine production. Buffering the TME with oral bicarbonate or using proton-pump inhibitors can further normalize pH and improve effector function.

Clinical trials also explore glutamine antagonists and arginase inhibitors as adjuncts to reinvigorate T-cell metabolism. These maneuvers directly counter the hostile metabolic niche that fuels immune exhaustion.4

Metabolic adjuvants provide an additional lever for synergy. The mechanistic target of modulator rapamycin (mTOR) can bias T cells toward durable memory states that support sustained tumor control. At the same time, the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activator metformin enhances T-cell metabolic fitness and exerts immune-mediated antitumor effects. Metformin additionally reduces intratumoral hypoxia and lactate accumulation, indirectly enhancing checkpoint therapy.4

Layering these strategies with checkpoint inhibitors such as anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), anti-programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), or anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) can deepen and broaden responses by simultaneously relieving inhibitory signaling and removing metabolic roadblocks.

Emerging data suggest that patient selection using metabolic biomarkers (example, IDO1 expression, lactate burden) and thoughtful sequencing or co-dosing will be key to maximizing benefit while limiting toxicity, pointing to a future of rational, metabolism-informed immunotherapy combinations.4

Emerging Technologies

Emerging platforms now map tumor metabolism with cellular and spatial precision. Single-cell multi-omics integrates genome, epigenome, transcriptome, and proteome layers, sometimes in the same cells, to expose metabolic heterogeneity that shapes the TME.

Spatially resolved assays such as Spatial-Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by sequencing (Spatial-CITE-seq), high-definition Visium High Definition (Visium HD), and spatial transcriptomics–Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-combinations like Perturb-Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (Perturb-FISH) preserve tissue architecture, revealing immune–metabolic “neighborhoods” and exclusion zones linked to therapy response.

Integration of metabolomics with imaging mass cytometry is also enhancing real-time metabolic–immune landscape mapping. These tools move beyond bulk averages to chart metabolic niches across the TME and align them with immune phenotypes and evolutionary dynamics.5

CRISPR-coupled single-cell readouts are identifying new metabolic checkpoints. Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by sequencing (CITE-seq) and CRISPR pooled screening with single-cell ribonucleic acid (RNA) sequencing (CROP-seq) pair-pooled perturbations with transcriptomes to nominate enzymes and transporters that reprogram immunosuppressive metabolism.

Epigenome-focused screens, such as Perturb-Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin sequencing (Perturb-ATAC) and CRISPR–single-cell Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin sequencing (CRISPR-scATAC-seq), uncover chromatin circuits that gate metabolic switching and T-cell exhaustion.

Meanwhile, Expanded CRISPR-compatible CITE-seq (ECCITE-seq) adds protein and guide capture. New RNA-targeting CRISPR-associated protein 13 RNA Perturb-sequencing (Cas13 RNA Perturb-seq) broadens the target space to metabolic RNAs. Together, these CRISPR–single-cell modalities provide a discovery engine for lactate handling, amino-acid catabolism, and adenosine generation nodes that can be co-targeted with checkpoint blockade.5

Conclusions

Immunotherapy succeeds when we treat cancer not as a single target but as an ecosystem shaped by metabolism and immunity. The TME is governed by fuel competition, hypoxia, acidity, and lipid remodeling that drain effector programs and empower suppressive cells.

Durable responses will require joint strategies: relieving metabolic bottlenecks, normalizing pH and oxygen, reprogramming T-cell energetics, and aligning dosing and sequencing with checkpoint blockade.

Advances in single-cell and spatial metabolomics are now bridging metabolic signatures with patient outcomes, enabling precision metabolic–immune interventions.5 By integrating metabolic adjuvants, biomarkers, and rational combinations, we can convert hostile niches into habitats where immunity prevails consistently.

References

- Zhang, H., Fan, J., Kong, D., Sun, Y., Zhang, Q., Xiang, R., Lu, S., Yang, W., Feng, L. & Zhang, H. (2025). Immunometabolism: crosstalk with tumor metabolism and implications for cancer immunotherapy. Molecular Cancer. 24(1). 1-43. DOI:10.1186/s12943-025-02460-1, https://molecular-cancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12943-025-02460-1

- Ganjoo, S., Gupta, P., Corbali, H.I., Nanez, S., Riad, T.S., Duong, L.K., Barsoumian, H.B., Masrorpour, F., Jiang, H., Welsh, J.W. & Cortez, M. A. (2023). The role of tumor metabolism in modulating T-Cell activity and in optimizing immunotherapy. Frontiers in immunology. 14. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1172931, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1172931/full

- Elia, I., & Haigis, M. C. (2021). Metabolites and the tumour microenvironment: from cellular mechanisms to systemic metabolism. Nature metabolism. 3(1). 21-32. DOI:10.1038/s42255-020-00317-z, https://www.nature.com/articles/s42255-020-00317-z

- Kouidhi, S., Ben Ayed, F., & Benammar Elgaaied, A. (2018). Targeting tumor metabolism: a new challenge to improve immunotherapy. Frontiers in immunology. 9. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00353, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00353/full

- Le, J., Dian, Y., Zhao, D., Guo, Z., Luo, Z., Chen, X., Zeng, F. & Deng, G. (2025). Single-cell multi-omics in cancer immunotherapy: from tumor heterogeneity to personalized precision treatment. Molecular Cancer. 24(1). DOI:10.1186/s12943-025-02426-3, https://molecular-cancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12943-025-02426-3

Further Reading

Last Updated: Dec 22, 2025